Chapter contents

Chapter summary

This chapter will help you understand and communicate the reasons why every area in the UK needs a specialised parent-infant relationship team.

- We condense the compelling case for parent-infant teams, and their associated systems-level work, into ten easily-communicated key messages

- We summarise the scientific, moral and economic arguments with reference to research and policy

You can download this chapter as a PDF here, or simply scroll down to read on screen.

Introduction

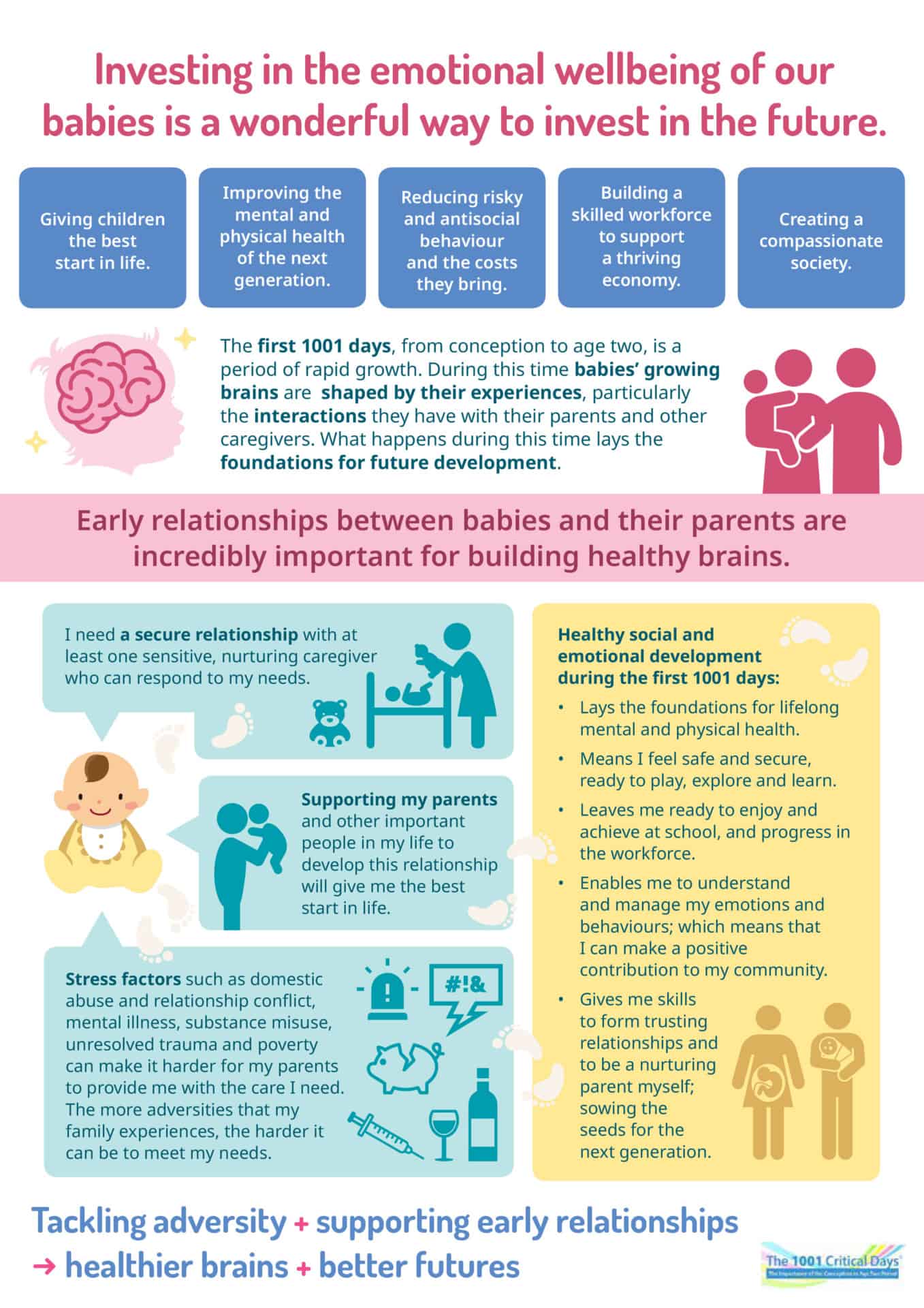

The first 1001 days of life, from conception to age two, is a time of unique opportunity and vulnerability. It is a period of particularly rapid growth, when the foundations for later development are laid. During this time, early interactions and relationships between babies and their parents are incredibly important for healthy brain development. Persistent and severe difficulties in early relationships can have pervasive effects on many aspects of child development, with long term costs to individuals, families, communities and society. This is recognised in numerous national and international policy documents and reports, with increasing calls for investment.

We have a unique window of opportunity to intervene, at the start of a babies’ life from conception onwards, when parents are often receptive to help and in contact with universal services. Yet, specialised interventions which focus on the parent-infant relationship are commonly not available in universal services, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) or perinatal mental health teams.

Therapeutic work with babies is different from work with older children and requires a specific set of competencies. It is skilled work that requires specialist expertise in child development and the unconscious communications between parents and their babies and between both of them and the therapist.

The opportunities and risks during the first 1001 days and the need for practitioners to have specific expertise to work effectively with families during this period, create a strong case for the existence of specialised parent-infant relationship teams.

This chapter explains ten different elements of this case for action in more detail.

- The first 1001 days are a crucial time and what happens in this period influences lifelong health and wellbeing

- Relationships, especially the parent-infant relationship, are at the heart of healthy development

- Early adversity brings costs to individuals, society and the public purse: investments in early life pay the greatest dividends

- There is increasing international and national recognition of this important work

- We have a unique opportunity to intervene when parents are generally receptive to help and in touch with services

- Specialised parent-infant relationship interventions are commonly not available in existing provision

- Early social and emotional development lays the foundation for a range of important life outcomes which feature in policy priorities

- A significant number of babies are at risk in the UK

- Babies are currently largely ignored in policy, commissioning and practice

- Specialised parent-infant relationship teams can drive systems change

The first 1001 days are a crucial time and what happens in this period influences lifelong health and wellbeing

It is now widely recognised that what happens in the first 1001 days of a child’s life is key to enabling that child to survive and thrive[1]. Children’s brains develop fastest and are at their most ‘plastic’ or adaptable in the womb and early years of life. This is when the foundations are laid for later development. Many millions of neural connections are made and then pruned as the infant adapts to his or her unique family setting, and the initial architecture of the brain is developed[2].

Children’s development is shaped by their environment, especially the relational environment. By supporting early development we have the opportunity to put children on a positive developmental trajectory, better able to take advantage of other opportunities that lie ahead. Conversely, if babies have a difficult start it can have pervasive effects on multiple domains of child development[3].

“The period from pregnancy to age three is when children are most susceptible to environmental influences. Investing in this period is one of the most efficient and effective ways to help eliminate extreme poverty and inequality, boost shared prosperity, and create the human capital needed for economies to diversify and grow”

Unicef, World Bank and World Health Organisation Nurturing Care Framework

Relationships, especially the parent-infant relationship, are at the heart of healthy development

Babies’ development is strongly influenced by their experiences of the world and these are shaped by their primary caregivers (usually their parents). Parent-infant relationships are vitally important, especially for building the brain architecture upon which other forms of development will rest. Yet, specialised interventions are commonly not available in local areas. In parent-infant teams, the “client” is the relationship that is developing between the baby and his or her parents.

“Young children experience their world as an environment of relationships, and these relationships affect virtually all aspects of their development." [4]

Nurturing relationships begin before birth. How parents feel about their unborn baby influences their antenatal care. The foetal brain is developing rapidly during pregnancy, changing in response to the biochemical experience of the mother’s mental[5] [6] [7] and physical health[8] [9] and to substances she may ingest, such as alcohol[10]. This process, known as foetal programming[11], ensures the baby is highly adapted to the world into which it will be born.

Babies’ brains are sensitive to both the physical health environment of the mothers’ womb and the relational environment beyond it. Babies recognise their mother’s and father’s voice in the womb[12] probably as part of an innate drive to seek out those voices after birth. Babies can even experience adversity in the womb. For example, where domestic abuse is occurring, babies’ stress regulation systems can adapt accordingly, leaving them more responsive to threat but consequently more irritable and difficult to settle once they are born[13].

Babies are reliant on parents to respond to their needs. Parents who are tuned-in and able to respond to babies’ needs sensitively in an appropriate and timely way, support their early development in profound ways:

- Parents’ responses shape how babies experience their emotions and how they learn to regulate and express these emotions. If someone responds sensitively to a baby when they cry, the baby learns that they matter, that they can rely on their parents to help them when they are upset, and how difficult emotions can be brought under control[14].

- When babies receive appropriate comfort and care, they can feel safe and begin to explore the world around them, to play and learn[15].

- When parents provide positive, playful interactions, and when they engage in play and activities such as singing and reading to their baby, this provides stimulation that helps a child to learn and develop[16] [17].

Babies and toddlers have no choice but to adapt to their family’s emotional habitat. When the infant finds consistent stress rather than comfort within the family then survival takes precedence over emotional connection.

If a child’s emotional environment causes them to feel unsafe or fearful, or if they experience toxic stress in the absence of relationship which can help them regulate or buffer their stress[18], this will be reflected in their psychological and neurological development and will influence how their brain develops to deal with stress in later life.

A 2019 study by the Child Trauma Academy in Houston[19] found that a severe lack of positive relational experiences in the first two months of life changes the child’s self-regulation and sensory integration systems and may be particularly influential for neurodevelopmental or brain-related outcomes. The study also found that early-life stress in one developmental period was likely, in the absence of intervention, to carry on into the next developmental period.

The large Adverse Childhood Experiences[20] studies have demonstrated a clear association between childhood trauma and a range of poorer outcomes across the life course, including obesity, substance misuse including alcoholism, smoking, mental health problems such as depression, physical health problems including cancer[21] and age-related diseases such as dementia and diabetes[22].

Attachment theory is a framework that is commonly used to describe and understand patterns of emotionally-significant relationships in both children and adults. Its importance lies in its explanation that early parent-child relationships lay the blueprint for future relationships. This “template” for relationships is always open to change but reflects the child’s adaptation to the emotional availability of the parent(s).

The longer this interaction goes unchallenged, the greater the influence over how the child will anticipate the behaviour of others, conduct relationships and manage ruptured relationships. What happens between an infant and her caregiver is therefore vitally important. It is important not only for the way the infant will come to relate to herself and to other people, but also for her developing capacity to think[23].

There are four commonly-used ways to describe children’s patterns of attachment: secure, avoidant, ambivalent (or resistant) and disorganised. Children who have received sensitive, responsive care generally display secure attachment (estimated prevalence 60-65% of the general population[24] [25]).

Secure attachment is a broadly protective factor, conferring confidence, resilience and adaptability, although it does not provide a total guarantee of future mental health. Disorganised attachment is the category posing the most serious risks to future development[26]. This form of attachment is frequently, although not always, associated with maltreatment within the family.

Disorganised attachment is always a reason to offer specialised help and for very young children that specialised help is commonly not available in existing provision. At least 15% of children in the general population experience a disorganised attachment and this figure is higher for children facing adversity[27].

We recommend the NICE final scope document[28] as a concise source of further information about attachment styles including disorganised attachment and Levy and Orlans (2014)[29] for a more comprehensive introductory text.

Early adversity brings costs to individuals, society and the public purse: investments in early life pay the greatest dividends

“It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men”[28]

Children experiencing extremely difficult family relationships are more likely to struggle in a number of domains of development[31]. From therapeutic experience, these are children who often feel frustrated and unhappy for reasons they cannot put into words. Without specialised help, such as is offered by a specialised parent-infant relationship team, a child might go through life responding to even minor problems as if they were a dangerous life-threatening situation[32]. This hyper-reactivity can underpin later problems in self-control[33] which affect behaviour, education, employment and adult relationships. This brings costs not only to the individual, but also to the community, public services and the wider economy.

Toxic stress is the prolonged activation of the stress response systems in the absence of protective relationships. Early traumatic experiences and toxic stress are associated with an increased risk of a wide range of poor physical and mental health outcomes[34], including major public health issues such as depression, cancer and dementia, with costs to individuals, families, communities and the public purse[35]. The impacts of early adversity can be overcome, but it is harder and often more costly to improve children’s lives later rather than getting things right from the start[36].

Improving early relationships could prevent and/ or mitigate the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). If babies do not have sensitive and responsive early relationships, this relational trauma can have pervasive effects on multiple domains of child development. Secure relationships confer resilience, which buffer children against the negative impacts of adversity[37]. Conversely, a challenging home environment is itself an adversity and can increase the impact of other challenges that affect a child’s wellbeing and development[38].

Return on investment

A number of publications have estimated the costs of ‘late intervention’ in children’s lives. For example, mental health problems in children and young people are associated with excess costs estimated at between £11,030 and £59,130 annually per child. These costs fall to a variety of agencies (e.g. education, social services and mental health and include the direct costs to the family of the child’s illness)[39].

James Heckman has shown that money spent on interventions at this stage of the life course brings the greatest dividends[40]. This is because:

- It is relatively easier and more effective to act early (prevention is better than cure)

- The families with the greatest need for specialist early intervention tend to make the greatest gains from it

- Early action leads to accumulated savings by preventing other services being required later in the child’s life

- Effective early intervention improves the child and family’s participation in the economy

“What is one of the best ways a country can boost shared prosperity, promote inclusive economic growth, expand equitable opportunity, and end extreme poverty?

The answer is simple: Invest in early childhood development. Investing in early childhood development is good for everyone – governments, businesses, communities, parents and caregivers, and most of all, babies and young children.

It is also the right thing to do, helping every child realize the right to survive and thrive. And investing in ECD is cost effective: For every $1 spent on early childhood development interventions, the return on investment can be as high as $13.”

Unicef, World Bank and World Health Organisation Nurturing Care Framework

There is increasing international and national recognition of this important work

There is now global recognition of the need to prioritise early childhood development.

The World Health Organisation, UNICEF and the World Bank, in collaboration with the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health, the Early Childhood Development Action Network and many other partners, have developed the Nurturing Care Framework.

The framework outlines:

- Why efforts to improve health and wellbeing must begin in the earliest years, from pregnancy to age three

- The major threats to early childhood development

- How nurturing care protects young children from the worst effects of adversity and promotes physical, emotional and cognitive development

- What families and caregivers need to provide nurturing care for young children

“Investing in early childhood development is one of the best investments a country can make to boost economic growth, promote peaceful and sustainable societies, and eliminate extreme poverty and inequality. Equally important, investing in early childhood development is necessary to uphold the right of every child to survive and thrive.”

World Health Organisation[41]

England

The recent Prevention Green Paper recognises the importance of the first 1001 days:

“We start building our health asset as a baby in the womb. The first 1,000 days of life are a critical time for brain development, and parents and carers have a fundamental role to play in supporting their child’s early development...

We know that a wide range of longterm outcomes are improved through the positive relationships established between parents and carers and their baby from pregnancy onwards.”

Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s – consultation document[42]

In recent months, the Government has been criticised for not having a strategic approach to giving children the best start in life. There is a lack of leadership and accountability nationally and locally for work to support the first 1001 days, as recently recognised by three separate recent Select Committees.

“Recently the Government has tended to focus on intervening later in childhood. The Government’s approaches to children’s mental health, obesity and even early childcare care focus more on intervening after age two than earlier in the crucial first 1000 days.

Where Government and public services do intervene in the early years, we have found that it has done so in a fragmented way, without any overarching strategic framework and with little join-up.”

Health Select Committee 1000 Days Inquiry[43]

An inter-ministerial group, chaired by Andrea Leadsom MP, was established to look at how Government might improve the coordination of its work for families in the early years of life. However due to recent developments in Westminster, the future of this work is not clear.

The NHS Long Term Plan for England states that “Over the coming decade the goal is to ensure that 100% of children and young people who need specialist care can access it”[44]. Delivering this goal would require the NHS to ensure that 100% of children under two who need specialist care could access it which would mean providing specialised parent-infant relationship teams.

Funding to deliver on the NHS Long Term Plan will shortly enter Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) baselines. All CCGs (or equivalent structures) must create a strategic plan for how they will spend their money before Christmas 2019.

Wales

There is increasing recognition of the importance of infant mental health in Wales. The Welsh Government’s programme for Government 2016-2021, Prosperity for All[45] includes a cross-cutting priority for all children to have the best start in life, recognising the importance of the first 1000 days. Public Health Wales are leading work with a group of stakeholders to make infant mental health a central part of the First 1000 Days framework which will be published later this year.

Scotland

The Scottish Government has an aspiration to make Scotland the ‘best place to grow up’ and has a strong focus on reducing inequalities in outcomes. There is a strong and consistent focus on early years, prevention and early intervention in Scottish government policy.

Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC)[46] is the national approach to improving children’s wellbeing. GIRFEC aims to provide a common framework and language for all those working with children. The Early Years Framework[47] sets out the importance of early intervention, particularly in the early years and set out an ambition to give all young children in Scotland the best start in life.

This has been followed by a range of policy developments to support the first 1001 days, such as national roll-out of Family Nurse Partnership and the introduction of the Best Start grant for low-income families.

The Scottish Government’s Programme for Government, published in September 2019, announced £3m to support the creation of integrated infant mental health hubs,

described as a multi-agency model of infant mental health provision to meet the needs of families experiencing significant adversity, “including infant development difficulties, parental substance misuse, domestic abuse and trauma”[48] This delivers on commitments made in 2018, in the Mental Health: Programme for Government Delivery Plan and the recommendations of the national managed clinical network in February 2019[49]. Additional investment has also been announced to enhance infant mental health provision within Scotland’s two specialist inpatient Mother and Baby Units, and to improve community-based support delivered by the third sector.

There were no specialised parent-infant relationship teams reported in Scotland during the Freedom of Information for the Rare Jewels (2019) report, although some CAMHS services do offer some types of parent-infant work and the NSPCC has a specialised team in Glasgow which provides a service solely to young children in foster care.

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, work to promote infant mental health is being led by the Public Health Agency. In 2016, the Public Health Agency developed an Infant Mental Health Strategic Framework. The document was prompted by a desire to reduce health inequalities by giving children the best start in life, and was informed by conversations with a range of international experts. It represents “a commitment by the Public Health Agency, Health and Social Care Board and Trusts, as well as academic, research, voluntary and community organisations across Northern Ireland, to improve interventions from the antenatal period through to children aged three years old”[50].

The Framework aims to ensure that commissioners and policy makers are fully informed of the latest evidence and interventions and are supported to make the most appropriate decisions based on this knowledge.

It also aims to improve the skills of practitioners across a wide range of health, social care and education disciplines to support parents and children aged 0-3 in the development of positive infant mental health, and encourages service development “to ensure the optimum use of evidence based interventions with families with children aged 0-3 where there are significant developmental risks.”

Two new parent-infant relationships services have been developed in Northern Ireland, the ICAMHS service, which is hosted within CAMHS in the Southern Health Trust, and the ABCPiP team in South Eastern Health Trust.

We have a unique opportunity to intervene when parents are generally receptive to help and in touch with services

The first 1001 days of a baby’s life are an important period of transition for parents too and one that can bring challenges. This is a time of huge social, psychological, physical and relationship change. Most parents will have some contact with maternity services during this period which provides an opportunity for engagement and referrals or signposting to other services.

Parents are preparing to relate to their baby during pregnancy. There is evidence to suggest that parents’ perceptions of their foetus are associated with the quality of their relationships after birth, and that maternal-foetal attachment is associated with later child outcomes[51] [52].

Practically all parents want to do their best, to enjoy their relationship with their baby and to give their baby the best start in life. Therefore parents, even those who have had difficult relationships with professional services in the past are often most receptive to help during the final months of pregnancy and the first months in their baby’s life[53].

Parents who are going to struggle to establish a healthy relationship with their child are often identifiable during pregnancy and the early months of parenthood, sometimes because they are not receptive to care as usual. Indeed, serious case reviews of adolescents often highlight warning signs from this early time: parents who didn’t attend antenatal appointments, baby weighing clinics, or immunisations.

Specialised teams can offer timely, effective early interventions to see off the risks and get the parent-infant relationship back on track. This takes time, patience and skill to engage the most vulnerable or suspicious parents.

If we can capture and build on parents’ motivations during pregnancy and the early days and offer them a service which is engaging and feels helpful to them, we can make a huge difference to the whole family and set a template of positive engagement with services that can continue through the child’s life.

Specialised parent-infant relationship interventions are commonly not available in existing provision

At least 15% of babies in the general population need specialised parent-infant relationship interventions which are beyond the scope of universal services and are commonly not available elsewhere, including from CAMHS. In England, 42% percent of CCGs report that their CAMHS service does not accept referrals for children under two years, and even in areas where CAMHS might on paper take referrals for younger children, children aged two and under are rarely seen[55].

Some perinatal mental health services offer parent-infant work, and this is welcome, but this is only available where mothers have significant mental health problems that meet the thresholds for these services. So, despite the importance of early relationships, most babies live in an area where they cannot access the specialised help they need.

Therapeutic work with babies is different from work with older children and requires a specific set of competencies: practitioners need the ability to work with parents, babies and crucially their relationships. This is skilled work that requires specialist expertise in child development and the unconscious communications between parents and their babies and between both of them and the therapist.

Early social and emotional development lays the foundation for a range of important life outcomes which feature in policy priorities

Early relationships, and the social and emotional development that results from them, play an important role in how well a child will go on to achieve many of the key outcomes that public, professionals and policy makers care about.

Education

Babies who have had good early relationships start school best equipped to be able to make friends and learn[56] [57] [58]. This increases the chances that they will achieve their potential in later life and contribute to society and the economy.

A child’s early relationships shape their perceptions of themselves and others and teach them how to regulate their emotions and control their impulses. Children who can control their emotions and behaviours are better able to settle into the classroom and learn. They have a template for positive relationships, which builds self-confidence and self-esteem, and can strengthen their relationships with peers and teachers.

Research suggests that emotional development in childhood has a greater impact than academic skills such as literacy and numeracy on adult outcomes such as mental wellbeing, physical health (such as obesity, smoking and drinking), and a similar impact on outcomes such as income and employment[59].

Emotional and physical health and wellbeing

Emotional regulation, one aspect of emotional development shaped by early attachment relationships, is at the heart of many of the challenges currently concerning policy makers. Better self-regulation is strongly associated with mental wellbeing, good physical health and health behaviours and socio-economic and labour market outcomes[60]. Emotional regulation is at the heart of the specialised interventions offered by parent-infant teams.

Young people who can regulate their emotions and behaviours and develop positive relationships are more likely to have good mental health from the early weeks of life and to avoid risky, harmful or antisocial behaviour such as self-harm[61] and youth violence[62].

Poor emotional regulation in the early years is a proven risk factor for later adolescent violent crime[63]. Healthy and loving relationships enable children to develop the capacities they need to participate in society and to lead happy and fulfilling lives.

Language and literacy

Healthy parent-infant interactions help children’s early language development, which is facilitated when parents talk, sing and read books with their children[64].

Parenting capacity

A child’s experience of being parented also influences how they go on to parent their own children; supporting babies’ brain development pays dividends for generations to come[65].

Social mobility

Growing up in a low-income family is associated with poorer emotional health and development[66]. This is likely to be a contributing factor to worse outcomes that children and young people from lower income families experience across a wide range of domains. Any strategy to support social mobility must therefore include acting early to support emotional development, to close gaps between disadvantaged children and young people and their peers[67].

Healthy social and emotional development can also help to protect children against the impact of poverty and adversity. One study found that boys who lived in poverty but had secure attachment relationships were 2.5 times less likely to have social and behavioural problems later in childhood[68].

A significant number of babies are at risk in the UK

Urgent action is required to support parent-infant relationships now, given the number of babies who are vulnerable or experiencing harm and the lack of availability of specialised teams to support them.

There is no robust data on the number of babies experiencing poor relationships with their primary caregivers in the UK but a range of research suggests that a significant number are living in circumstances that might put their emotional wellbeing and development at risk.

Around 15% of children in the general population have a disorganised attachment with their primary caregiver, although prevalence depends on the social profile of the community and is much higher in vulnerable groups: children of mothers experiencing domestic violence at 57%[69] , of mothers using drugs and alcohol estimated at 43%, of mothers with depression estimated at 21%[70]. Disorganised attachment is beyond the scope of what typical universal or early help services can offer as it requires specialised interventions delivered by specialist practitioners

The latest comprehensive data available for England found that there were 19,640 babies under a year old identified by Local Authorities as being ‘in need’, largely due to risk factors in the family home[71].

Babies are at particular risk when they live in households where parental mental ill-health, domestic violence and/or substance misuse are present. NHS Digital’s 2014 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) suggests that 25,000 babies under one in England live in a household where two of these three risk factors are present and 8,300 live in a household where all three are present[72]

An epidemiological study in Denmark found mental health problems in 18% of 1½ year-old children from the general population[73]

We are seeing the costs of poor mental health and emotional wellbeing in older children:

- Nearly 18,000 children in England accessed children and young people’s mental health services last year, a number that is rising steadily

- 1,032,898 children in England self-reported emotional and mental health issues in 2017, a 50% increase from 2004[74]

Mental health problems are a risk factor for youth violence and school exclusion. Youth violence is rising, with increasing concerns about knife crime.

School exclusions are also rapidly increasing. The total number of permanent exclusions in England increased by 60% between 2013/14 and 2017/18, with on average 42 pupils expelled every school day[75]

In 42% of Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) areas in England CAMHS services do not accept referrals for children aged two and under.

Babies are currently largely ignored in policy, commissioning and practice

Despite the incredible importance of the first 1001 days, babies are often forgotten about and easily ignored in policy, commissioning and practice. Whilst 0-2 year olds should receive an equal, or even a greater share of attention, spending and service provision, they often miss out.

Research by the Parent-Infant Foundation found that despite CAMHS nominally being a service for 0-18 year olds, in 42% of Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) areas in England CAMHS services do not accept referrals for children aged two and under.

Even where services might accept referrals, many do not actually see many children in this age range[76].

There are a number of reasons for this, including:

- Very young children who are experiencing distress and poor emotional wellbeing may not be identified, perhaps because professionals do not have the training to understand babies’ cues and risks in the early relationship. Babies express their distress in a variety of ways, sometimes these are wrongly interpreted as ‘just behaviour’ or individual differences (such as being thought of as placid or “good” when in fact their normal responses have been dampened by distress). It can be hard for professionals without sufficient training to understand the subtle differences between a thriving infant and one whose behaviour and cues are showing us that they are experiencing ongoing distress from difficult relationships. It is not uncommon for adults only to take note of a child’s behaviour once they enter nursery or even school, by which time early maladaptive patterns of relating may be becoming prominent and important opportunities for early intervention have been missed

- Increasingly-stretched services may require service users to meet certain thresholds, such as having a diagnosis or getting a particular score in a clinical measure to access a service. This can exclude babies whose mental health needs must be understood in a different way, often through understanding the parent-infant relationship

- When services are very stretched, there can be pressure to prioritise cases which are perceived to be more urgent, such as older children who are exhibiting disruptive or harmful behaviour.

Babies in crisis are easily overlooked. Missed opportunities to step in when there are problems in a babies’ early relationships can have a pervasive impact on child development, which may manifest later as problems in language development, behaviour and mental health. These problems can contribute to the mental health problems of children who present to CAMHS at a later stage.

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams can drive systems change

Work with babies requires a whole-system approach, with practitioners equipped in specific skills and leaders equipped with relevant knowledge. Parent-infant relationship teams can help to create effective systems and lead workforce training. These teams work at clinical and systems-change levels.

As well as offering high-quality therapeutic support for families experiencing severe, complex and/or enduring difficulties in their early relationships, they are also expert advisors and champions for all parent-infant relationships, driving change across their local systems and empowering professionals to turn families’ lives around.

Families’ needs and situations are varied and complex and a whole range of services and policies are required to support parent-infant relationships.

Work to protect and promote parent-infant relations is different to work with older children. It is skilled work that requires specialist expertise rarely developed through core training in health and social care. Parent-infant teams have this expertise and can help others in their local system to develop it.

Specialised parent-infant work requires an understanding of very early child development (including brain development and attachment theory), the ability to read babies’ pre-verbal cues and to understand when they are showing distress or the signs of early emotional difficulties. It also requires being able to understand and work with early relationships, helping parents to overcome difficulties, identifying and promoting existing strengths and building parents’ capacities to provide the sensitive, responsive and appropriate care that their babies need to thrive.

A well-functioning whole system approach to supporting parent-infant relationships might be similar to one to prevent the harm caused by cancer. Public policies and universal services must address risk factors, such as social determinants of health and wellbeing. Universal services, such as health visiting and midwifery, can promote healthy behaviours for everyone, prevent and detect problems.

And when problems emerge, families need timely access to specialised parent-infant relationship teams who can address problems early to prevent more pervasive or longer-term harm being caused. Specialised parent-infant relationship teams can catalyse this systemic change.

Downloads

Footnotes

[1] Center on the Developing Child (2010). The Foundations of Lifelong Health (InBrief). Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-the-foundations-of-lifelong-health/

[2] Center on the Developing Child (2007). The Science of Early Childhood Development (InBrief). Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd/

[3] National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2005/2014). Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain: Working Paper No. 3. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2005/05/Stress_Disrupts_Architecture_Developing_Brain-1.pdf

[4] National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2004). Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships: Working Paper No. 1. Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/wp1/

[5] Goodman, JH (2019) Perinatal depression and infant mental health. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(3): 217-224. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883941718303984

[6] Coburn, S.S., Luecken, L.J., Rystad, I.A. et al. Matern Child Health J (2018) 22: 786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2448-7, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10995-018-2448-7

[7] Adamson, B., Letourneau, N. & Lebel, C (2019). Corrigendum to prenatal maternal anxiety and children’s brain structure and function: A systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 253: 456. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165032718311340

[8] Ou, X., Thakali, K. M., Shankar, K., Andres, A., & Badger, T. M. (2015). Maternal adiposity negatively influences infant brain white matter development. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 23(5), 1047–1054. doi:10.1002/oby.21055 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4414042/

[9] Dismukes, A. R., Shirtcliff, E. A. & Drury, S. C. (2019) Genetic and epigenetic processes in infant mental health. pp. 63-80 in: Zeanah, C. H. (Ed.) (2019) Handbook of Infant Mental Health (4th Edition). New York: The Guilford Press.

[10] Fitzgerald, H. E., Puttler, L. I., Mun, E. Y., & Zucker, R. A. (2000) Prenatal and postnatal exposure to parental alcohol use and abuse. pp. 123-159 in: Osofsky, J. D. & Fitzgerald, H. E. (Eds). WAIMH Handbook of Infant Mental Health. Vol. 4. Infant Mental Health in Groups at High Risk. New York: John Wiley & Sons

[11] See Faa et al (2016) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/bdrc.21139 for an example

[12] Lee & Kisilevsky (2014) in Chapter 9 of Fruholz & Belin (2019). The Oxford Handbook of Voice Perception. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=-Yx8DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA191&dq=fetal+voice+preference+mother +father&ots=iZLo19ddqX&sig=kCghI7tGL9HCVCtWWp31qw1R7Y0#v=onepage&q=fetal%20voice%20preference%20mother%20father&f=false

[13] Parade, S., Newland, RP., Bublitz, MH., & Stroud, LR. (2019) Maternal witness to intimate partner violence during childhood and prenatal family functioning alter newborn cortisol reactivity. Stress, 22:2, 190-199, DOI: 10.1080/10253890.2018.1501019

[14] See Tronick, E. (1989). Emotions and Emotional Communication in Infants. American Psychologist, 44(2):112-9. DOI:10.1037//0003066X.44.2.112

[15] See Bowlby, J. (2005). A secure base. Routledge, London. ISBN: 9780203440841

[16] Department for Education (2018). Improving the home learning environment. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-the-home-learning-environment

[17] Cabrera, N. J., Karberg, E., Malin, J. L., & Aldoney, D. (2017). The magic of play: low‐income mothers’ and fathers’ playfulness and children’s emotion regulation and vocabulary skills. Infant mental health journal, 38(6), 757-771.

[18] Center on the Developing Child. Toxic Stress. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/

[19] Hambrick, EP., Crawner, TW. & Perry, BD. (2019). Timing of Early-Life Stress and the Development of Brain-Related Capacities. Front. Behav. Neurosci., 13:183. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00183. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00183/full

[20] Anda, R.F., Felitti, V.J., Bremner, J.D. et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci., 256: 174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

[21] Holman, DM., Ports, KA., Buchanan, ND., et al (2016). The Association Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Risk of Cancer in Adulthood: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Pediatrics, 138 (1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4268L

[22] Danese, A., Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Milne, B. J., Polanczyk, G., Pariante, C. M.,Caspi, A. (2009). Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 163(12), 1135–1143. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214

[23] Hobson, P. (2002) The Cradle of Thought: Exploring the Origin of Thinking. p180. London: Macmillan.

[24] Barlow, J., Schrader-McMillan, A., Axford, N., et al. (2016). Review: Attachment and attachment-related outcomes in preschool children – a review of recent evidence. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 21 (1): 11-20 http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/camh.12138 https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30622993.pdf

[25] Fearon, P. (2018). Attachment Theory: Research and application to policy and practice. Transforming Infant Wellbeing: Research, Policy and Practice for the First 1001 Critical Days. Leach, P (Ed). Routledge, Oxford. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=L6QzDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT53&dq=impact+of+disorganised+ attachment+&ots=E53IJc0n2f&sig=aBK42tFLIWQBRqYzNO4LhCYUkIg#v=onepage&q=impact%20of%20disorganised%20attachment&f=false

[26] Green, J. & Goldwyn, R. (2002). Annotation: Attachment disorganisation and psychopathology: new findings in attachment research and their potential implications for developmental psychopathology in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(7): 835-436.

[27] Van Ljzendoorn, MH., Schuengel, C. & Bakermans-Kranenburg, MJ. (1999). Disorganised attachment in early childhood: Metaanalysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology, 11: 225-249 https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/1530/168_212.pdf?sequence=1

[28] Pp3-5, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG26/documents/childrens-attachment-final-scope2

[29] Levy, T.M. and Orlans, M. (2014) Attachment, Trauma, and Healing: Understanding and Treating Attachment Disorder in Children, Families and Adults. https://www.jkp.com/uk/attachment-trauma-and-healing-2.html

[30] Quote widely attributed to Frederick Douglass but original source unknown.

[31] Green, J. & Goldwyn, R. (2002). Annotation: Attachment disorganisation and psychopathology: new findings in attachment research and their potential implications for developmental psychopathology in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(7): 835-436.

[32] Coan, JA. (2008). Towards a Neuroscience Attachment. From The Handbook Of Attachment: Theory, Research, And Clinical Implications. Jude Cassidy And Philip R. Shaver, Eds. 2nd Edition Pages 241 - 265 The Guilford Press, NY. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/James_Coan/publication/230669685_Toward_a_Neuroscience_of_Attachment/links/0fcfd502d39a581d8e000000.pdf

[33] Coan, J. (2010). Adult attachment and the brain. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2):210-217. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230676787_Adult_attachment_and_the_brain

[34] Hambrick, EP., Crawner, TW. & Perry, BD. (2019). Timing of Early-Life Stress and the Development of Brain-Related Capacities. Front. Behav. Neurosci., 13:183. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00183

[35] National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2005/2014). Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain: Working Paper No. 3. Updated Edition. From http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

[36] Chowdry, H. & Fitzsimons, P. (2016). The Cost of Late Intervention. Early Intervention Foundation. https://www.eif.org.uk/files/pdf/cost-of-late-intervention-2016.pdf

[37] Moullin, S., Waldfogel, J., & Washbrook, E. (2014). Baby Bonds: Parenting, Attachment and a Secure Base for Children. Sutton Trust.

[38] National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2005/2014). Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain: Working Paper No. 3. Updated Edition. Retrieved from http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

[39] NHSE (2014). Model Child and Adolescent Mental Health Specification for Targeted and Specialist Services (Tiers 2 and 3). https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/mod-camhs-tier-2-3-spec.pdf

[40] Heckman, J. The economics of human potential. https://heckmanequation.org/

[41] WHO, UNICEF and the World Bank (2018). Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/child/nurturing-care-framework/en/

[42] Cabinet Office/DHSC (2019) Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s – consultation document https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s-consultation-document

[43] House of Commons Science and Technology Committee (2019). Evidence-based early years intervention. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmsctech/506/506.pdf

[44] NHS England (2019). Long Term Plan. Page 50. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-term-plan/

[45] Welsh Government (2017). Prosperity for All: The National Strategy. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2017-10/prosperity-for-all-the-national-strategy.pdf

[46] Scottish Government, Getting It Right For Every Child. https://www.gov.scot/policies/girfec/

[47] Scottish Government (2009). Early Years Framework. https://www.gov.scot/publications/early-years-framework/

[48] Scottish Government Programme for Government 2019-20. https://www.gov.scot/publications/protecting-scotlands-future-governments-programme-scotland-2019-20/pages/7/

[49] https://www.pmhn.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/PMHN-Needs-Assessment-Report.pdf

[50] Public Health Agency (2016). Infant Mental Health Framework for Northern Ireland. https://www.publichealth.hscni.net/publications/infant-mental-health-framework-northern-ireland

[51] Benoit, D., Parker, K. C., & Zeanah, C. H. (1997). Mothers’ representations of their infants assessed prenatally: Stability and association with infants’ attachment classifications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(3), 307-313.

[52] Branjerdporn, G., Meredith, P., Strong, J., & Garcia, J. (2017). Associations between maternal-foetal attachment and infant developmental outcomes: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(3), 540-553.

[53] Department of Health (2012) Preparation for Birth and Beyond: A resource pack for leaders of community groups and activities. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/preparation-for-birth-and-beyond-a-resource-pack-for-leaders-of-communitygroups-and-activities

[55] Hogg, S. (2019). Rare Jewels Specialised Parent-Infant Relationship Teams. Parent Infant Partnership UK. https://parentinfantfoundation.org.uk/our-work/campaigning/rare-jewels/

[56] Geddes, H. (2006) Attachment in the Classroom: the links between children’s early experience, emotional wellbeing and performance in school. London: Worth Publishing.

[57] Bergin, C. and Bergin, D. (2009) Attachment in the Classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 21, 141-170.

[58] Siegel, D. (2012) The Developing Mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. New York: Guildford Press.

[59] Feinstein, L (2015) Social and Emotional learning: skills for life and work. Early Intervention Foundation

[60] Feinstein, L (2015) Social and Emotional learning: skills for life and work. Early Intervention Foundation

[61] Gratz, KL. (2006) Risk Factors for and Functions of Deliberate Self‐Harm: An Empirical and Conceptual Review. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 10(12): 192-205.

[62] Kliewer, W., Cunningham, JN., Diehl, R. et al (2004) Violence Exposure and Adjustment in Inner-City Youth: Child and Caregiver Emotion Regulation Skill, Caregiver–Child Relationship Quality, and Neighborhood Cohesion as Protective Factor. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 33:3, 477-487, DOI: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_5

[63] Sitnick, SL., Galàn, CA., & Shaw, DS (2018). Early childhood predictors of boys’ antisocial and violent behavior in early adulthood. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40(1): 67-83. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/imhj.21754

[64] Department for Education (2018) Improving the home learning environment. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-the-home-learning-environment

[65]. Fraiberg, S., Adelson, E., & Shapiro, V. (2003). Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. Parent-infant psychodynamics: Wild things, mirrors and ghosts, 87, 117.

[66] Yoshikawa, H., Aber, JL. & Beardslee, W. (2012). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224956205_The_Effects_of_Poverty_on_the_Mental_Emotional_and_Behavioral_Health_of_Children_and_Youth_Implications_for_Prevention

[67] Feinstein, L (2015) Social and Emotional learning: skills for life and work. Early Intervention Foundation

[68] Moullin, S., Waldfogel, J., & Washbrook, E. (2014). Baby Bonds: Parenting, Attachment and a Secure Base for Children. Sutton Trust.

[69]. Zeanah, CH., Danis, B., Hischberg, L. et al (1999). Disorganized attachment associated with partner violence: A research note. Infant Mental Health Journal, 20(1): 77-86.

[70] Van IJzendoorn, M., Schuengel, C. & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. (1999) Disorganized attachment in early childhood: A metaanalysis of precursors, concomitants and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 225-249

[71] Miles, A (2018). A Crying Shame. A report by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner into vulnerable babies in England. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/A-Crying-Shame.pdf

[72] Miles, A (2018). A Crying Shame. A report by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner into vulnerable babies in England. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/A-Crying-Shame.pdf

[73] Skovgaard, A. M. (2010). Mental health problems and psychopathology in infancy and early childhood. Dan Med Bull, 57(10), B4193.

[74] Children’s Commissioner (2019) Childhood vulnerability in England 2019. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/publication/childhood-vulnerability-in-england-2019/

[75] Department for Education (2019) Statistics on pupils who are excluded from school. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/statistics-exclusions

[76] Hogg, S. (2019). Rare Jewels: Specialised Parent-Infant Relationship Teams. Parent Infant Partnership UK. https://parentinfantfoundation.org.uk/our-work/campaigning/rare-jewels/

This chapter is subject to the legal disclaimers as outlined here.

This chapter is correct at the time of publication, 1st October 2019, and is due for review on 1st January 2021.