Chapter contents

Chapter summary

This chapter of the Parent-Infant Foundation toolkit provides a guide to where specialised parent-infant relationship teams fit strategically and what outcomes they can deliver. There is a description of the various commissioning arrangements currently supporting teams around the UK, including joint commissioning, fundraising and grants.

You will find our system-level Theory of Change here and this will help you think about commissioning for outcomes. In addition to this chapter, you can find template commissioning contracts in the Network section of the Parent-Infant Foundation website.

You can download this chapter as a PDF here, or simply scroll down to read on screen.

The range of work that parent-infant teams do and the impact they create

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams work at multiple levels: as experts and champions across the system, and providers of specialised therapeutic interventions. They enable local systems to offer effective, high-quality prevention and early intervention to give every baby the best start from conception onwards.

Alongside their direct work with families, teams offer specialised parent-infant relationship training, consultation and/ or supervision to build capacity in the local workforce. They are champions for early relationships and offer advice to system leaders and commissioners, working at a strategic level to support the development and effective operation of local services and care pathways.

Chapter 2 The Case for Change explains the wide range of impacts their work can have on later outcomes, including reducing the demands on other public services such as child protection, speech and language and mental health. Many parts of the local system reap the dividends of a well-functioning specialised parent-infant relationship team.

An example of a system-level Theory of Change: the impacts of specialised parent-infant relationship teams on a local system

- At least 15% of new babies experience complex or persistent relationship difficulties with their parent/carer(s). Without specialised help these unresolved problems can undermine a range of life outcomes and families may require future specialist interventions including, in the most severe cases, a child being taken into care

- Unresolved parent-infant relationship difficulties can be passed on to future generations of parents leading to inter-generational distress and additional high costs to the public purse

- The complex and persistent nature of some parent-infant relationship difficulties are beyond the scope of universal or typical early help support, and need specialised, multi-disciplinary intervention

- Frontline practitioners may lack confidence or awareness to identify early relationship problems and provide or refer families to appropriate support

- The right kind of specialised help may not be available locally

- Local leaders, including commissioners, may be unaware of the importance of parent-infant relationships or face a lack of local strategic co-ordination in supporting the work

- A variety of direct therapeutic work to address and improve the difficulties in the parent-infant relationship

- Training, consultancy and campaigning to raise public and professional awareness and improve workforce capacity to protect and promote the parent-infant relationship

- Act as “systems champions” by facilitating local networks and working with local leaders and organisations to improve awareness, co-ordination and decision-making

- Improved parent-child attunement and interaction (a direct outcome of work with families and an indirect outcome of work with other professionals)

- Improved capacity for the public and professionals to identify and support babies and their parents

- Improvements in how organisations work separately and together, so that babies can receive timely and appropriate support

- More children benefit from a sufficiently secure and nurturing relationship with at least one parent/carer

- Local cost savings as fewer children need to be referred to speech therapy, early help, children’s services, CAMHS, paediatrics, or special educational needs services for problems rooted in parent-infant relationships

- More children experience better social, economic, physical and mental health outcomes across the lifecourse

- Fewer children move into the Looked After system

- Fewer children need mental health support as older children or adults for attachment-related difficulties

- Fewer families experience the transmission of parent-infant relationship difficulties into the next generation

Commissioning for outcomes

The system-level Theory of Change shows the short-, medium- and long-term outcomes[1] that a parent-infant team can generate.

An example of a clinical-level Theory of Change about the impacts on individual families can be found in Chapter 4 Clinical Interventions and Evidence-Informed Practice.

Commissioning arrangements

England

Commissioning of services for young children in England is currently complex and fragmented, and varies locally:

- Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) commission maternity, mental health (where there might be different funding streams for adults, children’s and perinatal mental health services) and some other areas of NHS children’s health services

- Within local authority children’s services, there can be different funding streams for the early years (which might include children’s centres) and child protection services (which might include both early help and children’s social services)

- Health visiting is funded from the local authority public health budget, which should also be used to fund the wider Healthy Child Programme and other aspects of children’s population health

- Adult services, such as those for alcohol, substance misuse, mental health and domestic violence can be funded by local authorities and/or CCGs depending on

- The nature and scope of the services. These services will be seeing adults who are parents, and commissioners may be thinking about additional support for them in this role

- NHS England funds GP services and Mother and Baby inpatient Units (MBUs)

Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) are clinically-led statutory NHS bodies responsible for the planning and commissioning of health care services for their local area. These are led by GPs and other clinicians and commission for a population of, on average, 250,000 people.

Since 2015, many CCGs have worked together in Sustainability and Transformation Plan (STP) partnership areas, together with local authorities, to develop ‘place-based plans’ for the future of health and care services in their area. STPs are five-year plans covering all aspects of NHS spending in England.

Forty-four partnership areas have been identified as the geographical ‘footprints’ on which the plans are based, with an average population size of 1.2 million each.

CCGs are currently undergoing significant changes in structures and arrangements, with mergers and the development of Integrated Care Systems (ICS) across larger footprints, typically larger than upper tier and unitary local authorities. ICSs are a new type of even closer collaboration which has evolved from an STP partnership.

NHS organisations, in partnership with local councils and others, take collective responsibility for managing resources, delivering NHS standards, and improving the health of the population they serve. Some areas already have an ICS, and the NHS has committed to there being ICSs across the whole of England by April 2021.

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams support outcomes which align to strategic priorities

Child development at 2/2.5 years, including language development School readiness Child wellbeing Emotional wellbeing of looked after children

Child development at 2/2.5 years, including language development

School readiness

Child wellbeing

Number of children entering care Informed and timely decisions about permanency Breakdowns in fostering and adoption Emotional wellbeing of looked after children

Provision of MH services for all 0-18 year olds who need them

Reduced mental health problems in older children

Wellbeing of parents and their children

The NHS Long Term Plan states:

“ICSs will have a key role in working with Local Authorities at ‘place’ level and through ICSs, commissioners will make shared decisions with providers on how to use resources, design services and improve population health (other than for a limited number of decisions that commissioners will need to continue to make independently, for example in relation to procurement and contract award). Every ICS will need streamlined commissioning arrangements to enable a single set of commissioning decisions at system level. This will typically involve a single CCG for each ICS area. CCGs will become leaner, more strategic organisations that support providers to partner with local government and other community organisations on population health, service redesign and Long-Term Plan implementation”.

ICSs will agree system-wide objectives with the relevant NHS England/NHS Improvement regional director and be accountable for their performance against these objectives. This will be a combination of national and local priorities for care quality and health outcomes, reductions in inequalities, implementation of integrated care models and improvements in financial and operational performance”[2] .

Alongside this, Primary Care Networks (PCNs)[3] are being developed. Each PCN will have a medical director (a GP). NHS England (March 2019) describes PCNs as:

“Groups of general practices working together with a range of local providers, including across primary care, community services, social care and the voluntary sector, to offer more personalised, coordinated health and social care to their local populations. Networks would normally be based around natural local communities typically serving populations of at least 30,000 and not tending to exceed 50,000. They should be small enough to maintain the traditional strengths of general practice but at the same time large enough to provide resilience and support the development of integrated teams.”

Health and Wellbeing Boards (HWBs) are established by local authorities to bring together representatives from health, social services and the local community to understand and meet the public health needs of the local population in an integrated and holistic way. HWBs bring together the directors of adult social services, children’s services and health from the local authority, together with CCG representatives. HWBs have statutory responsibility for producing Joint Strategic Needs Assessments and Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies, which assess the health and social care needs of the local population and lay out strategies for how these will be addressed.

HWBs give local government a key role in coordinating local health and care services. The future role of HWBs is somewhat uncertain, given the growth of STPs and ICSs. HWB’s have the same footprint as upper tier and unitary local authority.

Many CCGs, HWBs, ICSs will have small sub-groups with a focus on issues such as maternity, mental health and children. The emphasis on these areas and the priorities for action vary greatly by area. In some places, the First 1001 days might be a local priority, making it easier to make the case for investment in parent-infant relationship teams.

In addition to the structures set out above, some areas still have children’s trusts in place. The Children’s Act 2004 required local authorities to set up children’s trusts, which brought together a range of local agencies (many of whom had a statutory duty to cooperate). The statutory duties underpinning children’s trusts were removed in 2010, but some areas still have similar structures in place, often reporting to the HWB.

Other organisations and structures to be aware of include:

- NHS England The national body responsible for overseeing the commissioning of health services by CCGs. Also commissions certain services directly

- Public Health England Executive agency providing expertise and information to public health teams in local authorities and the NHS

- Regional commissioning support units Providers of commissioning support services to NHS commissioners

- Healthwatch Responsible for engaging with users of health and social care services and ensuring their views are heard

- Strategic clinical networks Region-based networks of commissioners, patients and providers which ensure a strategic approach to improving quality of care in priority clinical areas

- Clinical senates Comprised of a steering group and broader forum of experts to provide strategic advice to commissioners in their local area[4]

Public Health England have added localised reports about the mental health of women during pregnancy and of infants to their Fingertips database. These reports provide data that has been designed to support local needs assessment and commissioning to improve health and wellbeing.

You may like to have a look at how your area is doing by searching at: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/child-health-profiles/ data#page/13/gid/1938133228/pat/6/par/E12000005/ati/102/are/E10000031

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland has a Health and Social Care Board, and five local Health and Social Care Trusts which are responsible for both health and social services, including children’s services.

In Northern Ireland, work to promote infant mental health is being led by the Public Health Agency who developed the Infant Mental Health Strategic Framework in 2016 [5] referred to in Chapter 2 The Case for Change.

Wales

In Wales, there are seven local Health Boards and twenty-two local authorities. Health Boards play a similar role to CCGs in England, with responsibility for commissioning most health services for the local population.

Children’s services sit within local authorities. Public Health Wales are leading work with a group of stakeholders to make the case for the emotional wellbeing of babies, which they plan to make a central part of the First 1000 Days framework which will be published later this year.

Scotland

In Scotland, fourteen regional Health Boards have responsibility for planning and delivering health services for their local area, and Health Board and Local Authorities have a joint duty under the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 to integrate planning of children’s services.

Recent legislation has encouraged and enabled increased integration of services in Scotland, and thirty-one Integration Joint Boards (IJBs) have been established across the country to integrate plans and budgets [6] . The specific areas of children’s services that have been devolved to integration authorities varies between areas, but all hold strategic responsibility for some aspect of children’s health and children’s social work services.

It may vary from area to area whether NHS Boards, Local Authorities or Integration Joint Boards take the lead for the first 1001 days and infant mental health. [7]

In 2017, the Perinatal Mental Health Network for Scotland, a national managed clinical network was established. The network has undertaken a range of work including undertaking needs assessment, making service recommendations and launching a curricular framework for maternal and infant mental health.

Chapter 2 The Case for Change includes information about national policies relevant to commissioning services which ensure the emotional wellbeing of babies.

Commissioning specialised parent-infant relationship teams: the ideal

Ideally, specialised parent-infant relationship teams should not be commissioned in isolation, but as part of a wider strategy that secures a pathway of support for babies and their families in the local area. This ensures support for families with differing levels of need, so that parent-infant teams can focus on the most appropriate families for their service and are able to refer families who do not need such intensive support to other services.

The range of work undertaken by specialised parent-infant relationship teams, together with the complex commissioning arrangements currently in place, means that parent-infant teams can legitimately be funded from a range of sources.

Ideally parent-infant teams should be jointly funded by CCG Children and Young People’s Mental Health commissioners (recognising their role in supporting the mental health of the youngest children), by local authority children’s services (recognising their role in supporting development in the early years, and in tackling problems in parenting and family functioning that might otherwise lead families in the child protection system), and by local authority public health budgets (recognising their role in child health and mental health promotion), perhaps also with contributions from maternity and adult services and other public services such as the Police and Crime Commissioner.

Such pooling of resources enables the development of a strong, sustainable team that can work with professionals across the system to ensure babies at risk are safe, healthy and developing well.

Partnership working and joint commissioning arrangements need clear accountability. Our Rare Jewels report (2019) identified that there is confusion about where responsibility for commissioning parent-infant relationship services should sit.

We have argued that there should be a lead accountable commissioning body for all children’s mental health services (including those for infants).

Commissioning specialised parent-infant relationship teams: the reality

Some of the parent-infant teams in the UK, such as the Anna Freud Centre team and OXPIP, have been around for over 20 years. New teams are being commissioned around the country and we are pleased to see the number of services growing.

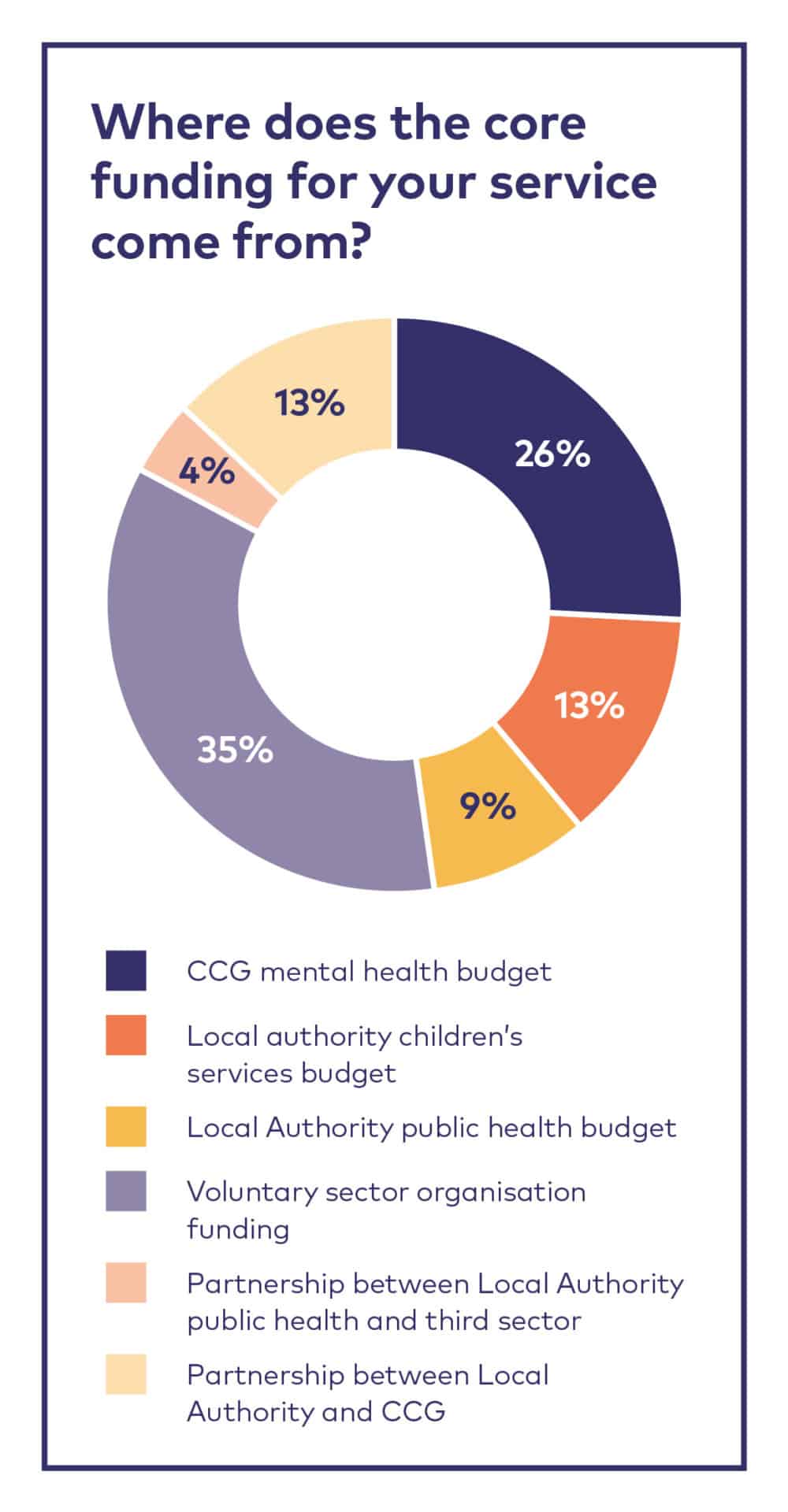

The funding and drive to establish the existing parent-infant teams has come from many different places: the voluntary sector, early years or child protection teams or public health within local authorities, and/or maternity, adult mental health and children and adolescent mental health budgets within CCGs (and their equivalents in the devolved nations).

In a survey of parent-infant teams, 21 services told us where they got their core funding from.

Interviews with commissioners in Leeds, Tameside and Glossop and Croydon illustrate the importance of the following themes in setting up and sustaining a specialised parent-infant relationship team:

- Local leaders having a good understanding of the First 1001 days, why early relationships matter and driving change

- Strategic commitment to giving children the best start in life and a whole-system approach to achieving this goal

- Partnership working between commissioners and between services

- Flexibility, persistence and seizing opportunities to grow and develop services

Examples of existing commissioning arrangements

The Infant Mental Health Service started from an intervention offered by health visitors in children’s centres. Seeing the value of this work, commissioners made infant mental health part of the CAMHS service specification to ensure a clear, consistent offer across the system. The service is funded by the Local authority public health budget and the CCG Children and Young People’s mental health budget.

The Health and Wellbeing Strategy in Leeds has ‘giving children the best start in life’ as a key priority, and there is clear strategic leadership for the early years in the city, as well as good partnership working between organisations to deliver this.

The Best Start PIP team is commissioned by the local authority. The team is part of Croydon Best Start, a local initiative to combine fully health and local authority services for children from pregnancy to five.

Launched In 2016, Croydon Best Start brings together midwifery, health visiting, services for children and families provided by Croydon Council and the voluntary sector.

The PIP team is seen as part of the local offer to address adverse childhood experiences and to support nurturing relationships in order to give all children the Best Start.

The Early Attachment Service is funded by public health and the CCG Tameside and Glossop areas are part of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, which has prioritised perinatal and infant mental health and all children starting school “ready to learn”. To deliver this, the authority is working to integrate services for children and families from birth to when they start school.

Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership have identified parent and infant mental health as a key transformation priority and are looking at the work of the whole system including setting up new parent-infant services, perinatal mental health services and IAPT services for parents of babies in each borough.

These services work closely together and integrate with existing universal and specialist services that work with families. Manchester has prioritised both perinatal and infant mental health, using new funding from NHS England and investing additional funds in each of the 10 boroughs.

This has provided an opportunity to roll out the Early Attachment Service to other boroughs, which the Tameside and Glossop team are supporting.

Rare Jewels: Specialised Parent-Infant Relationship Teams in the UK

In 2019, PIP UK completed the first comprehensive survey of parent-infant relationship team provision across the UK [9] . This report found that there is very little mental health provision for children aged two and under. Most babies in the UK live in an area where there is no parent-infant relationship team; our research found only twenty-seven multi-disciplinary, free at the point of delivery parent-infant relationship teams in the UK.

Despite child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) nominally being a service for 0-18 year olds, data collected through Freedom of Information requests suggested that in some areas, commissioners do not commission any mental health services at all for young children. Forty-two percent of CCG areas in England CAMHS services do not accept referrals for children aged two or under. Provision is also limited in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Rare Jewels discusses why this might be the case.

All areas in England have had to produce a Children and Young People’s Transformation plan to indicate their ambitions to achieve the aims of the Future in Minds strategy document. This has now moved on to the NHS Long Term Plan [10] (LTP, January 2019) which continues the focus on children’s mental health. The LTP states:

“Over the coming decade the goal is to ensure that 100% of children and young people who need specialist care can access it”.

Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) or Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) are required to develop and agree strategic five-year plans by mid-November 2019 which set out how they will deliver the commitments made in the Long-Term Plan. The plans should include information about what local systems are doing to improve prevention and how they are expanding children and young people’s mental health services in line with the LTP commitments.

As set out in the Rare Jewels report (2019), we believe that achieving the LTP commitments for the youngest children requires adequately resourced specialised parent-infant relationship teams in all localities. A traditional CAMHS model and interventions may not meet the needs of 0-2 year olds.

Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) will be receiving additional funding to deliver NHS Long Term Plan commitments, including

expansion of children and young people’s mental health services which could be used to fund parent-infant relationship services.

Therefore, a useful point for conversations with CCGs is the requirement for them to commission a service for 0-25 year olds.

The NHS Long Term Plan also has a clear focus on perinatal (adult) mental health and includes a comment on providing support for women with relationship/attachment concerns. Again, CCGs have increased funding in their baseline budgets for a range of mental health services including perinatal and most areas have a commissioner responsible for perinatal mental health.

Another potential funding route may be through Local Maternity Systems (LMS) which are responsible for delivering the Better Births [11] ambition, a five-year forward view for maternity and related services. There is usually a local programme lead working on behalf of the local CCGs across a larger footprint.

In some areas, the Chair of the local Community and Voluntary Sector (CVS) infrastructure organisation may meet regularly with CCG and Local Authority leaders and may be willing to raise suggestions and identify opportunities.

Finally, the prevention green paper [12] currently out for consultation includes emphasis on early intervention and 1001 days therefore, there may be future opportunities through public health commissioning within local government.

Sources of information which commissioners and others may find helpful:

The costs of perinatal mental health problems https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/costs-of-perinatal-mh-problems

Child health profiles

http://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile-group/mental-health/profile/perinatal-mentalhealth

Child health profiles, including mental health in pregnancy and infancy

https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/child-health-profiles

Maternity data set interactive report

https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/ data-collections-and-data-sets/data-sets/maternity-services-data-set

Children’s and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing

http://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile-group/mental-health/profile/cypmh/data

Early Years Child Health Profiles

https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/child-health-profiles/data#page/1/ gid/1938133223/pat/6/par/E12000007/ati/102/are/E09000024

What should be commissioned?

Specialised parent-infant relationships teams are ideally commissioned as an essential and fully-integrated part of the broader ecosystem that supports the emotional wellbeing of babies. This includes universal and specialist services such as health visiting, maternity, adult and perinatal mental health and the voluntary sector. The team’s system-level work should be commissioned to build skills and knowledge across the workforce so that parent-infant relationships are at the heart of the system and community.

Commissioners may decide to commission teams to cover specific CCG or local authority areas or to pool resources to create a proportionately larger team to work across a larger geographical area (which might enable some economies of scale).

What works best will depend on local factors such as geography, transport links, population need and the level of resourcing in other services in the region.

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams tend to be provided by NHS CAMHS teams, multi-disciplinary teams in public health services or children’s services, or third sector organisations. In recent years, some perinatal mental health teams have recruited workers with specialised parent-infant relationship competencies.

Teams look different across the UK but they are all multi-disciplinary with specialised expertise in supporting and strengthening the important relationships between babies and their parents or carers. Together they provide a toolbox of interventions and support for early relationships at risk or experiencing severe difficulties.

The majority have at least one clinical psychologist and one parent-infant or child psychotherapist. Other roles on the team often include:

- Family support workers or key workers

- Infant mental health practitioners/parent-infant therapists

- Specialist health visitors

- Operational managers and administrators

Some services also have practitioners such as a midwife, play therapist, family therapist, systemic therapist, occupational therapist, art therapist, baby massage teacher, social worker and/or community engagement coordinator.

Chapter 5 Setting Up a Team and Chapter 7 Recruitment, Management and Supervision contain lots of information about different professionals and the roles within teams. The section below focusses on commissioning according to local need and size of population.

Commissioning for local need

Teams should be designed so that they can support the needs of the local population.

One way to understand the level of local need for specialised parent-infant provision is to take the accepted incidence of disorganised attachment in the general population of infants and then adjust to account for local indices of need. Robust research estimates that disorganised attachment, the parent-infant relationship style most closely associated with the poorest outcomes for children, is about 15% in middle-class non-clinical groups and 34% in low-income samples [13] . This figure is greater in families where there has been, or there is a risk for, maltreatment (up to 48%), children of mothers misusing substances/alcohol (estimated at 43%), children of depressed parents (estimated at 21%) and for families coping with multiple risks [14] . The need will be even higher in communities affected by other forms of trauma, such as in Northern Ireland, refugees and asylum-seeking families or other communities particularly affected by racism or harassment, poverty, mass unemployment or traumatic incidents.

Where it exists, local survey data regarding the prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in parents may help commissioners to adjust their estimates for how many families could benefit from parent-infant work. This can only be done at a whole population or community level, not as an individual screening mechanism. For example, where previous work has established that a community has a high average ACE score, one might argue that the pressures on the parent-infant relationships in that community will be higher.

Some places are applying the ACEs research to service thresholds or to screen individual families. Their hypothesis is that a person’s number of ACEs indicates their level of need. Unfortunately, this is not supported by the latest evidence [14] : the ACEs research is based on large population-level studies, with estimates of risk only being applicable to groups not individuals. There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of ACEs in screening or referral criteria [15], [16], [17] .

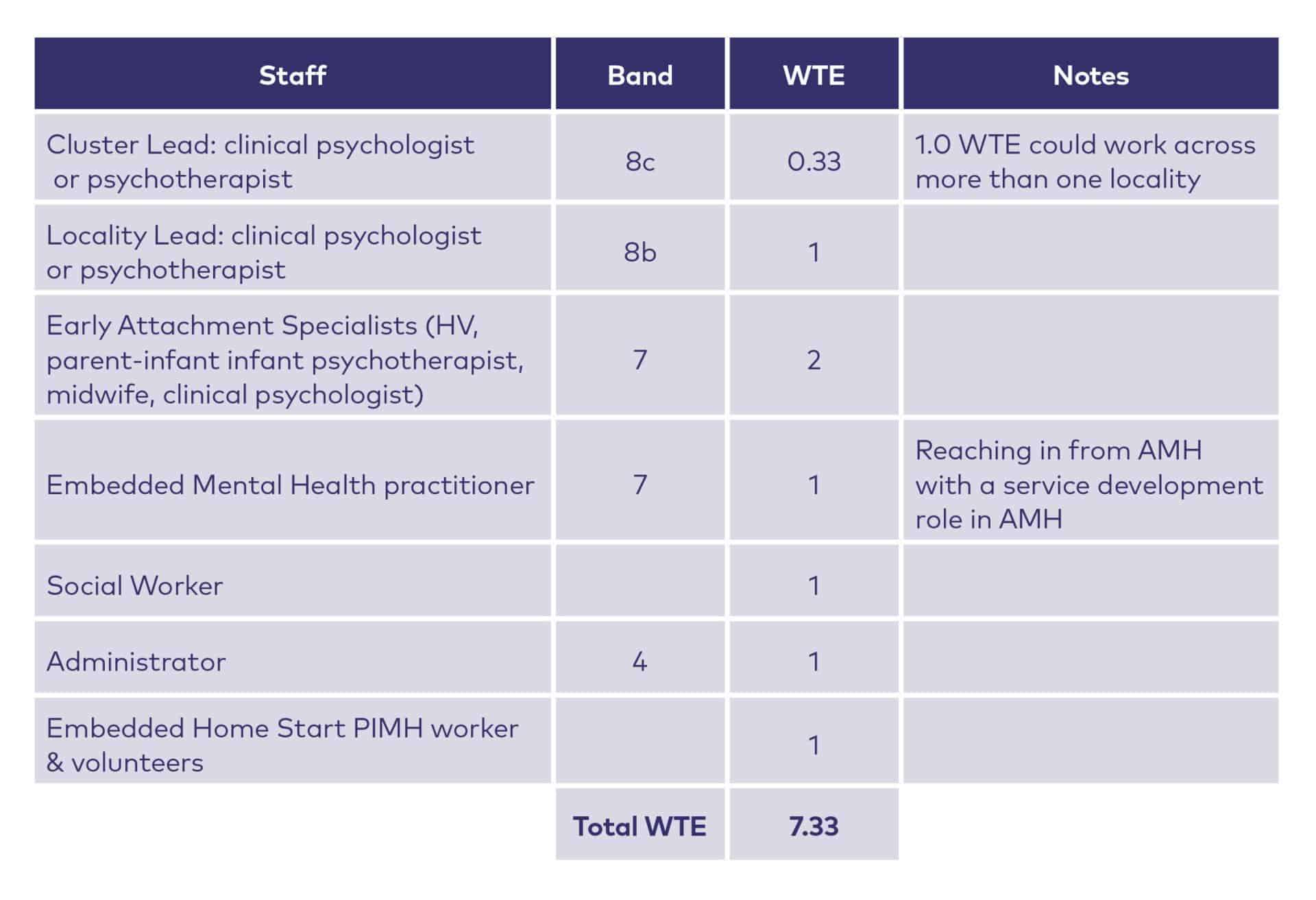

In Greater Manchester, some work has been done to understand the size of service required for population of 280,000 which equates to a birth rate of around 3300 and is roughly the size of an average local authority in England. The table below shows the suggested staffing in their service specification.

Incremental development

There is a myriad of ways to commission, fund and set up a specialised parent-infant relationship team. Many teams grow from humble beginnings. For example, the Early Attachment Service in Tameside and Glossop, a team of now 7.3WTE staff, started 13 years ago with 0.5 WTE and has grown through small, yearly increments. Chapters 5 and 6 are all about getting started, delivering services to families and becoming sustainable, but we describe briefly below some of the different ways that existing teams began to gather support and momentum locally:

1. Creating clinical leadership capacity

With agreement from strategic leads, identifying a clinical lead (typically in community services) to help think about and map local resources and identify gaps. Sometimes this starts as a ring-fenced part of an existing post and grows into something more substantive over time.

2. Creating an infant/perinatal mental health forum

These can take different forms but typically involves bringing together people from different parts of the community, professional services, commissioning and strategic development to provide a space to think about the needs of local babies and their families, to co-develop professional development activities and explore opportunities for partnership working.

Ideally, the forum is an integrated perinatal and infant mental health forum which facilitates “whole system” thinking and working.

3. Writing an infant mental health strategy

Bringing together commissioners and service leads, potentially with local service providers, the voluntary sector and community or service user reps to write a 2-3 years strategy (either an Infant Mental Health strategy or ideally an integrated Perinatal and Infant Mental Health strategy) to build on local strengths and identify key drivers and opportunities for growth.

This group may also form an infant mental health forum, or at least relate to it as its strategic body, feeding into existing governance structures.

“Once we’d got a shared infant mental health strategy that everyone could sign up to, it allowed us to create a really well co-ordinated parenting strategy.

This meant that all the parenting groups offered to families in our locality then built on the importance of parent-child relationships and sensitive attunement”.

Parent-infant team clinical lead

4. Maximising impact by enhancing existing services’ offers in the first 1001 days

There are likely to be commissioned and provided services locally which already have contact with parents and their babies. These existing services might be able to improve their offer of specialised parent-infant relationship work further through enhanced or joint commissioning and funding arrangements.

For example, a pre-birth assessment service may be able to recruit parent-infant relationship specialists to begin offering work to families about to have a baby.

In Birmingham, Ruth Butterworth, an academic psychologist from the local clinical psychology training course, saw that babies were missing from the attentions of clinicians and commissioners and so began running a twice-yearly Infant Mental Health forum.

The meetings were two hours long and had an invited speaker on clinical topics. It grew rapidly to attract a wealth of participants and provided crucial support for isolated practitioners trying to do parent-infant work in various agencies across the city.

Whilst led from a university, the forum provided a useful quality-improvement and partnership-development role.

Invitees to an IMH forum can include midwifery, health visiting, perinatal adult mental health teams, adult mental health, child mental health, social care, voluntary and third sector providers, domestic abuse organisations, substance misuse services, public health, local councillors, Family Nurse Partnerships, police, safeguardiang teams/boards, infant feeding colleagues, children’s centres and various senior service leads and commissioners.

The learning from the Birmingham example was that it was helpful that the lead was “strategically neutral” and not from one of the provider trusts as this may have led to a different dynamic.

Forums like this take a lot of time, effort and commitment which busy clinicians are generally not afforded, although having this type of clinical leadership / quality improvement activity written into local strategies can help legitimise it and develop momentum.

Developing a service within CAMHS

CAMHS may be able to develop their offer to under-twos through specialised direct work, consultation to other colleagues or training, in small ways at first but which can demonstrate ‘demand’ and impact. This supports CAMHS staff to develop some of the specialist skills required to work with the parent-infant relationship and could lead to dedicated referral pathways for children under two.

This specialised part of CAMHS should be clearly defined as a parent-infant relationship service so as not to inadvertently locate the difficulties in the infant. The focus is on the relationship and the infant’s presentation is understood as an adaptation in the context of that relationship.

In a Freedom of Information request for the Rare Jewels report (2019), 42% of CCGs reported that their mental health services do not accept referrals for under-twos.

Other sources of funding

Charitable funding

Some specialised parent-infant relationship teams operate as charities or charitable organisations, i.e. OXPIP and NorPIP, or as a programme of work within a larger third sector organisation i.e. NEWPIP within Children North East and Croydon Best Start PIP within Croydon Drop In.

Third sector organisations may be set up in a variety of formats. Detailed information about the different structures and governance options can be found at:

- https://www.gov.uk/set-up-a-charity (England or Wales)

- https://www.oscr.org.uk (Scotland)

- https://www.charitycommissionni.org.uk (Northern Ireland)

- There is also usually information available through your local Community and Voluntary Services infrastructure organisation. A list of these are available at https://navca.org.uk/find-a-member-1

- Local charitable organisations can also find advice and support on governance, fundraising, marketing, etc. through the following national bodies:

- NCVO https://www.ncvo.org.uk/

- Small Charities Coalition http://www.smallcharities.org.uk/

Charitable organisations rely on finding their own funding so usually need an in-house fundraiser or budget to pay an external fundraiser with the time, effort and expertise to source the right type of funding for the organisation and its activities.

Income typically comes from a range of sources:

- Local commissioning

Third sector organisations are often able to apply for local NHS and local authority commissioning tenders to deliver a service. The tender opportunity will stipulate the budget, the key performance indicators and the scope of the service expected to deliver these - Fundraising from trusts and foundations

There are a range of trusts and foundations that offer funding for charities providing local services. Applications for funding may be accepted on a rolling basis, during certain windows throughout the year or related to specific funding calls on themed topics. Each trust and foundation operate differently and applicants will need to familiarise themselves with each funders’ specific priorities.Things to consider include (but are not restricted to):

- Whether the funding body has stipulations around demographics of beneficiaries such as the age, gender, specific communities

- The amounts available and the typical size of grants distributed

- The time period over which grants are available i.e. one year, three years

- Whether they fund a charity of your size and income (within a specified annual turnover)

- Whether they fund core (running) costs or only certain activities

Major donors

These are typically philanthropists or companies who seek to invest in local and national charities in areas of work which align to their interests. Access to these funders often requires a warm relationship which might be generated through staff, trustees, patrons.

Evidence of impact

Funders need robust data collection and demonstration of the benefits of your work to reassure them that your work is worth investing in. There is more information in Chapter 8 Managing Data and Measuring Outcomes. The Parent-Infant Foundation can assist with this in various ways and has a bespoke data software system to support local teams in collecting data for service improvement and impact reporting.

Income generation

When charities are considering their income streams, some also include activities to generate income beyond applying for funds from elsewhere. Examples from some of the existing teams include:

- The provision of therapeutic services on a private basis (charging some clients based on a variety of criteria) or invoicing public sector services on an individual case basis

- The provision of training days or courses for other professionals, either charged for on an individual/organisational basis or commissioned at scale

- Commissioned or contractually-funded supervision or consultations

NHS and local authority teams can also establish income generation activities and these are most easily set up at the commissioning contract stage where the legal and commercial aspects can be discussed.

Community fundraising

This is income generated through fundraising activities such sponsored activities, street collections and so on. Fundraisers typically have a personal reason for supporting your charity and this might be a consideration in your fundraising strategy.

The Parent-Infant Foundation may know other people in your area looking into setting up a parent-infant relationship team, so do contact us as we may be able to put you in touch with them. We do not fundraise on behalf of local parent-infant relationship teams but can assist with discussions and thinking around fundraising and income generation.

Downloads

Footnotes

[1] In our example Theories of Change, we use “short-term outcomes” to describe the outcomes that come about during the intervention or work, such that they can be seen or measured by the end. We use “medium term” to mean after the intervention/work is finished (exactly how long depends on a number of factors including the nature of the intervention and what follow-up is planned). “Long-term outcomes” are much longer term and may relate to impact at a community or population level.

[2] NHSE (2019) Long Term Plan, page 29 https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-ter

[3] NHSE (2019) Primary Care Networks: Frequently Asked Questions https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/pcn-faqs-000429.pdf

[4] NCVO website. Health and wellbeing boards - roles and responsibilities https://knowhow.ncvo.org.uk/funding/commiss commissioning-1/influencing-commissioning-1/health-and-wellbeing-boards-1/roles-and-responsibilities

[5] Public Health Agency (2016). ‘Supporting the best start in life’ Infant Mental Health Framework for Northern Ireland. https://www.publichealth.hscni.net/sites/default/files/IMH%20Plan%20April%202016_0.pdf

[6] http://www.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefingsAndFactsheets/S5/SB_16-70_Integration_of_Health_and_Social_Care.pdf

[7] All aspects of children’s services are included in 9 Integration Joint Boards (IJBs), in 1 IJB children’s services are located with children’s primary health services and education within the council; and 21 where children’s services remain with the local authority. https://childreninscotland.org.uk/integration-of-health-and-social-care/

[8] Hogg, S (2019). Rare Jewels: Specialised Parent-Infant Relationship Teams in the UK. Parent Infant Partnership UK. https://parentinfantfoundation.org.uk/our-work/campaigning/rare-jewels/

[9] Hogg, S (2019). Rare Jewels: Specialised Parent-Infant Relationship Teams in the UK. Parent Infant Partnership UK. https://parentinfantfoundation.org.uk/our-work/campaigning/rare-jewels/

[10] NHS (2019) NHS Long Term Plan https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/

[11] NHS England (2015) The National Maternity Review https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf

[12] Cabinet Office and DHSC (2019) Open consultation. Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s – consultation document https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/advancing-our-health-prevention-in-the-2020s/advancing-our-health-preventionin-the-2020s-consultation-document

[13] Van IJzendoorn, M., Schuengel, C. & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. (1999) Disorganized attachment in early childhood: A metaanalysis of precursors, concomitants and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 225-249

[14] Cyr, C., Euser, E. M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. & Van IJzendoorn, M. (2010) Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology. 22 (1), 87-108

[15] Ford, K., Hughes, K. Hardcastle, K. et al (2019). The evidence base for routine enquiry into adverse childhood experiences: A scoping review. Child Abuse and Neglect, 91: 131-146. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014521341930095X

[16] Murphey, D & Dym Bartlett J (2019). Childhood adversity screenings are just one part of an effective policy response to childhood trauma. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/childhood-adversity-screenings-are-just-one-part-of-aneffective-policy-response-to-childhood-trauma

[17] Bateson, K., McManus, M. & Johnson, G (2019). Understanding the use, and misuse, of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in trauma-informed policing. The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles April 23. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X19841409

This chapter is subject to the legal disclaimers as outlined here.

This chapter is correct at the time of publication, 1st October 2019, and is due for review on 1st January 2021.