Chapter contents

Chapter summary

This chapter of the Parent-Infant Foundation UK toolkit will help you think about which therapeutic approaches a specialised parent-infant relationship team might offer. This might influence the types of professionals you recruit. It introduces the clinical guidance relevant to parent-infant relationship work and an example of a clinical-level Theory of Change. There are brief descriptions of some of the most popular and effective evidence-based practices in parental engagement, assessment and intervention in parent-infant relationship work. For information about mental health professions and their training, skills and qualifications see Chapter 7 Recruitment, Management and Supervision.

You can download this chapter as a PDF here, or simply scroll down to read on screen.

National clinical guidance

There are not yet any national guidance or quality standards which direct the work of specialised parent-infant relationship teams. There are recommendations relevant to the parent-infant relationship in several NICE guidance documents including Children’s Attachment (QS133), Postnatal Care (QS37, quality statement 9), Social and Emotional Wellbeing: Early Years (PH40) and Early years: promoting health and wellbeing in under 5s (QS 128).

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE.org.uk) states that securely attached children have better outcomes than non-securely attached children in social and emotional development, educational achievement and mental health. Early attachment relations are thought to be crucial for later social relationships and for the development of capacities for emotional and stress regulation, and self-control.

Children and young people who have had insecure attachments are more likely to struggle in these areas and to have emotional and behavioural difficulties (NICE, QS133). Parents and carers of children under 5 should be offered a discussion during each of the five key health visitor contacts about factors that may pose a risk to their child’s social and emotional wellbeing (NICE, QS128).

Women should have their emotional wellbeing, including their emotional attachment to their baby, assessed at each postnatal contact (NICE, QS37).

Parents or main carers who have infant attachment problems should receive services designed to improve their relationship with their baby (NICE, QS37).

Therapies offered by parent-infant teams are based on sound psychological theory, excellent scientific research and increasingly promising outcomes evidence. However, the body of evidence about the impact of different interventions on the parent-infant relationship is still developing, as is the evidence for many interventions for older children, young people and families. As the Early Intervention Foundation has explained, although the case for early intervention is very well made, the overall evidence base for the programmes available now in the UK needs further development [1].

The Early Intervention Foundation (EIF) is an independent charity and one of the Government’s ‘what works’ centres.

It champions and supports the use of effective early intervention to improve the lives of children and young people at risk of experiencing poor outcomes. Some of the parent-infant interventions described below feature in the Early Intervention Foundation’s Guidebook [2] which provides information about early intervention programmes that have been evaluated. Some programmes widely used in the UK are yet to be rated [3].

The EIF Guidebook reports two types of evidence: one about a programme’s effectiveness and the other about its cost-benefit. The Guidebook uses high-quality, often academic research such as Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) but does not yet account for the variability created by implementation factors. These are critical aspects of delivery which determine whether an intervention will actually deliver outcomes in real-world settings. For example, the world’s best-evidenced intervention will not help families if parental engagement is poor, staff are not properly trained and supervised, and the intervention is delivered in an inaccessible venue and manner. Where available, we provide a link to the relevant section of the EIF Guidebook with this caveat in mind.

There is additional analysis of infant-related interventions at the California Evidence-Based Clearing House for Child Welfare [4].

Theories of Change

“A Theory of Change lays out what specific changes the group wants to see in the world, and how and why a group expects its actions to lead to these changes.” [5]

Which clinical approaches and interventions to select is influenced by the outcomes you wish to achieve. A Theory of Change helps clarify those outcomes and which activities should achieve them. Figure 1 presents an example of a clinical-level Theory of Change which explains the therapeutic mechanism of change and intended outcomes between individual families and practitioners. In Chapter 3 Funding and Commissioning, there is an example of a system-level Theory of Change for the work of specialised parent-infant relationship teams which explains the impact teams can have at a population and system level.

Many teams develop, and ideally co-create with stakeholders, their own clinical Theory of Change to ensure that they select the most appropriate clinical approaches for their intended local outcomes. It shows what kinds of activities and essential therapeutic ingredients an intervention should contain in order to effect change for children and their parents. It should ideally be based on the research that shows trauma and adversity within the early parent-infant relationship have the potential to compromise the child’s longterm emotional, mental and physical health.

Co-creating a local Theory of Change can be a very helpful process to work through with a range of local stakeholders because it helps everyone think together about exactly what the team will and won’t be doing, how and for what exact purpose.

There is helpful guidance about co-creating a Theory of Change at NCVO Knowhow [6] and information about how Theories of Change underpin evaluation in the Early Intervention Foundation’s “10 Steps for Evaluation Success” [7] .

In our example Theories of Change, we use “short-term outcomes” to describe the outcomes that come about during the intervention, such that they can be seen or measured by the end of the intervention. We use “medium-term” to mean after the intervention is finished (exactly how long depends on a number of factors including the nature of the intervention and what follow-up is planned).

“Long-term outcomes” tend to be at a population, community or societal level.

An example of a clinical-level Theory of Change

- Decreased traumatising behaviour by the parent towards the baby, reduced sense of stress with the baby, improved parental empathy, consistency and motivation

- Parent and infant feel safe with each other, improved warmth in the interaction, improved attunement and more developmentally appropriate interactions

- Improved infant invitation and initiation of interaction with adults including parents

- Improved assessment and support of the family’s needs, child protection issues and the parent’s capacity to change

- Improvements in parent’s capacity to sustain emotional and behavioural self-regulation

- Quality of parent-child relationships for indicated child and siblings is improved

- Child is more relaxed, with improved social and emotional development

- Improvements in parents’ openness to trusting relationships with helping professionals and in the effectiveness of professional assessment and support

- Improved likelihood of child securing better physical and mental health, social, emotional, cognitive and language development

- Reduced risk of child needing referral to speech therapy, early help, children’s services, CAMHS, paediatrics, or special educational needs services for problems rooted in parent-infant relationships

- Reduced risk of transmission of parent-infant relationship difficulties into the next generation

A system-level Theory of Change explains the impact teams can have at a population and system level. A clinical-level Theory of Change explains the therapeutic mechanism of change and intended outcomes between individual families and their parent-infant practitioner.

Engagement prior to and during assessment

Your referrers are critical to parental engagement: the quality of engagement they have with the family and with you as a team influences the motivation of the family. Therefore, time spent with your referrers, building mutual understanding, offering consultations and joint visits and ensuring smooth referral paths pays dividends in terms of family engagement later down the line. Joint visits can be particularly effective in scaffolding a families’ transfer from referrer to team.

Give referrers guidance and support about how best to describe the work of the team including language to describe the work to families. Language should be strengths-based, not focussed on deficits or “fixing the problem” and small tweaks can be important. For example, after describing what the parent-infant team can offer, referrers could say to families “Is that something you’d be willing to try?”

Dialogic research shows that use of the word willing (as opposed to want, will, should etc) increases motivation to engage in services perceived to involve difficult conversations [8] .

Parents who are struggling to form a relationship with their baby commonly experience relationship difficulties in other areas of their life, including with professionals and services. Trust is at the heart of attachment. The reason that a family have been recommended to a parent-infant relationship team might be the very thing that makes it so hard for them to engage. Engaging families referred to a specialised parent-infant relationship team frequently takes skill and tenacity from sensitive practitioners but the investment in time is essential if the later work is to be effective. Home visits, texting families and joint visits may help.

Motivational interviewing may offer a promising approach to enhance families’ motivation to engage [9] . The Health Foundation produced a useful evidence scan in 2011 about how best to train professionals [10] .

Despite good evidence that the engagement of fathers is highly beneficial for children, mothers and the whole family even where parents are separated, fathers are more likely to be overlooked or inadvertently excluded by services supporting children [11] . We recommend the Dads Matter and Fatherhood Institute websites for practical advice and information about training.

Infant Massage

Some parent-infant relationships teams either include or work closely with infant massage practitioners. Those teams tell us that infant massage can be a useful vehicle through which parents can be identified and supported to engage with a specialised parent-infant relationship team, or as a useful step down or step out offer. Infant massage is typically viewed by parents as a non-threatening, enjoyable experience, which can be a time to build trust with helping professionals and spend quality time learning how to interact sensitively with their very small baby.

Infant massage comes in different forms and quality varies. Good quality infant massage focusses on the infant’s needs for sensitivity and attunement [12] to ensure it does not create an opportunity of relational harm for the baby. Where a parent or carer is coached in how to massage their infant’s skin gently and calmly, this is reported to help babies to feel secure and improve emotional regulation such that crying and emotional distress are reduced, and relaxation and sleep are improved [13] . For parents, infant massage is reported to improve feelings of closeness to the baby and improve attunement through a deeper understanding of the baby’s cues and responses, possibly aided by both the baby and parent experience an increase in oxytocin [14] .

The intervention outcomes evidence about infant massage is mixed. The EIF Guidebook reports that the outcomes evidence does “not currently support the use of infant massage with low-risk groups of parents and infants”. Additional evidence suggests that infant massage could potentially make things worse for mothers and infants whose relationship was observed to be ‘at risk’”. However, EIF go on to say “if the activity is safe, relatively inexpensive and commissioned primarily because local families want and enjoy it — then there is likely no harm in making it available to parents and children, or for communities to commission it for themselves. However, if the activity is being offered to improve outcomes that it has little evidence of achieving then commissioners should think twice about why and for whom they are commissioning it, particularly when resources are very tight.”

There may be more promising effects on the interaction where mothers are moderately depressed. A meta-analysis of approaches to enhance depressed mothers’ sensitivity revealed that ‘the most effective and robust technique to improve maternal sensitivity… was the use of baby massage’ [15] and this study, which had strict inclusion criteria, in fact found no evidence that individual interpersonal therapy for depressed mothers had any effect on sensitivity. However, the evidence suggests that baby massage has the most effect when applied to medium-risk mothers with little or no positive results for low- or high-risk families [16] . Baby massage with depressed mothers has been shown to increase their capacity to recognise emotional expressions, including negative ones, and be more accurate in affective language communication [17] .

Practitioner's Perspective on Infant Massage

“I have been part of the Parent Infant Mental Health Service programme delivered by Surrey NHS for more than 12 years, providing infant massage teacher training to health visitors, nursery nurses and local children’s centre staff.

The specialist health visitors tell me that it has proved to be one of the most helpful and positive parts of the programme and they do not want to lose it.

Infant massage is always part of a ‘whole child’ viewpoint, whether as an enhancement to everyone’s parenting or as a help for those parents identified as struggling.

For those parents who have not received close care in their own infancy and childhood and who may never have formed a close bond with their own mothers and fathers, infant massage can be a simple and enjoyable way to help them discover a new relationship with their baby.

Infant massage can be “a welcoming first step across the threshold” and is relatively inexpensive. Once inside the children’s centre, the other resources and support on offer become accessible. This is especially true of families who may face a host of barriers, including poverty and ongoing mental health issues.

I believe that the training process is primarily about enabling the parent to tune in to their own sensitivity so that they can carry out this simple skill with confidence and enjoyment.”

Sally Cranfield, Massage for Babies

Assessment

All qualified children’s health and social care professionals are trained to conduct a thorough assessment of a family’s needs. Differences in emphasis and approach bring an advantageous multi-disciplinary aspect to team working. It is useful for team colleagues to acknowledge and articulate what helpful differences exist between them, as well as what is core to their unified approach.

Like treatment approaches, assessments should be tailored to the family’s particular needs and presentation. Parent-infant assessments typically include:

- Information provided by a referrer or other professional

- A semi-structured conversation with the family to hear about their concerns

- A direct observation of the parent-infant interaction by the practitioner

- Questionnaires, interview or assessment methods which enhance understanding of particular aspects of the infant’s experience, such as reflective functioning, adult mental health questionnaires, parental emotional regulation and infant social and emotional development.

Ideally, an initial assessment of a families’ needs provides both critical clinical information and important baseline data for future outcomes monitoring. If the team is required to report against certain standard outcomes or they are part of a research trial, what is collected for clinical purposes is then enhanced through additional baseline measures.

Detailed information about how to measure outcomes and a comprehensive table of assessment tools is found in Chapter 8 Managing Data and Measuring Outcomes. The section below focusses on the composite elements of a robust clinical assessment.

Tools to support clinical assessment

Chapter 8 Managing Data and Measuring Outcomes includes comprehensive tables of assessment questionnaires and measurement tools, including the age range with which they can be used. There is further information about assessment tools in Appendix 2 of Conception to Two: Age of Opportunity (2013). We highlight below a few selected tools which have been used by the nine PIP [18] teams.

The Ages and Stages Questionnaire Social and Emotional – 2nd edition (2015)

The ASQ:SE2 (www.agesandstages.com) is a parent-completed questionnaire about their baby that covers communication, gross and fine motor skills, problem solving and personal-social skills. It identifies social and emotional issues for the baby including self-regulation, communication, autonomy, compliance, adaptive functioning, affect and interaction with people.

The ASQ:SE2 can be used to demonstrate that the infant has attained, or remained on, an acceptable pathway of social and emotional development in a situation when this might be jeopardized. Optional training is available from www.brookespublishing.com. In 2019, prices are: starter kit US$295, user guide $55, DVD $50.

Keys to Interactive Parenting Scale (KIPS)

The KIPS assesses a caregiver interacting with a child during a 20-minute (maximum) video observation which is later coded against 12 key facets of parenting such as Sensitivity to Responses, Supporting Emotions and Promoting Exploration and Curiosity. It adopts a strengths-based approach promoting parental learning and building confidence.

The KIPS can be used as a baseline clinical assessment and to track progress over time and is therefore suitable for pre- and post-outcome measurement. Training to use the KIPS is available as e-learning from www.comfortconsults.com.

In 2019, prices were $155 with additional charges for the e-learning workbook, annual reaccreditation and scoring forms.

The DC: 0-5 assessment (Levels of Adaptive Functioning; LOAF)

The DC: 0-5™ assessment manual and training (sometimes referred to as the Levels of Adaptive Functioning or LOAF scale) has been devised by Zero to Three [19] as the first developmentally-based system for practitioners assessing mental health and developmental disorders in infants and toddlers. It replaces the previous Parent-Infant Relationship Global Assessment Scale (PIR-GAS) from Zero the Three. The ‘LOAF’ can be used by practitioners from various disciplines to plan treatment and evaluate progress in their parent-infant relationship work. Information about training can be accessed via the Zero to Three Learning Centre https://learningcenter.zerotothree.org/Default.aspx.

Identification of risks and stresses on the parent-infant relationship

The Gloucestershire Infant Mental Health Team has developed a checklist [20] for acknowledging the stressors and potential risks that might be negatively impacting the parent-baby relationship. Many of the PIP teams find it helpful for guiding referrers to think about potentially hidden stressors and risks in addition to the current quality of parent-infant interaction. We have provided the list in the Network Area of the ParentInfant Foundation website. See the Zero to Three website [21] for a more extensive example.

Stresses are cumulative: on the whole, more stress factors make it harder for parents to hold their child in mind and increase the possibility of maltreatment. The emotional headspace that parents need for sensitive attunement with their baby can easily be hijacked by multiple competing demands. Parents may need help to overcome these multiple challenges in order to gain a fuller understanding of their babies and then interact with them in an appropriate way.

Although it might not be possible to change the existence of many of these (such as family poverty or trauma in the parents’ childhood) it is still important to appreciate the amount of pressure that might be affecting the relationship.

Formal assessment of attachment

NICE guidance (NG26, Nov 2015) which relates to children who are adopted from care, in care or at high risk of going into care recommends that health and social care professionals should offer a child who may have attachment difficulties, and their parents/ carers, a comprehensive assessment before any intervention, which includes:

- Personal factors, including the child’s attachment pattern and relationships

- Factors associated with the child’s placement(s), such as history of placement changes, access to respite and trusted relationships within the care system

- The child’s developmental status

- Parental sensitivity

- Parental factors, including conflict between parents (such as domestic violence and abuse), parental drug and alcohol misuse or mental health problems, and parents’ and carers’ experiences of maltreatment and trauma in their own childhood

- The child’s experience of maltreatment or trauma

- The child’s physical health

- Co-existing mental health problems and neurodevelopmental conditions commonly associated with attachment difficulties, including emotional dysregulation and other signs of mental health distress, and autism.

Only two assessments tools are recommended: the Infant Strange Situation Procedure (for children aged 11-17 months) and the Attachment Q-sort (for children 12-48 months). The Infant Strange Situation is based on the work of Mary Ainsworth, Mary Main and Judith Solomon, and Pat Crittenden.

Intensive training (12 days in the UK [22] ) is offered by various private providers. Unlike the Strange Situation procedure, the Attachment Q-sort does not require a separation scenario but does require an observer to rate an infant’s behaviour after detailed observation.

The well-known Infant Care Index (www.patcrittenden.com) is a qualitative screening tool of the risk and patterns of interaction between infants 0-15 months and their carers. It is best used as part of a comprehensive risk assessment.

The procedure requires a 3-5 minute video of an infant and parent playing to be coded according to three subscales for parents and four for infants. Training to become a reliable coder takes nine days, in three-day blocks, followed by a reliability test of submitted video clips.

Training is available in the UK for professionals who work with infants and their carers. In 2019, the 9-day training costs in the region of £720 (excluding travel and accommodation) from http://www.iswmatters.co.uk/. Ongoing accreditation is required.

Choosing which interventions to offer

The ideal scenario is for a multi-disciplinary team to offer a range of evidence-informed interventions so that every family can receive a tailored package of care. The team’s therapeutic toolbox should include individual and group interventions which can cater for a range of presenting difficulties and levels of complexity. It will blend expert clinical practice with structured or manualised programmes.

Several existing teams have keyworker or similar posts which link families into other services such as housing, substance misuse or social isolation. This reduces families’ stress, facilitating their engagement in therapy and maximising its effectiveness.

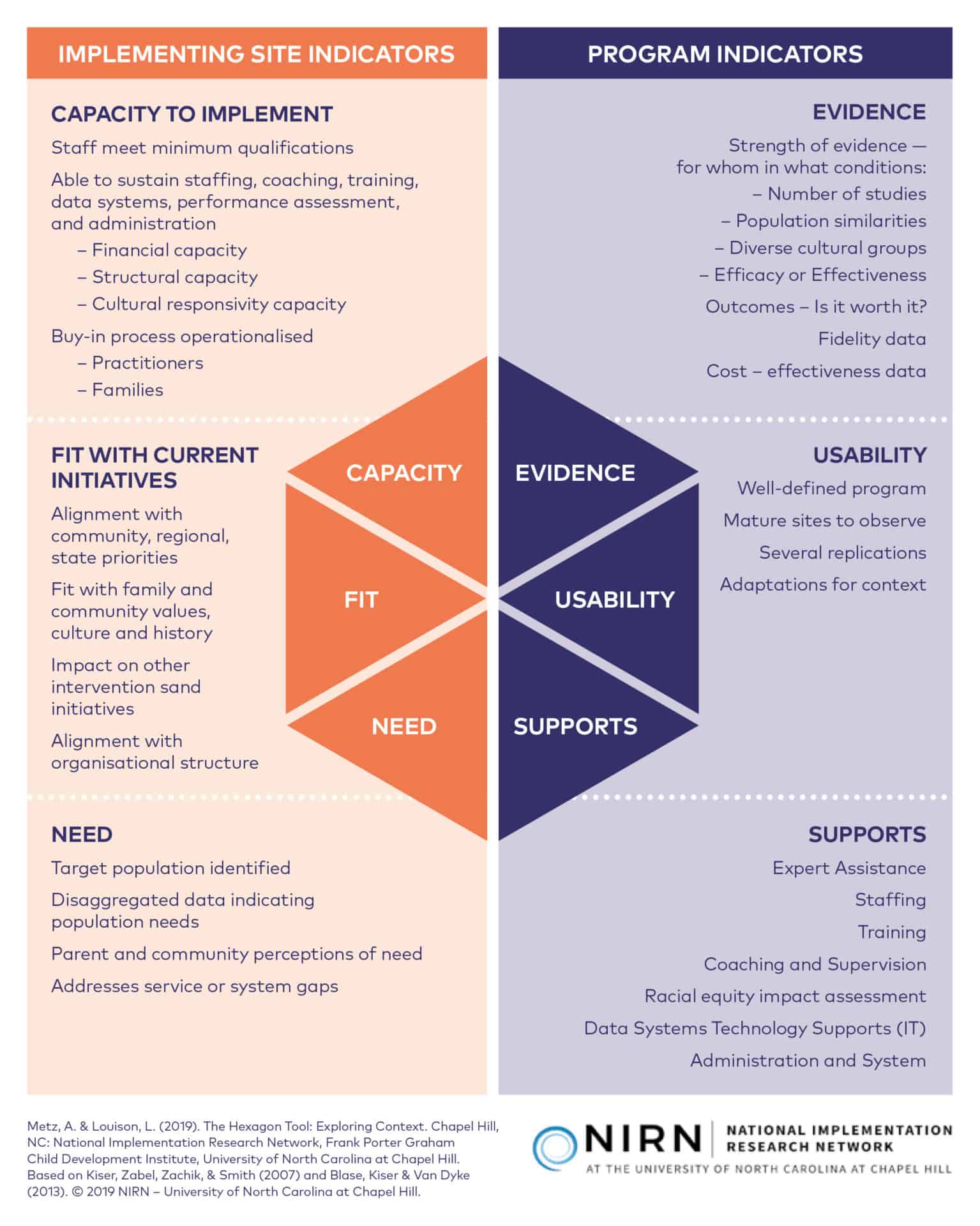

Louison and Metz (2018) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have developed the “Hexagon Tool” to help scrutinise interventions, ensure strategic fit and plan for operational requirements. It is reproduced overleaf with the permission of the authors. More information on how to use the tool can be found on the National Implementation Research Network website [23] . The Hexagon Tool can be used to develop a rigorous implementation plan to ensure chosen interventions are appropriately deployed and delivered for maximum impact.

Interventions for parents and their child together

Parent-infant teams are multi-disciplinary and work with a ‘toolbox’ approach that can be flexible in response to the family’s situation rather than being forced into the limitations of a manualised method of working. For example, individual work (parent(s) and baby seen together) and group work are not mutually exclusive and may be mutually beneficial when offered in parallel or consecutively. Below we provide information about some of the relevant, evidence-informed interventions and we will continue to add to the list as this toolkit develops.

The Hexagon: An Exploration Tool

The Hexagon can be used as a planning tool to guide selection and evaluate potential programs and practices for use.

Parent-infant psychotherapy

Parent-infant psychotherapy is historically the clinical foundation of the PIP teams and it remains the predominant therapeutic approach across those teams.

Psychotherapy is a distinctive though broad paradigm and arena of scholarship, thinking, literature and clinical practice, rooted in psychoanalysis, which gave rise to the interest and practice of infant mental health.

Parent-infant psychotherapy is a psychoanalytical and attachment-based intervention which aims to help the parent(s) reflect on past and/or present experiences which may be influencing their view of their infant and their relationship with them. The psychotherapist models sensitive responding and helps the parent to interpret their baby’s behaviour appropriately. Psychotherapy pays particular attention to the unconscious and non-verbal aspects of communication between parent(s) and their baby. Parent-infant psychotherapists are trained to work with the parent and infant (dyad), and parents and infant (triad), the couple relationship and systemically (including wider family members) as required.

Parent-infant psychotherapists complete a specific and intense professional qualification and training route which confers a depth of expertise in parent-infant relationships. They vary the exact therapeutic approach, duration, content and focus of therapy based on their professional assessment of the clinical presentation. Hence, parent-infant psychotherapy is not a singular or standardised type of intervention so it is less amenable to the kinds of evaluation typically used for a standardised or manualised intervention, such as an RCT.

The breadth of approaches within parent-infant psychotherapy raises substantial challenges for evaluation. A Cochrane review of ‘parent-infant psychotherapy’ found that it is a promising model in terms of improving attachment security in high-risk families but there is currently no evidence of its impact [24] . The review found that problems in the current evidence base were due to significant variation in the type of intervention evaluated, little consistency in the outcomes measured and low quality of evidence.

One particularly intensive form of parent-infant psychotherapy, Infant-Parent Psychotherapy (IPP), also known as the Lieberman model, has been demonstrated to improve infant attachment security in two Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs). IPP has an evidence rating of 3+ in the Early Intervention Foundation Guidebook [25] . IPP is not currently delivered in the UK, probably due to the significant resources required to deliver this level of intervention. In Infant-Parent Psychology practitioners must have 92 hours of programme training and delivery involves at least weekly hour-long sessions for around a year. However, there are similarities with the 1:1 psychotherapy offered by parent-infant psychotherapists who also undergo extensive training and can offer long term therapy.

For parents who have maltreated, or are at risk of maltreating, their pre-school child (including children under 2) NICE guidance NG26 (Pre-school children in care or at risk of going into care) recommends parent-child psychotherapy based on the Ciccetti and Toth model [26] .

Video Feedback Approaches

Video feedback approaches involve a practitioner filming the parent(s) interacting with their baby, often during everyday moments, such as play time or meal times. The parent(s) is then supported to watch and reflect on the film, using a strengths-based approach. Throughout repeated filming and review sessions, parents are helped to become more sensitive to children’s communicative attempts and to develop greater awareness of how they can respond in an attuned way.

A meta-analysis of studies using video feedback concluded that parents become more skilled in their interactions with their children and have a more positive perception of parenting which helps the overall development of their children.

In a large meta-analysis of studies which examined the effectiveness of video-feedback, Fukkink (2008) [27] found a positive, statistically significant effect on parenting behaviours. Brief video-feedback interventions with parents in high-risk groups were the most effective. The authors concluded that family programmes that include video feedback achieve a dual level effect: parents improve their interaction skills, which in turn help in the development of their children. Parents become more skilled in interacting with their young child and experience fewer problems and gain more pleasure from their role as parent.

Video feedback is also recommended in two NICE Guidelines [28] . For pre-school children (including under 2s) on the edge of care, NICE guidance NG26 provides clear guidance about the use of video feedback approaches. There are different types of video feedback interventions. The two types most commonly used in the UK are Video Interaction Guidance (VIG) and Video-Feedback Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (VIPP-SD).

In VIG, practitioners are trained to use video feedback through a series of filming and review sessions in order to encourage parents to see and build on what they are doing to help things go well and thus become aware of the positive aspects of the caregiver-infant interaction. The intervention is based on principles for attuned interactions and guidance. VIG methods, quality and standards are specified by the Association for Video Interaction Guidance UK, but the intervention allows some flexibility in delivery, meaning that it can be used by different professionals in individual or group settings to offer tailored support to parents. VIG has not yet been subject to a robust quasi-experimental or controlled evaluation in the UK although a Cochrane review is due in late 2019 [29] . The AVIG website reviews some of the research on effectiveness.

Further information, including about training, can be found at https://videointeractionguidance.net/.

VIPP-SD is a more manualised, structured approach for parents of children aged 1-6 years. It typically consists of seven two-hour sessions, working with one or both parents and one child in the home environment. It has different variants, which have been carefully tailored to work with different populations such as adopted infants, children with autism, babies of mothers with an eating disorder, fathers and couples with high levels of couple conflict. More information, including training, can be found at http://vippleiden.com/en.

The effectiveness of the original VIPP-SD programme on enhancing parental sensitive behaviour has been demonstrated through 12 RCTs in different countries and among different target groups [30] .

VIG and VIPP are not included in the Early Intervention Foundation Guidebook, but VIPP has been registered in the Effective Youth Interventions Database of the Dutch Youth Institute [31] with the highest evidence rating “demonstrably effective”.

Watch, Wait and Wonder

Watch, Wait and Wonder (WWW) is an infant-led psychotherapeutic approach developed initially by child psychiatrists Frank Johnson, Jerome Dowling, and David Wesner in Wisconsin, USA [32] . It was further developed by Elizabeth Muir and Nancy Cohen and colleagues in Toronto in the early 1990s. It can be conducted one-to-one or in groups by any suitably qualified practitioner who has attended a Watch, Wait and Wonder training and is receiving appropriate, ongoing supervision. This might be someone who works with children and families and who has some experience of therapeutic approaches.

The Watch, Wait and Wonder intervention involves 18 weekly sessions during which parents are encouraged to play with their babies in a way that follows the baby’s lead. The parent is then invited to explore the feelings and thoughts that were evoked by what he or she observed and experienced during the play. The intervention aims to enhance parental sensitivity, mentalisation and responsiveness, the child’s sense of self and self-efficacy, emotion regulation, and the parent-infant relationship.

This intervention has an evidence rating of 2+ in the Early Intervention Foundation Guidebook as there is evidence that it improves children’s attachment security, emotion regulation and cognitive development.

Watch, Wait and Wonder can also be used flexibly with fewer sessions. Dr Michael Zibilowitz, Developmental & Behavioural Paediatrician in Sydney, has developed a modified Watch, Wait and Wonder intervention which he describes as ‘a highly effective and simple way for all parents to be with their children, that has the potential to help them: enjoy their child more, stimulate their child’s creativity and imagination, help their child play more by themselves, settle difficult behaviours, and foster a surge in development’.

OXPIP offers an Introduction to Watch, Wait and Wonder (visit https://www.oxpip. org.uk/events-1/watch-wait-and-wonderan-introduction-4) and more intensive courses and supervision are available from https://watchwaitandwonder.com/

Mellow Groups

Mellow Parenting interventions are evidence-informed manualised parenting programmes. There is a family of Mellow Programmes, including Mellow Bumps for expectant parents, Mellow Mums, Mellow Dads and a group tailored for mothers with learning difficulties called Mellow Futures. These are attachment and relationship-based group interventions using a mixture of reflective and practical techniques to support parents.

They involve weekly group sessions for high-risk families. For example, a typical Mellow Mums group will run for 14 weeks, one day a week. A typical group might run between 10am and 2:30pm including a group work session, followed by a shared lunch and play with the babies.

There is a growing body of research into the Mellow programmes and two are currently undertaking an RCT. Mellow Toddlers is in the Early Intervention Foundation Guidebook, but Mellow Bumps and Mellow Babies are not. There is also a review of evidence on the What Works For Children’s Social Care? Evidence Store[33].

Information about all the training for Mellow parenting and relationship programmes is at https://www.mellowparenting.org/.

Circle of Security

Circle of Security is an attachment-based parent reflection model. It uses video to help parents to reflect on how children communicate their needs through their behaviour and to consider how best to meet these needs.

There are two forms of Circle of Security: an original 20-session programme for socially disadvantaged children from 1-5 years and a less intensive but targeted 8-10 session programme for children from four months old called Circle of Security Parenting.

Both programmes involve weekly sessions and can be used individually or in groups in a range of settings. Circle of Security Parenting has been shown through an RCT to improve children’s inhibitory control and maternal response to child distress. It has an evidence rating of 2+ in the Early Intervention Foundation Guidebook.

The four-day Circle of Security training costs approximately US$900. Details of occasional courses in the UK can be found at https://www.circleofsecurityinternational. com/find-a-training.

Attachment and Bio-behavioral Catch-up (ABC)

This manualised approach “helps caregivers nurture and respond sensitively to their infants and toddlers to foster their development and form strong healthy minds” [34] . ABC makes extensive use of video (for showing topic illustration as well as feedback) and focuses on specific parenting behaviours: nurturance, following the child’s lead and reducing frightening caregiving behaviour.

The emphasis is on a skilled reinforcement of strengths. It has been particularly effective in helping foster parents. ABC has been shown to be effective in the US with birth parents as part of an ‘edge of care’ programme and foster parents.

Research findings about child outcomes include a greater proportion of children with secure attachments and fewer with disorganised attachments compared to controls [35] , better cortisol regulation details, including links to books and references, are available at three-year follow-up [36] , less anger at 1-2 year follow-up, and higher vocabulary scores which were fully mediated by improvements in parental sensitivity [37] .

Initial training in ABC takes two days although it is not widely available outside of the US and can be costly due to the requirement for ongoing supervision. More at http://www.abcintervention.org/.

Incredible Years Parents and Babies

The Incredible Years (IY) is a comprehensive suite of parenting and classroom management groups with a well-established portfolio of evidence across its interventions. The group-based Parents and Babies programme aims to promote a positive attachment between parents and their babies aged 0-12 months [38] . Content includes becoming a new parent, developmental milestones, temperament differences, safety and building a positive parent-infant relationship. A follow-on Parent and Toddler programme is also available.

IY Parents and Babies group facilitators use video clips of simulated real-life scenarios to support learning, with group discussions, problem solving and practice skills with babies in the group.

This intervention is not yet rated by the EIF Guidebook although others from this developer are, for example, the Parent and Toddler programme has an EIF rating of 2+. Research is summarised on the Incredible Years website. A service evaluation in Wales found significant short-term increases in parental mental health and parenting confidence but did not measure parent-baby interaction [39] .

The first randomised control trial in Denmark found the programme was not effective on outcome measures related to the parent-child relationship [40] . An RCT is ongoing in the UK.

Empowering Parents Empowering Communities (EPEC): My Baby and Us

EPEC [41] is an approach developed by Centre for Parent and Child Support, South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the CAMHS Research Unit, King’s College, London.

It is an internationally recognised evidence-based peer-led parenting programme.

It provides a system for training and supervising parent-led parenting groups that help parents to learn practical parenting skills for everyday family life and develop their abilities to bring up confident, happy and cooperative children. Free crèches are provided alongside each group and parents attending the course can choose to gain accreditation for their work through the Open College Network.

The EPEC Team have received funding from NESTA and the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport to support the setting up and running of 16 new EPEC hubs in the England.

There are three core EPEC courses: one for parents of teenagers, one for parents of children aged 2-11 years and the My Baby and Us course which is for parents of babies aged up to one year. EPEC courses consist of eight 2-hour sessions, supported by on-site crèche facilities, co-facilitated by two EPEC-accredited parent group leaders for between 8-12 parents.

Courses focus on improving parent-child communication, interaction and play; parental bonding, attachment and reflective function to improve parental sensitivity and warmth; positive parenting skills to regulate and promote pro-social child behaviour and parent self-care and stress reduction.

Courses use highly interactive methods involving information sharing, group discussion, demonstration, role play and reflection. Practice and parents’ use of skills in everyday life are a key feature, with participants working on specific goals throughout their course.

EPEC has an effectiveness rating of 3 and cost rating of 1 in the EIF Guidebook.

Short-term interventions for parents with additional mental health needs

Working effectively with the parent-infant relationship means that both the parent’s and the infant’s needs are being attended to. Specialised parent-infant relationships teams often find that the parent needs some help in their own right to move past psychological barriers. This does not replace formalised adult mental health input but some focussed, short-term work on their own may help to support the parent to make progress in their parent-infant work. Similarly, some perinatal (adult) mental health therapies include thinking about the infant and the parent-infant relationship, on the basis that it cannot and should not be separated off.

Cognitive Analytical Therapy (CAT)

Cognitive Analytical Therapy is a therapeutic approach to working with adults and is used by a range of qualified professionals.

The ethos and underpinning theories align well with parent-infant work as CAT explores the events and relationships, often from childhood or earlier in life, that underpin an adult’s way of thinking and feeling. Object relations theory features in the genesis of both CAT and parent-infant psychotherapy.

“Sometimes parent-infant interventions uncover issues from the parent’s own childhoods which need addressing for the infant work to continue. A short course of CAT for a parent can unstick psychological barriers which have been impeding progress in the parent-infant work.

CAT is a really helpful model to use in this area of work because its basis is in the importance of relationships. If we always had to refer on to Adult Mental Health colleagues, the infant work might need to pause and that would mean we might lose some families.”

Sue Ranger, Consultant Clinical Psychologist and Manager of Leeds Infant Mental Health Service

CAT is a time-limited therapy (usually 16 weeks) although there is some flexibility.

CAT Training courses of differing lengths and levels, from introductory to supervisory, are available from multiple providers including the Association for Cognitive Analytical Therapy (ACAT) www.acat.me.uk. The website also has further information about CAT with FAQs for commissioners and practitioners.

Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR can be particularly helpful for addressing parental trauma which is impeding progress in the parent-infant work, including trauma resulting from the birth, previous sexual assault/abuse or other traumatic incidents.

A range of professionals can train to become an accredited EMDR therapist, with multiple levels of training on offer. The EMDR Association of UK and Ireland is a good starting point https://emdrassociation.org.uk/.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT)

CBT is a talking therapy which addresses the links between thoughts, feelings and behaviours. Typically, CBT focusses on the present rather than the past and looks for practical ways to improve a person’s state of mind in manageable steps. It might be used as an adjunct to parent-infant work where the parent is experiencing mental health difficulties or thought patterns which are interfering with the progress of parent-infant therapy.

Like CAT, some professionals will already have a basic training in CBT and multiple providers offer training of various levels across the UK. The British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies has a useful website.

Related early years interventions

Other relationship-focussed approaches employed by specialised parent-infant relationships teams or relevant to the wider workforce might include:

Peep

The Peep Learning Together Programme is based on good evidence that simple things which families can do (by providing warm, responsive relationships, a rich language environment with conversation, stories, songs, rhymes and books, and lots of play) make a difference to children’s outcomes and help children from poor backgrounds do well in education and later life.

The Programme covers five strands of development (Personal, Social and Emotional; Communication and Language; Early Literacy; Early Maths; Health and Physical Development) and can be used with babies from birth.

It is delivered to parents and children together in Peep groups, home visits and in drop-in settings. The Learning Together Programme also includes opportunities for parents to gain accredited units based on meaningful learning in context of family life which can provide a first step into further learning, volunteering or employment. Practitioners can undertake a two-day training course in order to deliver this programme.

Learning Together has a sister programme The Peep Antenatal Programme: Getting to Know Your Baby which aims to support parents (mums and dads) to:

- Think about their baby, tune in to their baby’s feelings and respond sensitively (also known as reflective function)

- Understand the importance of sensitive parenting to developing a loving, consistent and secure attachment

- Become more aware of the social and emotional aspects of the transition to parenthood

- Manage their own (sometimes difficult) feelings that are aroused by a new baby

- Meet other expectant or new parents and develop a supportive network group

- Reduce the risk to the early parent–infant relationship (by helping to prevent, for example, isolation, anxiety and low-level depression)

- Engage with other local services

The Peep Antenatal Programme can be used during pregnancy (from 28+ weeks is recommended) to the early weeks following birth. It can be used in a range of contexts and settings including one-to-one work with parent and baby, in the home or in other settings, and small group work. Practitioners can undertake one-day antenatal training which includes skills, knowledge and comprehensive resources.

The Learning Together Programme evidence includes the Birth to School Study, a longitudinal evaluation Programme, with a sample of 600 families.

The study was carried out by the University of Oxford (2005) and found outcomes for parents on the quality of the care-giving environment, and for children in skills related to future literacy success: vocabulary; phonological awareness of rhyme and alliteration; letter identification; understanding of books and print and writing. Peep children had significantly higher self-esteem. A Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) of the programme is currently being carried out by Queen’s University Belfast. It is one of the largest studies to be carried out on a parenting programme and findings will be published in late 2019.

Further details about the Learning Together Programme, Peep Antenatal Training and other programmes can be found www.peeple.org.uk.

Watch Me Play

Watch Me Play [42] was developed in Haringey First Step, part of the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust. It is an intervention to promote child-led play in order to enhance relationships and inform child-centred care planning. The programme manuals are freely available on the Watch Me Play website.

Increasing capacity in the local system

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams have an important role in increasing the capacity of the local system to support families during the first 1001 days. This can be achieved through workforce training at all levels, consultation and outreach or joint working with relevant parts of the system. In our experience, these activities only succeed where good relationships are built upon credibility, trust and mutual understanding between services.

Asking for help and advice from another, such as through consultation or joint working, is a step of faith which needs to be received respectfully and this is true for both families and practitioners.

Workforce training

Most specialised parent-infant training teams offer some form of training about the emotional wellbeing of babies and the parent-infant relationship. Some have developed a training offer tailored to their local context. For example, Leeds Infant Mental Health Service [43] has trained over 2500 local practitioners in their Babies’ Brains and Bonding course. This training integrates neuroscientific research about how babies develop with attachment theory and evidence-based practice on how to support emotional and social development in the early years of life. Importantly, this training is also offered free to the third sector.

OXPIP [44] offers a wide range of courses including extended courses on infant observation and a parent-infant therapist diploma, short courses such as ghosts in the nursery, emotional regulation and group work, and public lectures.

ABCPiP in Northern Ireland have found Five to Thrive to be a popular and useful element of their workforce training offer. It has also helped them create engaging resources for parents. Five to Thrive is a suite of resources, tools and training content built around five building blocks for a healthy brain: respond, cuddle, relax, play, talk. These themes are drawn from research into the key processes of attachment and attunement that forge bonds between young children and their carers. Practitioner training is either face-to-face or online via https://fivetothrive.org.uk/.

In Newcastle, NEWPIP offer an Infant Mental Health Course that is an intensive multi-agency 10-week course for professionals working to promote infant mental health and development. It helps professionals address difficulties in the parent-infant relationship and to enhance their skills in early intervention.

The course is a practical and theoretical introduction to some essential themes concerning the foundations of emotional, cognitive and personality development in babies and young children in the context of their primary relationships and experiences.

It considers infant development from the perspectives of psychoanalysis, attachment theory, infant developmental research and social policy.

There is a focus on the development of participants’ observation skills to make the connection between feelings, needs and behaviour. Weekly seminars explore pioneering studies and clinical approaches and involve in-depth discussion of participants’ own case work and clinical experiences.

The course is three hours per week with a requirement to read and prepare for seminars and to carry out a one-hour infant observation outside of the course hours. The course is accredited with 35 CPD hours through the CPD Standards Office. There is also a ‘Train the Trainer’ franchise model for areas outside of Newcastle. The fee includes initial tutor fees, the licence to deliver the course and participants’ course packs.

Please contact [email protected] for further details.

The Greater Manchester Perinatal Infant Mental Health Training Matrix (Feb 2019) is a comprehensive description of their local workforce training approach, and is free to download from the Network area of the Parent-Infant Foundation website.

We advise you to offer training to all levels of leadership, management and frontline practice so that awareness is raised and a shared language is adopted across the system. In time, we hope all relevant courses will map their training content against the Association of Infant Mental Health UK (AIMH-UK) competencies framework [45] .

Below, we describe some national training courses which have been subjected to independent evaluation.

Solihull Approach

The Solihull Approach is an evidence-based approach to improving emotional health and wellbeing through relationships starting from the antenatal period through childhood into adulthood. It integrates psychodynamic ideas of containment and parallel process with reciprocity and managing behaviour and is therefore highly relevant to practitioners working with the parent-infant relationship.

The Solihull Approach was developed in the mid-1990s by a multi-disciplinary team of NHS child psychotherapists, psychologists, health visitors and school nurses. It now offers a suite of relationship-based practitioner trainings which can be used across the lifespan, in universal and targeted settings, in frontline practice and management relationships.

Use of the Solihull Approach is widespread across the UK, often delivered initially as workforce training for individual practice but then developed into groups for parents at various stages of their journey through parenthood. Its focus on the quality of interaction between child and parent(s) raises frontline practitioners’ confidence in supporting families with infants [46] and provides a good basis for consultations between specialised teams and universal services.

The training offer includes: two-day foundation training for antenatal teams, perinatal teams and early years teams; training for facilitators to deliver the antenatal group, postnatal group, postnatal plus group and parenting group (1-19 years); training for facilitators to deliver the peer breastfeeding supporter training; three online courses for parents: antenatal, postnatal and ‘Understanding your child’ 1-19 years (this course also available in Urdu, Arabic, Bulgarian, Chinese and Polish); advanced training days and online training on ‘Understanding trauma’, ‘Understanding attachment’ and ‘Understanding brain development’.

‘Understanding Your Child’, the Solihull Approach manualised parenting group for 0-18 years, is reviewed in the EIF Guidebook with an evidence rating of 2 and a cost rating of 1. Other published evidence appears at www.solihullapproachparenting.com.

The Family Partnership Model and the Antenatal/Postnatal Promotional Guides System

The Family Partnership Model (previously known as the Parent Advisor Model) is an evidence-based approach to working with children and families that demonstrates how specific helper qualities and skills, when used in partnership, enable parents and families to overcome their difficulties, build strengths and resilience and fulfil their goals more effectively [47] .

It is used in practice for prevention and early intervention with childhood and family difficulties and in the management of complex longer-term psychosocial difficulties. The model has been widely adopted by community health and early help services, where it has been used to improve prevention and early intervention for families experiencing a range of health and psychosocial needs during pregnancy, infancy and early childhood.

A review of research [48] showed some positive impacts including improving parent-child interaction.

The Antenatal/Postnatal Promotional Guide System is an additional component of the Family Partnership Model that has been developed specifically for health visitors to facilitate screening and support to families during pregnancy and infancy. It can be used to assess and enhance parent-infant relationships, parental bonding, reflective function and sensitivity, family transition and support risk analysis and decision-making. The guides enable sensitive and attuned exploration of key areas of early development and parenting including foetal and infant growth, health and wellbeing of mother, father/partner and baby; couple relationship; parent-infant care, nurture and interaction; developmental tasks of early parenthood and infancy. Barlow and Coe (2013) found that the Antenatal/Postnatal Promotional Guide System provides a significant opportunity to identify and strengthen aspects of parental functioning and parent-infant interaction. The Centre for Parent and Child Support provides a range of training packages including in the programmes described above, as well as through a licensed cascade system of trained trainers. More information is available at www.cpcs.org.uk.

Consultation, outreach and joint working

The Parent-Infant Foundation defines consultation as a conversation between a parent-infant team practitioner (consultant) and another worker outside of that team (consultee) for the purpose of discussing the consultee’s work with families and providing access to the consultant’s expertise in parent-infant relationships. This might be on a one-to-one basis or in small groups. For example, BrightPiP offers regular health visitor reflective practice meetings which are open to all health visitors who want to participate in case discussion with a parent-infant therapist in a safe and supportive environment.

Understanding good practice in consultation about what should be recorded, where notes should be kept and how accountability and risk are managed is dealt with in Chapter 6 From Set-up to Sustainability. Consultation, like supervision, is a welcome activity with many benefits for families and workers because it:

- Allows practitioners to seek the expert advice of others without families needing a formal referral (thereby preventing unnecessary referrals) or whilst families are on a waiting list for specialised services

- Can be an excellent form of professional learning

- Can provide an additional quality assurance function

- Raises awareness of the parent-infant team and the benefits of the work they offer

- Improves inter-professional communication and mutual understanding of roles

- Encourages a shared language and understanding of babies’ emotional wellbeing across the system

Outreach and joint working can build further professional awareness of babies’ emotional wellbeing and offer families specialised parent-infant relationship interventions as part of their wider care. For example, the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families runs therapeutic weighing clinics [49] , a parent-toddler group at a 136-bed homeless hostel for families [50] and has run specialist parent-infant group work with mothers in prisons which was demonstrated to have a positive impact in an RCT study [51] . In Bradford, where the community is very diverse and over 120 languages are spoken, the Little Minds Matter team in Bradford has trained interpreters to enable them to work more effectively with the service. At LivPIP, one of the senior therapists has built relationships at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and offers regular consultation and joint working there. In Croydon, families referred by children’s social care are frequently offered a joint visit with the allocated social worker to maximise co-ordination and understanding across agencies, and to help the family feel held through the engagement process.

Given how immensely busy practitioners are across the system, it can take quite a while, sometimes months or even years, and sustained effort, to build the credibility and trust upon which sound professional relationships are built. Existing parent-infant teams tell us that the offer of free workforce training was often an important precursor in forging new relationships with services that then led to further consultation and joint working.

Downloads

Footnotes

[1] Asmussen, K., Feinstein, L., Martin, J., & Chowdry, H. (2016). Foundations for life: What works to support parent child interaction in the early years. London: Early Intervention Foundation.

[2] The Early Intervention Guidebook website https://guidebook.eif.org.uk/

[3] https://guidebook.eif.org.uk/about-the-guidebook/other-programmes

[4] The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare: Information and Resources for Child Welfare Professionals. https://www.cebc4cw.org/search/results/?keyword=infant

[5] Guthrie K., Louie J., David T. & Foster C. (2005) The Challenge of Assessing Policy and Advocacy Activities: Strategies for a Prospective Evaluation Approach. The California Endowment: Los Angeles.

[6] How to Build a Theory of Change https://knowhow.ncvo.org.uk/how-to/how-to-build-a-theory-of-change

[7] Asmussen, K., Brims, L. & McBride, T. (2019). 10 Steps for Evaluation Success. The Early Intervention Foundation, London. https://www.eif.org.uk/resource/10-steps-for-evaluation-success

[8] Elizabeth Stokoe (2018) Talk: The Science of Conversation. London: Robinson

[9] Ingoldsby, E.M. Review of Interventions to Improve Family Engagement and Retention in Parent and Child Mental Health Programs. J Child Fam Stud (2010) 19:629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9350-2

[10] The Health Foundation (2011). Training professionals in motivational interviewing. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/training-professionals-in-motivational-interviewing

[11] Bateson, K., Darwin, Z., Galdas, P. and Rosan, C. (2017) Engaging fathers: Acknowledging the barriers. Journal of Health Visiting, 5 (3). pp. 126-132. ISSN 2050-8719 http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/111579/

[12] Underdown, A. and Barlow, J. (2011). Interventions to support early relationships: Mechanisms identified within infant massage programmes. January 2011. Community Practitioner: the journal of the Community Practitioners’ & Health Visitors’ Association 84(4). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263749630_Interventions_to_support_early_relationships_Mechanisms_identified_within_infant_massage_programmes

[13] International Association for Infant Massage, 2019. http://www.iaim.org.uk/about-baby-massage.htm

[14] Glover, V. (2002). Benefits of infant massage for mothers with postnatal depression. Seminars in Neonatology, 7(6), 495-500. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1084275602901545

[15] Kerstan-Alvarez, L. E., Hosman, C. M. H., Riksen-Walraven, J. M. et al. (2011). Which preventative interventions effectively enhance depressed mothers’ sensitivity? A meta-analysis. Infant Mental Health Journal, 32, (3), 362-376 (p372).

[16] Underdown, A., Norwood, R. & Barlow, J. (2013) A realist evaluation of the processes and outcomes of infant massage programs. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34, (6), 483-495.

[17] Free, F., Alechina, I., & Zahn-Waxler, C. (1996) Affective language between depressed mothers and their children: The potential impact of psychotherapy. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, (6), 783-790

[18] ABC PiP in Ballygowan, Bright PiP, Croydon Best Start PiP, DorPIP, EPIP, LivPIP, NEWPIP, NorPIP and OXPIP

[19] Zero to Three. DC:0–5™ Manual and Training https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/2221-dc-0-5-manual-and-training

[20]The Wave Trust (2013). Conception to 2: Age of Opportunity. Appendix 2C p.89. https://www.wavetrust.org/conception-to-age-2-the-age-of-opportunity

[21] Zero to Three. The Psychosocial and environmental stressors checklist. https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/preview/425bc4ce-5d05-49b5-9893-b279bf155243

[22] https://iswmatters.co.uk/training/the-infant-strange-situation/

[23] National Implementation Research Network (2018). The Hexagon: an exploration tool. https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/resources/hexagon-exploration-tool

[24] Barlow, J., Bennett, C., Midgley, N., Larkin, S. K., & Wei, Y. (2015). Parent‐infant psychotherapy for improving parental and infant mental health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1).

[25] The Early Intervention Guidebook website https://guidebook.eif.org.uk/

[26] Cicchetti, D., Toth, S. and Rogosh, F. (1999). Attachment & Human Development Vol. 1 No. 1 April 1999 34-66 The efficacy of toddler-parent psychotherapy to increase attachment security in off- spring of depressed mothers http://childparentpsychotherapy.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/cicchetti-toth-rogosh-1999-efficacy-of-tpp-depressedmoms-j-h-dev.pdf

[27] Fukkink, R.G. (2008). Video feedback in widescreen: A meta-analysis of family programs. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 904-16. from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/429740/150520RapidReviewHealthyChildProg_UPDATE_poisons_final.pdf

[28] NICE guideline (NG26, 2016) Children’s attachment: attachment in children and young people who are adopted from care, in care or at high risk of going into care. Public health guideline (PH40, 2012) Social and emotional wellbeing: early years.

[29] O’Hara, L., Smith, E.R., Barlow, J., Livingstone, N., Herath, N.I.N.S., We,i Y., Spreckelsen T.F., Macdonald, G. (forthcoming). Video feedback for parental sensitivity and attachment security in children under five years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cochrane Library.

[30] VIPP-SD website http://vippleiden.com/en/professionals/scientific-research

[31] Nederlands Jeugd Instituut https://www.nji.nl/nl/Video-feedback-Intervention-to-Promote-Positive-Parenting-and-Sensitive-Discipline-(VIPP-SD)

[32] Johnson, F.K., Dowling, J., & Wesner, D. (1980). Notes on infant psychotherapy. Infant Mental Health Journal, 1, 19–33

[33] What Works for Children’s Social Care website. Mellow Parenting. https://whatworks-csc.org.uk/evidence/evidence-store/intervention/mellow-parenting/

[34] Attachment and Biobehavioural Catchup website abcintervention.org

[35] Bernard, K., Dozier, M., Bick, J., Lewis-Morrarty, E., Lindhiem, O., & Carlson, E. (2012). Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: results of a randomized clinical trial. Child development, 83(2), 623–636. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3305815/

[36] Bernard, K., Hostinar, C. and Dozier, M. (2015) Intervention Effects on Diurnal Cortisol Rhythms of CPS-Referred Infants Persist into Early Childhood: Preschool Follow-up Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015 February ; 169(2): 112–119. doi:10.1001/ jamapediatrics.2014.2369. http://www.abcintervention.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2015-Bernard-Hostinar-Dozier.pdf

[37] Lind, T., Bernard, K., Ross, E. and Dozier M. (2014). Intervention effects on negative affect of CPS-referred children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 1459–1467. http://www.abcintervention.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2014-Lind-et-al.pdf

[38] White, C. and Webster-Stratton, C. (2014) The Incredible Years Baby and Toddler Programmes: Promoting attachment and infants’ brain development. Parent Education Programme. http://www.incredibleyears.com/wp-content/uploads/Incredible-Years-baby-toddler-programmes-promoting-attachment-2014.pdf

[39] Evans, S., Davies, S., Williams, M. and Hutchings, J. (2015). Short-term benefits from the incredible years parents and babies programme in Powys. Community Practitioner, vol. 88, no. 9, 2015, p. 46+. Gale Academic Onefile. https://go.galegroup.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA436440017&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=14622815&p=AONE&sw=w.

[40] Pontoppidan M, Klest SK, SandoyTM (2016) The Incredible Years Parents and Babies Program: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 11(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167592 https://pure.vive.dk/ws/files/670324/file.pdf

[41] Centre for Parent and Child Support website. http://www.cpcs.org.uk/index.php?page=empowering-parents-empowering-communities

[42] Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust website. Watch me play: supporting babies and young children in care. https://tavistockandportman.nhs.uk/care-and-treatment/our-clinical-services/first-step/watch-me-play-supporting-babies-andyoung-children-care/

[43] Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust website. Infant Mental Health. https://www.leedscommunityhealthcare.nhs.uk/our-services-a-z/infant-mental-health/

[44] OXPIP website https://www.oxpip.org.uk/training

[45] The Association of Infant Mental Health (UK) website. The Infant Mental Health Competencies Framework (Pregnancy-2 years). https://aimh.org.uk/infant-mental-health-competencies-framework/

[46] Douglas, H. and Ginty, M. (2001) The Solihull Approach: changes in health visiting practice. Community Practitioner 2001, 74 (6): 222-224. http://s571809705.websitehome.co.uk/Images2/changes-in-health-visiting-practice.pdf

[47] Day, C. and Harris, L. (2013) The Family Partnership Model: Evidence-based effective partnerships. Journal of Health Visiting, Vol 1(1). https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/10.12968/johv.2013.1.1.54

[48] Schrader-McMillan, A., Barnes, J. and Barlow, J. (2012). Primary study evidence on effectiveness of interventions (home, early education, child care) in promoting social and emotional wellbeing of vulnerable children under 5. Page 4 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph40/documents/social-and-emotional-wellbeing-early-years-expert-report-12

[49] Sleed, M., James, J., Baradon, T., Newbery, J., & Fonagy, P. (2013). A psychotherapeutic baby clinic in a hostel for homeless families: Practice and evaluation. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 86(1), 1-18.

[50] Zaphiriou Woods, M., & Pretorius, I. M. (2016). Observing, playing and supporting development: Anna Freud’s toddler groups past and present. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 42(2), 135-151.

[51] Sleed, M., Baradon, T., & Fonagy, P. (2013). New Beginnings for mothers and babies in prison: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Attachment & Human Development, 15(4), 349-367.

This chapter is subject to the legal disclaimers as outlined here.

This chapter is correct at the time of publication, 1st October 2019, and is due for review on 1st January 2021.