Chapter contents

Chapter summary

There are three phases of setting up a specialised parent-infant relationship team: preparing for operational delivery, starting the parent-infant work and steady-state management.

This chapter covers the first phase, including information about things to do before you start accepting referrals such as:

- Creating referral pathways

- Clarifying step up, step down and step out relationships

- Establishing strategic and operational relationships across the system

- Marketing and promotion

Chapter 6 covers the second and third phases including operational information such as how to manage referrals and waiting lists, recording clinical notes, data management, establishing beginnings and endings with families, managing risks and safeguarding.

You can download this chapter as a PDF here, or simply scroll down to read on screen.

Developing a service within the local context

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams are found in the public sector, private sector and voluntary and community sectors. Invariably, they emerged from the passion and tenacity of a small group of committed individuals who had a vision and set out to achieve it. Hence, there is no one way to set up a team but in listening to their stories we have heard four repeated themes:

1. Start where you are with what you’ve got

The largest and best-sustained parent-infant relationship teams often started as one practitioner or commissioner carving out a small bit of time or money to do something differently. This might have been a psychologist offering consultation to multi-agency colleagues, a commissioner squeezing money out of their baseline to appoint a specialist health visitor, a committed community member pulling interested parties together or a child psychotherapist offering to do their sessions jointly with a children’s centre worker.

This was the start that exposed others to the evidence and impact of parent-infant work, upon which word of mouth and collective local campaigning was built. The exact details are varied and inspiring, but they frequently share these humble beginnings. (See the end of Chapter 3 Funding and Commissioning for more examples).

Leeds Infant Mental Health Service grew from a part-time psychology post in Sure Start in 2002. It is now a thriving team of clinical psychologists, health visitors and infant mental health practitioners. They have trained over 2500 local practitioners and offer training, consultation and supervision across the city.

2. Build a network: you can’t do this alone

Building a personal and professional supportive network, and raising awareness across agencies and sectors, can help strengthen your resolve, unify the system around a common agenda and create a collective voice. Finding ways to have conversations, communicate evidence, and offer training to all stakeholders, including local families, MPs, councillors, commissioners and the families’ workforce are often important mechanisms.

A commissioner we know to be particularly passionate about parent-infant teams started her journey knowing nothing about the importance of babies’ emotional wellbeing. When she arrived in post, every service in her portfolio from CAMHS to health visiting to paediatrics, referenced the importance of the first 1001 days. A community of commitment had emerged from various local and national campaigns and awareness raising and had converged on the same point. It spurred the commissioner into wanting to find out more. Her motivation at first was based on the economics of prevention but when she read the science and research in greater depth, she was fully persuaded of the case for change. She pulled together the committed band of practitioners who had been working ardently for years to raise awareness, and a broad group of stakeholders, and together they launched a specialised parent-infant relationship team.

3. Create clear and concise but varied arguments

The case for specialised parent-infant teams is compelling but funders and commissioners hear compelling stories multiple times a day. Passion is not enough: decisions to commission services are based on well-written arguments which cater to the needs of multiple diverse audiences.

What appeals to a public health commissioner responsible for the 0-2s strategy might be different from what appeals to a grant giving foundation, the Police and Crime Commissioner, Director of Children’s Services or the Clinical Commissioning Group responsible for CAMHS. Your arguments can sit alongside a pitch which puts the experience of babies in crisis at the heart of the message and describes how their distress is communicated. See Chapter 2 The Case for Change for information about communicating evidence to commissioners.

4. Tenacity, taking chances and patience

Repeatedly, we hear about the tenacity of those early local pioneers and their patience in building a network, raising awareness and local campaigning. Many fledgling parent-infant teams face moments of jeopardy during their journey to becoming high-quality, sustainable services.

Taking risks and seizing opportunities are often a feature: going out on a limb to contact others, offer training or have conversations, recruit new staff or influence new strategies.

There is no other period in life which touches so many different services and professional groups and including them all in the development of a specialised parent-infant relationship service is helpful.

Pauline Lee, Clinical Lead, Tameside and Glossop Early Attachment Service

Different operating contexts

In Chapter 3, we described the various options for commissioning and funding. The information below about setting up a team is applicable to all commissioning and funding contexts although language, structural arrangements and exact operational details will vary across public, voluntary and private sectors. These differences are not to be underestimated so, where practical, we have described some of the variations and how to approach them.

Preparing for operational delivery

Setting up a new team requires lots of different activities to proceed in parallel. We advise teams to appoint an operational lead early, with dedicated time to drive forward the project plan.

This person ideally has experience of business development or project management so that they can initiate recruitment processes, secure appropriate clinical venues, and ensure business critical procedures and policies are in place in time.

We estimate that setting up a new team requires a 0.5-0.7 WTE project manager or operational lead for a minimum of nine months prior to accepting referrals, and this is borne out in recent experience of setting up a team in south east England.

Learning from existing teams shows that agreeing a ‘piloting’ period with stakeholders can be useful. This provides time to embed new working practices and establish good referral pathways before the service starts to be formally evaluated. Without this, early data can be skewed by common implementation challenges.

The overall aims of the team

Clarifying your overall aims and your Theories of Change will guide you in how to prepare for operational delivery. Co-creating a system-level (see Chapter 3 Funding and Commissioning) and a clinical-level (see Chapter 4 Clinical Interventions and Evidence-informed Practice) Theory of Change is a crucial starting point; if you don’t know where you’re going it’s much harder to get there.

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams have several inter-related objectives, which can be used to create a project plan.

| Objective | Project Planning | Resources |

|---|---|---|

Work with others (ideally including parents) to develop a joint strategic vision for infant mental health across the local health, social care and early years ecosystem In addition to direct therapeutic services to families, this should include the provision of training and consultancy to the local workforce, which might start with early years but needs to extend to all services including Adult Mental Health Co-create Theories of Change Establish a co-ordinated approach to funding and fundraising across relevant local strategic partners | Establish a strategic board to oversee development across the system and to ensure the inclusion of the parent-infant relationship in all strategic plans and documentation Clarify the forum for strategic fundraising co-ordination Agree a training, consultancy and direct delivery plan across all partners and aligned to local workforce development initiatives (eg safeguarding partnership training plans) Agree free at the point of delivery vs paid for arrangements Consider the need for an operational steering group with clear and robust reporting lines to senior managers and commissioners | Terms of reference for strategic and operational boards Examples of strategic plans which have included parent-infant relationships See ‘Agreeing a training, consultation and delivery plan’ below Examples of risk management policy |

Establish a clinical base for the team | Agree funding and maintenance responsibilities Ensure accessibility measures are in place for parents facing additional barriers | |

Agree: How client data will be captured and linked (where numerous funders/partners involved) How data about drop-ins, supervision, trainings will be captured | Agree data sharing protocols and reporting lines, including the management of risk where there is more than one delivery partner Work with in-house IT colleagues to ensure required data fields are embedded in local system Note: video feedback interventions seem universally to face difficulties with information governance and this particular point is likely to take time to resolve locally (please contact us for example policies) | Example of data handling and sharing protocol |

Ensure appropriate targeting and accessibility of services to support the parent-infant relationship by creating integrated pathways of care. Embed services within local facilities such as Children’s Centres, midwifery or GP clinics, community hubs, etc., wherever possible, to provide access routes which have high acceptability to families | Establish eligibility criteria, referral and discharge processes as part of broader Standard Operating Procedures Establish operational relationships with a range of referrers, community support organisations and relevant services | Stakeholder engagement plan Referral guidance for Perinatal Mental Health colleagues Examples of referral guidance and standard operating procedures Service specifications |

Use evidence-based tools to assess the parent-infant relationship, the infant’s social and emotional development, and the parent’s state levels of anxiety and depression, and use this information to guide any necessary intervention Deliver evidence- and practice-informed therapeutic interventions designed to strengthen the relationship between the parent(s) and their baby | Plan clinical interventions, including selection of engagement and assessment tools, therapeutic approaches and training/consultancy offer Dependent upon which interventions are going to be delivered, consider the intervention-specific training and supervision needs of particular tools and therapies, and plan to embed practice Purchase equipment (may include video cameras or tablets with video recording functions, baby change mats etc) | You will find information in Chapter 4 Clinical Interventions and Evidence-informed Practice |

Encourage and facilitate continuous professional development for all parent-infant therapists, by ensuring access to regular reflective specialist infant mental health supervision and training. (See Chapter 7 for recruitment, supervision and training information) | Plan for the supervision, continuing professional development and continuing professional registration needs of qualified staff Create a supervision policy | Chapter 7 Recruiting, Managing and Supervision contains information about the needs of qualified staff Example of supervision policy |

Support referred families to access relevant statutory and voluntary services, which could help to reduce any stress or adversity and/or provide practical and social support | Establish step up, step down and step out pathways to ensure families are safe and supported. Include the voluntary sector and the local infrastructure organisation (eg CVS) | |

Use recognised clinical outcome measures as a core part of service delivery – both to use clinically to support improvements in the relationship and to provide evidence of impact for service funders | Agree outcome measurement and information reporting requirements/schedule with commissioners and managers | See Chapter 8 Managing Data and Measuring Outcomes for further information about measuring outcomes |

Create safe and sustainable working practices which enable the team to deliver highly-skilled and emotionally demanding work | Collate/write policies and procedures including consent processes | Examples of: consent to service, consent to outcome measures, consent to share information with others, home working and lone worker policies, safeguarding management, adult mental health risk management, vulnerable adults’ policies, whistleblowing |

Promoting the work of the team at a local political, policy, stakeholder and commissioning level as a crucial part of the early years offer in each locality | Create a communication, marketing and influencing plan Liaise with partner communications teams | |

Engage with commissioners to ensure a two-way flow of communication, including data, which can help support the sustainability and reach of the service | Establish data management systems to support required reporting | Chapter 8 Managing Data and Measuring Outcomes contains more information about managing data |

Work as part of the ParentInfant Network co-ordinated and supported by the Parent-Infant Foundation, to contribute to a national collective voice which lobbies for the needs of babies and their families | Make links with the Parent-Infant Foundation to seek support and advice and join the Parent-Infant Network | Parent-Infant Foundation website |

Establishing a strategic board

Parent-infant relationship teams benefit from strategic connectedness and oversight. The function of a strategic board is to:

- Provide leadership in developing a joint strategic vision for babies’ emotional wellbeing across the local health, social care and early years ecosystem

- Ensure co-ordination and strategic fit of the team’s plans for training and consultancy to the local early years’ workforce

- Remove inter-agency barriers to the effective functioning of the team

- Ensure a shared vision across commissioning and delivery

- Set aspirational goals for the development of the team

Example terms of reference are available in the Parent-Infant Foundation website’s Network area.

Where parent-infant teams are smaller charities or Community Interest Companies (CICs), trustees can fulfil some of these functions and the local voluntary sector infrastructure organisation (eg CVS) can often support and guide you regarding the local strategic fora. Where teams are located within larger local charities or voluntary sector consortia, the host organisation is often already invited to be part of local strategic relationships. In the public sector, teams report to senior managers through their usual lines of accountability and that will often link them in to a multi-agency strategic forum.

All of these arrangements provide some opportunity to communicate with decision makers but their ability to service the strategic needs of parent-infant teams varies. Babies and their parents are frequently overlooked so we advocate for parent-infant relationship teams to report into either a dedicated board of their own or an existing one which is very closely connected to the first 1001 days agenda.

The Rare Jewels report identified a lack of co-ordination at a national level, and this can be replicated at a local level with stakeholders spread across safeguarding, public health, the voluntary and community sector, health, policing, education, social care, communities and the private sector. Ideally, all relevant partners are represented at the strategic board, but as a minimum it should include health visiting, midwifery, early help/children’s centres, children’s social care, perinatal mental health specialist teams and CAMHS.

Depending on the exact nature of the strategic board, they may also decide to appoint an operational steering group who will accept delegated responsibility for operational oversight and performance management of the development process. This is typical where the strategic board oversees more than one project, service or priority.

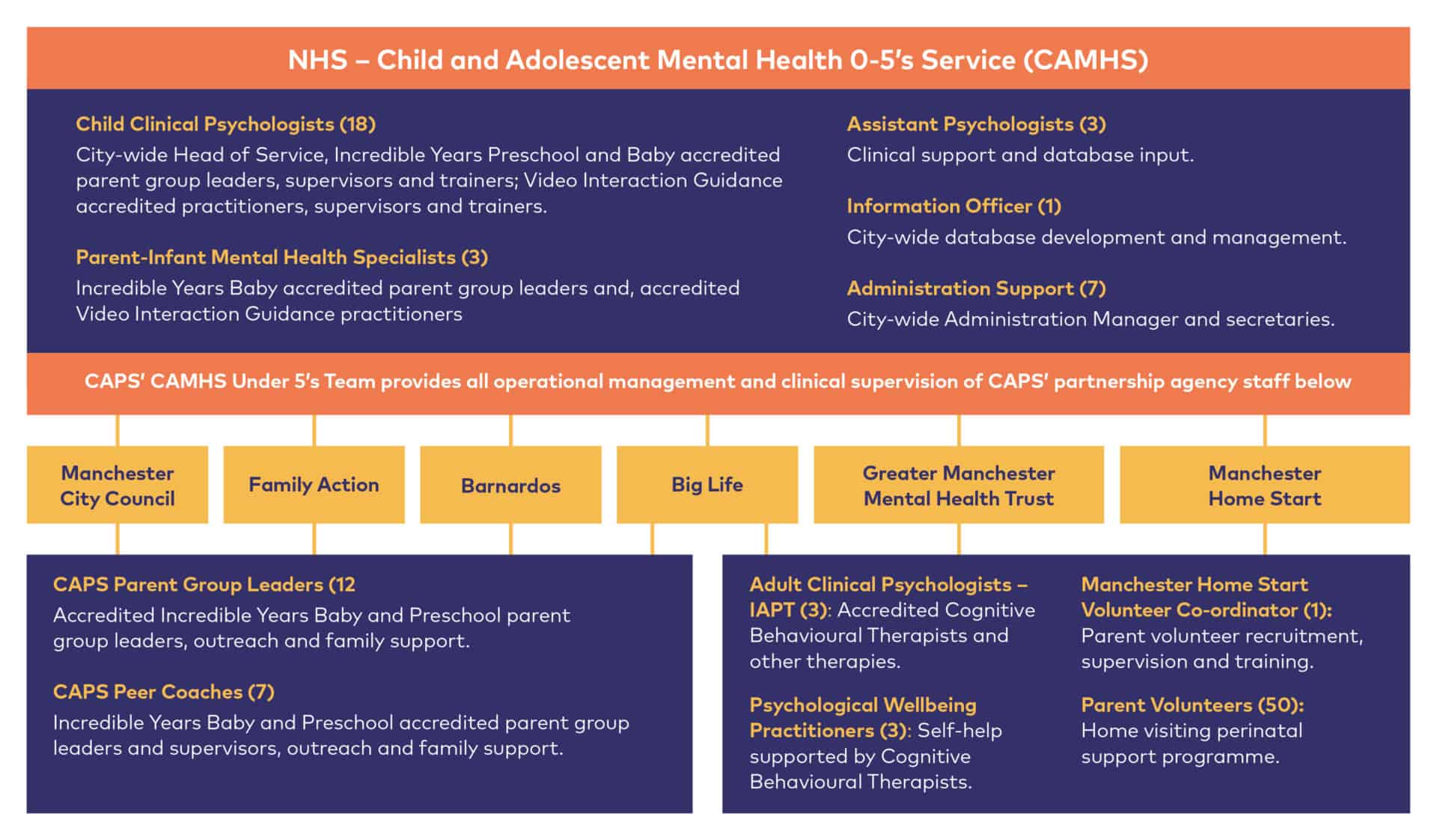

The diagram below shows how statutory and third sector partners work together in relation to the Child and Parent Service (CAPS) in Manchester.

Agreeing a training, consultation and direct delivery plan across all partners

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams sit at the heart of the ecosystem around babies’ emotional wellbeing. Their role is to be expert advisors and champions for parent-infant relationships. They use their expertise to help the local workforce to understand and support parent-infant relationships, to identify issues where they occur and take the appropriate action. This happens through offering training, consultation and/or supervision to other professionals and advice to system leaders and commissioners.

Workforce training should be planned at a strategic level, including voluntary sector partners, to maximise opportunities for partnership working, reduce duplication and ensure staff are released to attend. Training can be offered at different levels, for example light touch awareness raising (which may be part of other existing training), more detailed understanding for frontline helping professionals, and then in-depth skills training for those practitioners working with families in need of longer term or additional help.

This training activity may need to be funded separately from the contracted direct work of the team as it can be a substantial endeavour. Some areas make training about the emotional wellbeing of babies mandatory, in which case a whole workforce plan is required, to include an ongoing diary of dates to capture new starters. This often requires dedicated time from a training co-ordinator and/or administrator.

ABCPiP in Ballygowan, Northern Ireland are clear about their dual role to effect system-wide change and to deliver direct interventions to families. To that end, they have facilitated workforce training for over 350 local staff in various approaches such as Five to Thrive, Baby Massage and Baby Yoga and the Community Resilience Model.

All the trainings were delivered by expert external trainers and ABCPiP employed an Infant Mental Health (IMH) Keyworker to support practice embedding in all the approaches, to ensure the learning wasn’t lost.

The IMH Keyworker also continues to build relationships and support colleagues across the workforce to ensure parent-infant relationships are at the heart of local services and to maintain the profile of the ABCPiP team.

Information about some approaches to training and consultation are in Chapter 4 Clinical interventions and Evidence-informed Practice.

Free at the point of delivery and paid for arrangements

Most public sector specialised parent-infant relationship teams do not charge families for any of their services, but some charge for training or supervision. It is possible for NHS teams to charge families but this requires substantial development and administration and is likely to require Executive Board sign-off.

Some charities or CICs do charge families and this may be on a flat-rate or means-tested basis. Charities may charge for services (therapy, consultation or training) or use of their facilities but it is a legal requirement that they are not run in a manner which excludes families living in poverty.

For more information on this see Annex C Charging for Services in Public Benefit: rules for charities [1]

Agreeing data sharing and protocols

Where more than one organisation is involved in commissioning or delivery a specialised parent-infant relationship team, data often needs to be passed across organisational boundaries. This might be evaluation data, outputs data or demographic indicators.

We advise specialised parent-infant relationship teams to seek out existing data sharing protocols which exist locally between the same or similar partners and use these as a template or to inform their own. There will often be local intelligence and learning about how to make the process of data sharing easier.

Where personally-identifiable data is being shared, partners may need a legal contract to be drawn up, so ample time is needed in the project plan. This might occur for example where a parent-infant team requests a child’s developmental assessment from local health visitors to support outcome evaluation.

Agreeing how risk will be managed

As with any complex project, the setting up of a parent-infant relationship team involves different kinds of risk.

Clinical risks, such as safeguarding or adult mental health risks, should be managed according to existing local protocols, and parent-infant teams could request training from their local safeguarding, perinatal mental health and/or adult mental health colleagues to ensure they understand local procedures.

Where staff from different agencies will work together, for example a parent-infant therapist and a children’s centre worker running a Mellow Parenting group together, there should be a written policy about how safeguarding concerns will be responded to, handled, recorded and supervised, to clarify individual responsibilities and what will happen if colleagues have different views on the risk.

Project risks, such as not being able to recruit key staff or secure appropriate clinical venues, would normally be collated on a risk register so that the operational lead can discuss with the strategic board what needs to be done.

Unlike other mental health services there does not need to be a clinical diagnosis in the adult or child, and the client may be conceptualised as ‘the relationship’.

Eligibility or referral criteria

Eligibility criteria should reflect what the team has been commissioned to deliver, ensuring that the most appropriate families receive the service. Some teams adopt relatively broad eligibility criteria, accepting referrals from any source so long as the focus of referral is the parent-infant relationship.

Other teams are commissioned for families experiencing particular challenges, such as young parents in the looked after system, and some teams have a mix of these arrangements.

In 2019, a consistent message from parent-infant teams of all arrangements is that referrals have been getting more complex and concerning. If there are no robust internal mechanisms to manage different levels of need, practitioners get rapidly pulled into responding to the needs of the most complex family situations.

For example, where teams are commissioned to support families with a range of difficulties, clinicians spend most of their time helping the families with the most complex needs and far less time proportionally helping those with moderate needs. This may reflect what is required by commissioning contracts but can lead to misunderstanding with commissioners who have different expectations for preventative work.

Some families need an alternative type of support to “stabilise” their situation and resolve current crises before they are able to make use of a therapeutic offer, or for family support to work alongside the parent-infant therapist so that ongoing support needs do not undermine the family’s ability to focus on the parent-infant relationship.

Unlike other mental health services, in parent-infant relationship teams there does not need to be a clinical diagnosis in the adult or child, and the client may be conceptualised as ‘the relationship’. A request for service may be based on multiple risks to the parent-infant relationship which create a cumulative negative concern, and not necessarily on a single presenting problem or symptom in either parent or child. This allows a team to operate as a preventative and trauma-informed intervention, providing treatment where an infant has been exposed to potentially traumatising events and working to prevent any trauma in the future.

There are several risk factor tools available which provide the starting point for a referral to a parent-infant relationship team. The infant mental health team in Gloucestershire has developed a list of risk factors and stresses on the relationship which we have included in Chapter 4 Clinical Interventions and Evidence Informed Practice. Many of the specialised teams find it helpful in guiding referrers. See the Psychosocial and Environmental Stressor Checklist [2] for a more extensive example recommended by Zero to Three in the USA. These tools, which provide an initial method for acknowledging both the stressors that might be negatively impacting the parent-baby relationship as well as some potential risks, can help guide both referral criteria and referrers.

Perinatal mental health difficulties are commonly not considered to be an automatic reason for referral unless there is some evidence that the parent-infant relationship is under strain. Many mothers and fathers with perinatal mental health difficulties maintain good attunement with their baby, although it is a potential risk factor. Where a parent is experiencing mental health problems, parent-infant teams will usually want further information about the parent-infant relationship before accepting a referral.

It may be a clinical judgement as to whether a parental mental health problem needs to be addressed by adult mental health services before a referral with the baby will be considered. Some teams ask that a parent’s mental health is stabilised before referral for parent-infant work, so that the adult mental health issues and any associated risks do not hinder the relationship-focussed work.

A specialised parent-infant relationship team may not be suitable for the following situations:

- If a parent referred to a parent-infant relationship team is identified to have a new or unsupported episode of severe mental illness, they should be referred for a mental health assessment preferably (where available) from a specialist perinatal mental health service. This includes parents who are experiencing an active episode of a psychotic illness or those who are acutely suicidal and require active risk management.

- Parents with a substance dependence (including alcohol) where the situation is not being managed by the area’s specialist service. In such instances, liaison and joint working might first be set up to ensure the family’s lifestyle and capacity to place their baby’s needs before their own improves and then continues to be separately supported.

- A family where care proceedings, and any associated parenting assessments, are either imminent or ongoing. If these have been completed and the decision is that the baby remains in the family then it might be appropriate for a parent-infant relationship team to offer intervention.

Teams vary about accepting referrals with current safeguarding risks. Some teams accept referrals irrespective of whether the child is on a Child Protection Plan (CPP), some do but ask children’s services not to close the case until the parent-infant work is complete, some don’t accept referrals whilst the child is on a CPP.

It is helpful to co-produce draft referral guidance with commissioners and referring organisations, with the caveat that it may change, before you begin to promote your team to referrers and local services. Referral guidance is often adjusted within the first year of operational delivery in light of early learning about the needs and referral patterns of the local area.

There are examples of referral criteria in the Network area of the Parent-Infant Foundation’s website. If you have capacity to do so, offering some dialogue, introductory training or awareness raising sessions to referrers can help improve the appropriateness and rate of referrals.

Setting up referral pathways

Referral or recommendation to a specialised parent-infant relationship team should not be seen in isolation but as part of a pathway of care, agreed with partners across the whole system, which describes how all families can get the right help at the right time.

Referrals or recommendations typically come through a maternity, health or early years’ service provider from either statutory or voluntary sectors i.e. midwife, health visitor, children’s centre, GP, social worker, substance misuse or domestic abuse service, perinatal mental health.

In the early days of setting up a team, it can be helpful to prioritise communication with these more likely referrers. In all cases, the clinical focus for a specialised team is the parent-baby relationship and so all requests for service need to describe clearly how this may be in danger of being compromised currently or in the future.

Building relationships is important here: staff might request training from the specialised team to build confidence in identifying families to recommend, but equally parent-infant teams should take the time to understand the context and needs of the referring agencies.

It is worth spending time with your referrers so that you can design a process which fits well with their systems, ways of working and paperwork. This supports strong partnership working and effective pathways.

In some parent-infant relationship teams, self-referral is encouraged and in such instances the health visitor and GP as a minimum should be informed (following the usual consent to share information procedures).

The language of “referral” comes from health and social care and some families can find it stigmatising. An alternative is to describe the process as the “registration” or “recommendation” process. Both imply more ownership of the process by the family and may connote the offer of parent-infant work in a more strengths-based way.

Referrals are usually preferred in writing (email, letter, a template referral form see the Network area of this website for examples) but the process should strike a balance between collecting the necessary information and being quick and easy for referrers. Low referral rates can sometimes be traced back to lengthy or complicated referral processes.

Mapping the system

The ideal scenario is for agencies to work together to create an integrated perinatal and infant mental health pathway which clearly responds to the needs of both the child and parent(s). Working together in this way can establish good relationships between services and a better understanding of how each service works.

As a minimum, local services and their referral pathways should be clarified in relation to the new parent-infant team. For example, if there is a local Family Nurse Partnership, specialist infant mental health visitor(s), domestic abuse antenatal pathway, perinatal adult mental health team or pre-birth children’s services team, it is important to understand how these services are different, how families are referred to the most appropriate service, or transferred between services if necessary, and what an appropriate package of care might look like.

A specialised parent-infant relationship team can offer highly complementary input to all these services. Good care co-ordination starts with clarity in eligibility criteria and referral processes. Reaching across sectors, from voluntary to public and private and vice versa, is usually fruitful.

Establishing relationships with referrers and local services

There are several reasons to visit, communicate with and build relationships with referrers and other local services, including:

- To raise awareness about the importance of parent-infant relationship work

- To promote the team and their direct therapy, training and consultancy offers

- To discuss the referral criteria and what is an appropriate referral

- To support the shift in mindset towards the relationships being the client, not the baby or parent

- To begin to understand potential step up, step down and step out options and to think about opportunities for joint-working

‘Step up’ refers to the transfer of families from a lower intensity intervention, such as a universal parenting group or infant massage, into parent-infant work. ‘Step down’ refers to transfer in the opposite direction. ‘Step out’ refers to the transfer of families out of parent-infant work where the intervention has proven to be unsuccessful, inappropriate or the family have decided not to attend any more sessions but still want help of another kind. It is important to establish pathways into community-based services for all families as a way of creating or strengthening their social connectedness.

Setting up smooth transitions and referral pathways helps families feel held, maintains momentum in the progress they are making and can prevent repeat referral to crisis services. Planning these pathways in advance helps staff be clear about mutual expectations and facilitates relationships across teams. Recording these transfers can be helpful in reporting outputs and outcomes, which may also be useful for colleagues in maternity, health visiting and perinatal adult mental health teams who have a remit to support parent-infant relationships.

You may need to visit your referring colleagues regularly to stay up to date with changes in their services, discuss any issues in the referral pathway, to raise awareness of your service, engage with new staff, encourage appropriate referrals and communicate service changes.

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams are part of an ecosystem which promotes and protects the parent-infant relationship

Ensuring accessibility measures are in place for parents facing additional barriers to access

The Equality Act (2010) requires you to ensure your service is accessible to everyone who needs it. The government page “Making your service accessible: An introduction” [3] is a useful place to start. Accessibility considerations should include culturally diverse groups, parents with learning difficulties, autistic spectrum disorders or sensory needs and LGBTQI+ families. Part of your search for clinical venues needs to consider how all families will access them. Beyond the requirements of the law, there are other ways to be helpful – for example, thinking about the need for interpreters, stairs for families with buggies, or being close to bus routes.

The Network area of this website has several examples of leaflets for families and professionals to help you create your own.

Location

Ideally, a specialised parent-infant relationship team has one base which accommodates therapeutic and administration activities. Some teams are co-located with other services and this tends to enhance inter-professional relationships.

The therapeutic work of a parent-infant relationship team can be delivered in a range of locations and typically include: the family home, within the team’s base (if it has appropriate clinical spaces), children’s centres or other venues in the community as appropriate and convenient for families with young children.

Home visits may often be best for the family, especially at the beginning of work. It is anticipated that as their work progresses, families will become more confident to access other facilities in their community e.g. children’s centre, support from voluntary agencies such as Home Start, additional educational opportunities.

Therapy locations should feel physically and psychologically safe (for family and therapist) and this includes rooms which will not be interrupted. Home visits should balance the needs of the client with the safety of the therapist and no team can see all families at home all of the time. Some families will not attend venues which have past negative associations for them, and this may include schools, social care venues, churches or hospitals.

Community venues need to be accessible for pushchairs and disability needs, have accessible toilets including baby change facilities, offer baby feeding facilities and be clean enough to allow floor play. Rooms for group therapy sessions need to be comfortable (seating, room temperature, space to move about, adequate lighting).

Appropriate health and safety checks will be determined by local procedures. Staff inductions need to include fire evacuation, security access to the building, safeguarding reporting and accident reporting. Where home working is expected then adequate lone working and home visiting policies should be in place.

This website has examples of these in the Network area.

Recruitment, training, supervision and licences

All recruitment and supervision issues, including planning for the needs of professionally registered staff, are in Chapter 7 Recruitment, Management and Supervision.

Some therapeutic tools and approaches, for example the Key to Interactive Parenting Scale, stipulate licensing, re-licensing or supervision criteria and these may need to be built into the project plan and budget.

New multi-disciplinary teams may find it helpful to complete a core set of training together, for example VIG or one of the OXPIP or Anna Freud Centre ITSIEY courses (see Chapter 4 Clinical Interventions and Evidence-informed Practice). This facilitates team development, contributing to a better understanding of one another’s work and a shared focus on the parent-infant relationship. The AIMH-UK core competencies [4] also provide a framework to structure conversations between team colleagues about key skills and plans for continued professional development.

Purchasing equipment

Before you buy any video recording, editing or other IT equipment, make sure you understand your organisation’s position on the recording, storage and deletion of video material. For example, if your employer will not allow you to transfer video footage of families onto your work laptop, then this may have a significant bearing on whether you buy a video camera or a tablet with its own editing function. (Note: this needs to be addressed in your record keeping and archiving policy as well).

Other equipment you may need includes:

- Floor rugs and bean bags to ensure parents and therapists can sit on the floor next to babies*

- Baby changing mats

- Age-appropriate toys, dolls*

- Software to support data management (see Chapter 8)

- The manuals and record forms for licensed assessment tools

- Materials connected to specific approaches such as Five to Thrive (see Chapter 4)

* Consider health and safety requirements here such as whether items are fit for use with infants, cleaning / laundering etc

Writing policies and procedures including consent processes

Where teams are made up of staff from different agencies they may be expected to work to different agencies’ policies and procedures, in which case it can be helpful to identify a partnership board to iron out any inconsistencies.

Many parent-infant teams are located in sectors and organisations that already have a full suite of policies, such as home working, lone working, whistleblowing, consent to service, consent to share information, consent to record outcome measures, safeguarding and vulnerable adult policies. If not, local colleagues will likely have similar ones that can be adapted. The ParentInfant Foundation can support teams with this so if you cannot find an example of what you are looking for in our website’s Network area, please contact us directly.

Creating a communication, marketing and influencing plan

This is often an overlooked aspect of setting up a new team but can prove important in terms of later influencing and sustainability. Creating a communication, marketing and influencing plan means asking “who do you want to know what about the specialised parent-infant relationship team?”. Families can be involved from the start in helping to develop the service, the team name, etc. but also as a future audience for communications from the team.

Other typical audiences include commissioners and senior leaders (who might welcome quarterly, light touch updates with key outputs and outcomes), the early years workforce (who might welcome clinical updates, service updates and information about training opportunities), referrers (who will want feedback about referrals they’ve made but also might need reminding every now and again that the team is still there) and national audiences with whom you wish to network (e.g. the Parent-Infant Network).

Your plan might include a launch event, media and press outputs, leaflets and newsletters. The Parent-Infant Foundation may be able to share examples with you from other teams.

Creating a repository of case study material can be extremely useful for a range of purposes, so now is the time to think through your consent and retention policy.

A note about Implementation Science

There is increasing interest from practitioners, researchers and policy makers about the potential of “implementation science” to help improve how we deliver (or implement) services in ways which improve family engagement, retention and outcomes.

Implementation science is described by the Global Alliance for Chronic Disease [5] as “the study of methods and strategies to promote the uptake of interventions that have proven effective into routine practice, with the aim of improving population health. Implementation science therefore examines what works, for whom and under what circumstances, and how interventions can be adapted and scaled up in ways that are accessible and equitable.”

The House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Report [6] into Evidence-Based Early Years Intervention includes reference to the importance of implementation factors (pp 63-65) such as the importance of collecting data, accrediting training and supervision and model fidelity. Good review texts are available by Fixsen [7], [8] and Blase. [9] Implementation science also takes into its scope the capacities, motivations and opportunities for people to adopt new ways of working. For this aspect, we like the book Switch [10] by Chip and Dan Heath which provides an introduction to some key change concepts for non-specialists.

Making links with the Parent-Infant Foundation

If you are setting up a new team and have not yet contacted us, please do so. We are delighted to be able to share the information and resources we have, broker relationships with similar teams, learn about and promote your work, and hear about your challenges and successes. All specialised parent-infant relationship teams in the UK are invited to join the Parent-Infant Network, a collective space for peer support and learning.

We also have a newsletter specifically for parent-infant teams and a variety of other opportunities for teams to make use of. There is more information in Chapter 1.

Downloads

Footnotes

[1] HM Government The Charity Commission (Feb 2014). Public Benefit: rules for charities https://www.gov.uk/guidance/public-benefit-rules-for-charities

[2] Zero to Three. The Psychosocial and Environmental Stressor Checklist, DC:05 Resources, https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/preview/425bc4ce-5d05-49b5-9893-b279bf155243

[3] HM Government Accessibility Community (July 2019) https://www.gov.uk/service-manual/helping-people-to-use-your-service/making-your-service-accessible-an-introduction

[4] Association for Infant Mental Health UK (2019). Infant Mental Health Competencies Framework https://aimh.org.uk/infant-mental-health-competencies-framework/

[5] Global Alliance for Chronic Disease. Implementation Science https://www.gacd.org/research/implementation-science

[6] House of Commons Science and Technology Committee (November 2018). Evidence-based early years intervention https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmsctech/506/506.pdf

[7] Fixsen et al (2007) Implementation: The Missing Link Between Research and Practice https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED507422.pdf

[8] Fixsen et al (2005) Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/NIRN-MonographFull-01-2005.pdf

[9] Blase et al (2012) Bridging the Gap from Good Ideas to Great Services: The Role of Implementation http://www.cevi.org.uk/docs/Colebrooke%20Centre%20&%20CIB%20workshop%20March%207th%202012%20%20Karen%20 Blase%20Keynote%201%20slides.pdf

[10] Heath, C & Heath D (2011). Switch. Random House Business.

This chapter is subject to the legal disclaimers as outlined here.

This chapter is correct at the time of publication, 1st October 2019, and is due for review on 1st January 2021.