Chapter contents

Chapter summary

This chapter has three sections.

The first provides information about the professionals who make up a specialised parent-infant relationship team, their qualifications and registration. This will help you recruit appropriately qualified and experienced people.

The second section deals with the roles in specialised parent-infant relationship teams, so that you can plan the team structure.

The third section includes information about recruitment and there are helpful insights from existing teams about getting the management and supervision arrangements right. You will find sample job descriptions/role definitions and person specifications in the Network area of the Parent-Infant Foundation website.

You can download this chapter as a PDF here, or simply scroll down to read on screen.

Introduction

A parent-infant relationship team is a multidisciplinary team of professionals who fulfil a range of roles such as ‘clinical lead’ and ‘parent-infant therapist’. Roles can be filled by people from varied professional backgrounds but everyone in the team is bound together by a working knowledge of early child development, attachment theory, neurological development and an awareness of the importance of the unconscious dynamics of parenting.

The team offers a range of evidence-informed interventions so that every family can receive a tailored package of care. The team’s collective therapeutic toolbox should include individual and group interventions which can cater for a range of presenting difficulties and levels of complexity. Several existing teams employ a keyworker or similar family support colleagues who link families into other services such as housing, substance misuse or social isolation. This reduces families’ stress, facilitating their engagement in therapy and maximising its effectiveness.

Professions

Specialised parent-infant relationships teams tend to be made up of three complementary groups of practitioners:

1. Mental health professionals

These are practitioners who have a mental health-specific qualification, such as a psychotherapist, clinical psychologist, mental health nurse, counsellor or psychiatrist. Every parent-infant psychotherapist, and most clinical psychologists and child psychotherapists, are specifically trained in the theory and practice of early years work and so every parent-infant team should have at least one of these, ideally one psychotherapist and one clinical psychologist.

The Parent-Infant Foundation defines a specialised parent-infant teams as multidisciplinary which includes at least one clinical psychologist or child/parent-infant psychotherapist with excellent parent-infant knowledge, skills and experience.

Mental health professions are trained in a range of treatments and therapies although the depth and breadth of their training, and hence gradings, differ. Within each profession, individuals specialise in a particular age group and we recommend recruiters seek out relevant parent-infant specialism.

Psychotherapy is also the profession most closely aligned, philosophically and therapeutically, with attachment theory and the unconscious communication of parent-infant relationships. In the teams PIP UK supported to develop, parent-infant psychotherapy is an essential, but not exclusive, clinical component which provides psychodynamic thinking to the team. Other child mental health practitioners may have good early years’ experience and a deep understanding of psychotherapeutic approaches, but this will need to be checked at recruitment.

Mental health professionals might work as a Clinical Lead or Parent-Infant Therapist in specialised parent-infant teams. Alternatively, some teams recruit people into profession specific job roles, such as “Clinical Psychologist” or “Specialist Health Visitor”. This might be to enhance job appeal or to align with the employing organisation’s existing job profiles.

2. Health, education, social care or other related professionals

These are practitioners who have come into parent-infant work from a more generic background (e.g. health visiting, social work, early years, occupational therapy or family support work) and have specialist parent-infant skills by virtue of additional training, qualifications and experience.

3. Therapy-specific professionals

These are practitioners who are trained in one specific therapy, such as play therapists, cognitive-behaviour therapists or EMDR practitioners. They are from a wide variety of backgrounds, all having pursued a course of study and qualification in one chosen approach.

They may or may not have core therapeutic training but, as stated above, everyone taking up a role in a specialised parent-infant relationship team must have a working knowledge of early child development, attachment theory, neurological development and an awareness of the importance of the unconscious dynamics of parenting. In some teams, therapy-specific professionals are employed in the ‘parent-infant therapist’ role, in others they have a job title specific to their training, such as play therapist.

There are NHS National Job Profiles available on the nhsemployers.org website for:

- Psychologists, psychotherapists and counsellors [1]

- Occupational Therapists [2]

- Play Therapists [3]

- Art Therapy Staff [4]

- Health Visitors [5]

- NHS salary ranges (current as of 1 August 2019) can be found at healthcareers.nhs.uk [6]

Competencies, skills and qualities

The Association of Infant Mental Health in the UK (AIMH UK) has recently published a set of competencies for infant mental health work which brings welcome clarity to the competencies, skills and qualities needed to work at different intensities in parent-infant relationship work. We strongly recommend the AIMH Competency Framework which can be found at https://aimh.org.uk/infant-mentalhealth-competencies-framework/.

All parent-infant relationship practitioners should be at level three of the AIMH Competencies. Some teams require their practitioners to complete an infant observation course for the depth of understanding it develops regarding the world of infants.

All members of a team need to be nonjudgemental, compassionate, solutions-focussed and trauma-informed in their approach, and values-based interviewing can assist in identifying these qualities at recruitment.

Qualifications, Registration and Regulation

Neither “Parent-infant therapist” nor “Parent-infant psychotherapist” are protected titles. The former is a generic job title, the latter a speciality within the profession of psychotherapy.

A parent-infant therapist (or parent-infant practitioner) could be a person from any non-psychotherapy background (so a psychologist, social worker, health visitor, occupational therapist etc) who is employed in a role entitled Parent-infant therapist. For example, a Parent-infant therapist might be a specialist health visitor who has completed the ITSIEY modules at the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families, or could be a psychologist who completed a specialist placement in a parent-infant team. Parent-infant therapists are registered with the professional body responsible for their core professional qualification.

Psychotherapy is a distinct mental health profession with its own clinical training, qualifications and registration requirements. There are multiple different training routes to becoming a parent-infant psychotherapist. Some are child and adolescent psychotherapists whose training has covered the theory and practice of working with infants. Some are psychotherapists who have completed qualifications specific to parent-infant work, such as a Diploma in Parent-Infant Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. Psychotherapists are registered and regulated by whomever regulates the training course they completed to qualify as a psychotherapist.

Details of relevant Professional Bodies are listed at the end of this chapter and in the Bibliography.

Roles and team structure

There are various team structures and models around the UK but all comprise a range of roles with varying levels of skill and expertise. We describe below the roles of clinical lead, operational manager, parent-infant therapist, keyworker and administrator, and you will find example Job Descriptions and person specifications in the Network area of this website. Some teams additionally employ adult therapists.

As a minimum, a sustainable team requires a clinical lead, operations manager, two therapists and an administrator. The time commitment of each will depend on local population and birth rate per annum (see Chapter 3 Funding and Commissioning for more information).

i. Clinical Lead

The Clinical Lead acts as the guardian of clinical standards, providing clinical leadership across the team and supervising and supporting other staff. It is expected that this key member of the team has at least four years’ post-qualification experience and is working at NHS AFC Grade 8b and above. They will be trained as a clinical psychologist or a child/parent-infant psychotherapist and be registered with one of the relevant professional bodies (see Person Specification in the Resources Section). The Clinical Lead needs to be appreciative of the variety of approaches available for parent-infant relationships and highly skilled in at least one. They will be trained to supervise others and ideally have experience of leading a team and managing a service.

The role might include:

- Clinical management, recruitment, development and support of the clinical team, providing regular clinical supervision and supporting the therapists in their continued professional development

- Ensuring that the parent-infant team meets the needs of the local community and is embedded in established referral pathways

- Overseeing and managing systems for clinical audit which includes ensuring the completion and recording of outcome measures

- Working with the service manager to promote the team locally in order to secure ongoing funding

- Holding an appropriate caseload, this will depend on hours worked

- Leading the wider local workforce training on infant mental health, and the consultation offer

ii. Operational Lead/Manager

Depending on the structure and siting of the service within local structures, a local operations manager will work with the clinical lead to ensure an efficient and cost-effective service that is embedded within local systems. This team member may have a wider service remit i.e. CAMHS. This person is not normally a clinician and typically does not do clinical work.

The role might include:

- The business management, development and support of the service including identifying local need, working with the clinical lead on the development of the clinical team, referral pathways, linking up with local services and exploring innovative ways of working which reflect local needs

- Working with the clinical lead to understand the service data and how effectiveness can be improved, especially in relation to any impact reporting required by funders

- A responsibility to identify and apply for funding opportunities, or local commissioning, to ensure sustainability

- Developing and promoting the profile of their team locally with key early years services and organisations also working in the field of infant mental health

- Provide a link between the local parent-infant relationships team and PIP UK.

- Representing the team at a strategic level jointly with the clinical lead

iii. Parent-Infant Therapist

Parent-infant therapist is a generic title for any practitioner in the team whose work focusses on the parent-infant relationship. They typically work at the equivalent of NHS AFC high Grade 7 or low Grade 8 and will hold a recognised professional qualification, such as psychologist, social worker, health visitor, early years worker. They will be trained in the delivery of at least one parent-infant intervention i.e. parent-infant psychotherapy; Watch, Wait and Wonder; Circle of Security; Video Interaction Guidance (or similar); Mellow Parenting; Attachment and Biobehavioural Catch-up (ABC), etc. and ideally will also be trained in parent-infant observation.

The role might include:

- Providing a range of treatments for the referred families, focussing on the infant-caregiver relationship

- Applying all assessment and outcome measures as appropriate and ensuring that these are recorded on the data system

- Working and liaising with the local network of early years and adult mental health / perinatal services

- Offering consultation to other early years practitioners in the locality

- Presenting on topics related to infant mental health at local conferences and events

iv. Keyworker (grades vary locally)

Key/family workers within a team are key connectors and engagers of families to the service, and with other local services that might be identified as being able to offer the family additional assistance. These team members are trained in early child development and typically work within maternity or early years. Keyworkers may be seconded from or working in local services already embedded within the local community i.e. children centre workers, family support workers. They are usually supervised by a parent-infant therapist or more senior member of staff.

A major part of the Keyworker role is to support engagement through proactive outreach and casework for those parents who need extra help in order to access a parent-infant therapist. In addition, they may support families as the main worker where the help that a family needs from other agencies (e.g. housing, financial advice) needs to be put in place before the family is able to engage with other therapeutic modalities. The Keyworker will contribute to the outcome measures and may be in the best position to set up and run therapeutic groups. Many Keyworkers will be able to use pre-existing specialist skills, such as VIG or Mellow Parenting.

v. Adult Therapists

Some teams include (or buy in/second) practitioners who can deliver adult-specific interventions such as EMDR or CBT (see Chapter 4 Clinical Interventions and Evidence-Informed Practice). Their grades and skills depend upon the needs of the team.

vi. Administration and Data Manager

Each team requires a competent administrator to support the whole team and manage the data. This person typically works at the equivalent of NHS AFC Grade 4 and is managed by the Operational Lead.

The role might include:

- Providing the day-to-day administrative support for the clinical team

- General secretarial duties

- Ensuring all outcomes data is uploaded in a timely manner

- Being a central point of contact for general enquiries and unscheduled communication from families (e.g. sudden cancellations)

Other roles employed by specialised parent-infant teams include ‘Specialist Health Visitor’ or ‘Social Worker’, filled by practitioners from the relevant professions with additional training or experience in parent-infant relationships work.

Recruitment and interviewing

We recommend a minimum of a competencies-based interview and a values-based interview (if you have someone trained in VBI available) to secure appropriately qualified staff with the ideal mix of qualities. Values-based interviewing is a specific model of interviewing which translates the values of an organisation into exploratory questions. It is widely used by the NSPCC and various NHS organisations and Local Authorities. The values-based interview can help recruiters assess a candidates’ suitability to work with the emotional states of infancy.

Because the training and qualification routes into parent-infant work are varied, recruiters should ask candidates about their parent-infant knowledge, skills, experience and any specific training, as well as which professional body they are regulated by.

Some areas are experiencing recruitment shortages in certain professions, leading to compromise in the job description or grading. Creating generic posts (e.g. Parent-infant therapist) may broaden the scope of who can apply but may be less appealing to those looking for the career benefits of a profession-specific post (e.g. Specialist health visitor).

Recruitment offers an opportunity to involve service users/beneficiaries, for example in the way the job description and person spec are written and/or in the interview panel.

Supervision

This section covers three types of supervision:

- Clinical and model-specific (talking about the direct work with families with a more experienced therapist)

- Professional (talking with a more senior member of the same profession about the role and its responsibilities)

- Safeguarding (talking with a safeguarding specialist about families)

These are all distinct from line management which is the operational leadership of an individual to include performance management, welfare and practicalities such as details of deployment, contracts, annual leave, etc. It is not uncommon for your line manager also to be your clinical or professional supervisor, although there are benefits in separating out these roles, namely decoupling reflective learning and restorative functions from performance management functions and being able to access different kinds of expertise.

Professional body requirements differ and we recommend that recruiters familiarise themselves with the guidance from the relevant organisation.

Contact details of the main professional bodies are listed at the end of this chapter.

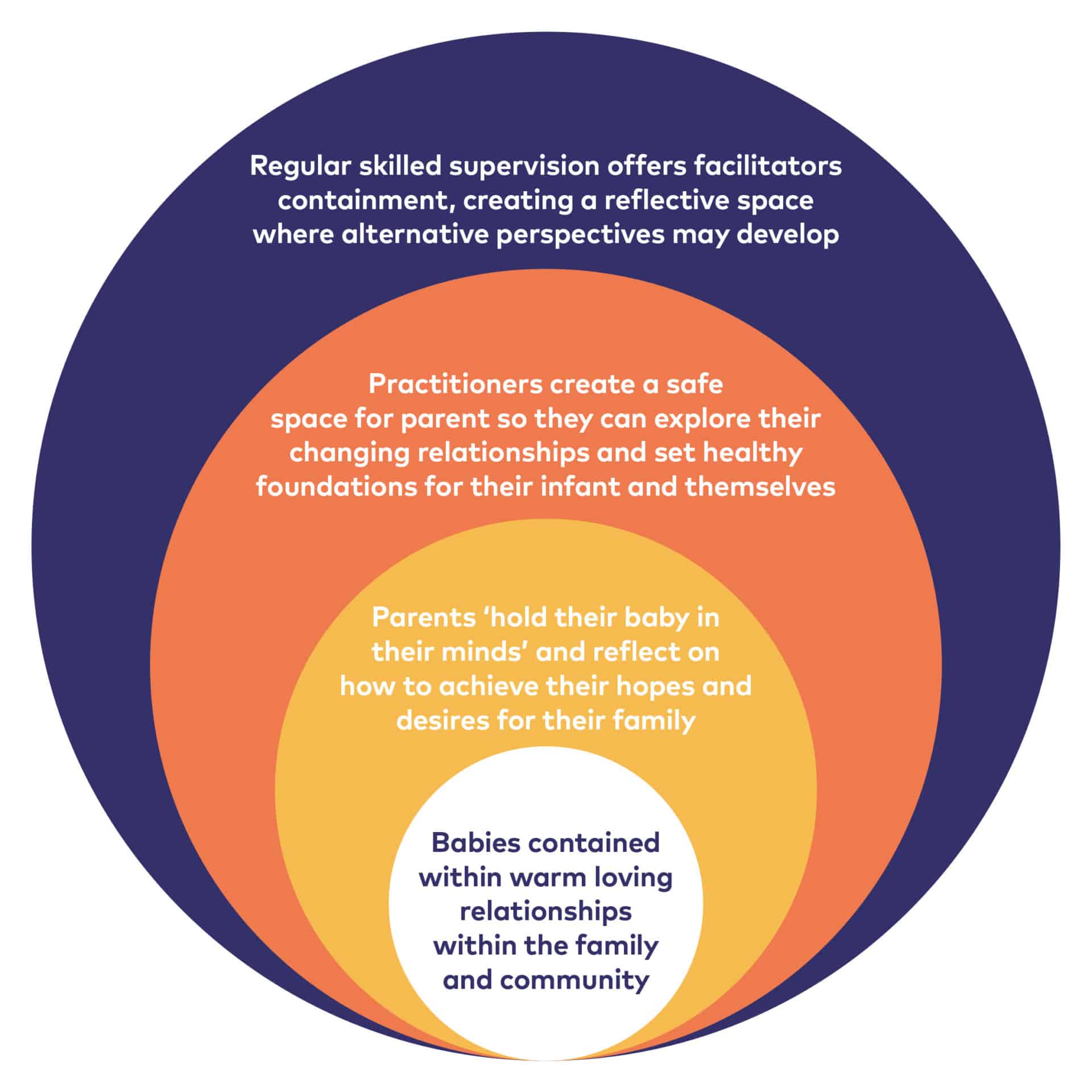

Supervision supports the reflective functioning between therapist and family and between parent and infant

Clinical and model-specific supervision

All team members (not just those from certain professions) should receive regular clinical supervision from an appropriately-qualified supervisor. This may be the clinical lead, a senior therapist in the team or an appropriate external supervisor. The supervision should be a reflective, restorative and formative experience for the supervisee. The ParentInfant Foundation suggests that the minimum should be one hour every two weeks, more for less-experienced practitioners or those with particularly complex caseloads.

The minimum clinical supervision time set by the Association of Child Psychotherapists is two hours a month for a newly-qualified child psychotherapist and, after two or more years’ full time experience, this may be one hour a month from a consultant child psychotherapist.

Some interventions, such as VIG, require practitioners to access regular model-specific supervision from an appropriately qualified supervisor, on top of their regular clinical supervision.

The clinical supervision arrangements for clinical leads can be harder to address as there may be no one in their locality more experienced than them. Most clinical leads find a bespoke solution: peer supervision with other clinical leads, supervision from senior clinicians in other specialties, or buying in supervision from private consultants.

Professional supervision

Where clinical supervision is provided by someone from a different profession, it is usually a professional requirement for staff also to receive profession-specific supervision every now and again, although professional bodies differ in their guidance about this. Profession-specific supervision reflects on how the person is executing their role and responsibilities according to the expectations of their profession, and is being supported by the organisation to do so.

Safeguarding supervision

This supervision provides a reflective space to concentrate on how best to keep all children safe. It is not a professional requirement for mental health professions but may be an organisational or departmental requirement. Safeguarding is emotionally draining work and good safeguarding supervision should be restorative as well as formative. Specialised parent-infant relationships teams located in the NHS or local authorities will have good access to safeguarding specialists, but it may be harder for charities or CICs. The NSPCC has safeguarding information for voluntary and community organisations on its website https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/safeguarding-child-protection/for-voluntary-and-community-groups/ including information about safer recruitment.

A note about personal therapy

Working with infants and their parents is very likely to stir up strong emotions in therapists as it is intense work. Parents and babies require different responses from the therapist, who has to hold both positions in mind without identifying with one more than the other. The parent-infant relationship resonates with every individual, both from childhood and in parenthood, so this work can trigger suppressed feelings. Without reflection on these issues, therapists may risk re-enacting their own unresolved traumas which could be psychologically harmful to the families they work with.

Good quality supervision helps therapists become more conscious of their own responses to the work but may not necessarily help change them. Personal therapy provides insights into what they might be feeling and why, leading to a greater awareness of where their blind-spots are. Everyone has patterns of interaction that can be unhelpful to the work with families, so many therapists access personal therapy either regularly or intermittently to support their professional practice.

In today’s financial climate, it is hard to imagine employers being in a position to fund this type of support for therapists, although occasionally personal short-term psychotherapy is available through Employee Assistance Programmes. However, employers may be able to support therapists with finding a suitable therapist and allowing time to attend personal therapy sessions.

Management and leadership

The Parent-Infant Foundation promotes the ethos that any programme aiming to improve the relationship between parent and baby can only succeed if it is embedded within a ‘relationship-based organisation’ [7] , This is sometimes referred to as the parallel process, where the quality of relationships within the team match the quality of the relationships they aim to form with and so foster within families. This takes skilled and committed leadership. Non-clinical managers may find restorative leadership training helpful.

The Parent-Infant Network, which the Parent-Infant Foundation facilitates, can be an invaluable place to access other team managers to discuss common challenges and shared solutions. Bringing together a new multi-disciplinary, sometimes multi-agency or multi-sector team, can raise interesting questions about professional identities, cultures, roles and language. Other managers are an invaluable source of support and information and the Parent-Infant Foundation is happy to broker peer support relationships where we can.

Training and Continuous Professional Development (CPD)

As a minimum, all practitioners are expected to remain up-to-date in evidence and practice and to fulfil the Continuous Professional Development (CPD) needs to remain registered with their professional body. This is likely to affect social workers, health visitors and midwives the most, as they may need to return to traditional practice after a period of time in another post or maintain their practice via a split post.

However, teams should aspire to do more than the minimum in terms of regular training. In particular, teams tell us there is significant value in the whole team training together in core theory, assessment and interventions. The selection of these trainings will differ in each team, although Chapter 4 Clinical Interventions and Evidence-Informed Practice introduces some of the options. Teams who have share some core training have an increased mutual understanding and shared language of the theoretical principles underpinning their collective work and this enables improved communication.

The accreditation and supervision requirements for some interventions need to be addressed and built into budgets. In some cases, practitioners can train to be supervisors/ trainers for those interventions which require it, this builds internal capacity and reduces costs for colleagues.

Professional bodies

All health, psychological and social work professionals should be registered with the Health and Care Professional Councils (HCPC) who regulate these professions via their Code of Conduct https://www.hcpc-uk.org/. As of 2 December 2019, the HCPC will transfer their social worker regulation responsibilities over to Social Work England (https://socialworkengland.org.uk/).

Psychologists may also optionally be members of the British Psychological Society (www.bps.org.uk).

The British Association of Social Workers (https://www.basw.co.uk/) acts as both a professional membership body and union for social workers.

Health visitors must maintain their registration as a nurse or midwife with the Nursing and Midwifery Council (https://www.nmc.org.uk/). The Institute of Health Visiting (www.ihv.org.uk) is a professional membership body for those working in Health Visiting.

The Royal College of Midwives is a professional membership body and trade union specifically for midwives (www.rcm.org.uk)

Psychotherapists are registered and regulated by whomever regulates the training course they completed. For example, the Association of Child Psychotherapists (https://childpsychotherapy.org.uk/) registers child and adolescent psychoanalytic psychotherapists who have qualified via one of the following training schools and completed the NHS funded four-year clinical training:

- Birmingham Trust for Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, Birmingham

- British Psychotherapy Foundation, London

- Human Development Scotland, Glasgow

- Northern School of Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy, Leeds

- Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, London

These training schools provide ACP child psychotherapists with competencies aligned to or exceeding Level 3 of the AIMH-UK competencies.

The UK Council for Psychotherapy (www.psychotherapy.org.uk/) accredits the Diploma in Parent-Infant Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy run by the School of Infant Mental Health in London.

Downloads

Footnotes

[1] NHS. National profiles for clinical psychologists, counsellors & psychotherapists. https://www.nhsemployers.org/-/media/Employers/Documents/Pay-and-reward/Clinical_Psychologists-Counsellors.pdf?la=en&hash=02CA64816455E0A3B5B8DE22CFB30489F2A654DF

[2] NHS. National profile for occupational therapy. https://www.nhsemployers.org/-/media/Employers/Documents/Pay-and-reward/Occupational_Therapy.pdf?la=en&hash=DB121FCC1F78FAACFBB61F7A2823EF944E5433E7

[3] NHS. National profiles for play specialists. https://www.nhsemployers.org/-/media/Employers/Documents/Pay-and-reward/Play_Specialists.pdf?la=en&hash=B731A847EF87CF06F3A40E7D810C0AEB24FCC6FC

[4] NHS. National profiles for art therapists. https://www.nhsemployers.org/-/media/Employers/Documents/Pay-and-reward/Art_Therapy.pdf?la=en&hash=FA276BE3C252B42A0EB3F80EDB674BF1AD652899

[5] NHS. National profiles for health visiting. https://www.nhsemployers.org/-/media/Employers/Documents/Pay-and-reward/Health-Visitors-current-version-291118.pdf?la=en&hash=44073CFF26552097BA35E68929891F59390D4E73

[6] NHS Health Education England. Agenda for Change pay rates (April 2019). https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/working-health/working-nhs/nhs-pay-and-benefits/agenda-change-pay-rates

[7] Bertacchi, J. (1996) Relationship-based organizations. Washington, DC: Zero to Three, 17, (2), 1-7

This chapter is subject to the legal disclaimers as outlined here.

This chapter is correct at the time of publication, 1st October 2019, and is due for review on 1st January 2021.