Chapter contents

Chapter summary

Chapter 5 dealt with how to prepare for operational delivery. Chapter 6 will help you on your development journey from opening the doors to families to becoming a sustainable service. The information is sourced from the collective expertise of many practitioners, clinical and operational leads and implementation specialists across the field of parent-infant relationships, including many of the existing teams.

Topics covered include how to manage referrals and waiting lists, initial contact and engagement, screening and assessment, managing beginnings and endings with families, and follow-up. It is not intended as a guide in how to be a parent-infant practitioner, but as a collection of learning and prompts to guide you in how you organise the work with families.

You can download this chapter as a PDF here, or simply scroll down to read on screen.

Finding families to work with

Reaching the families who will benefit most from working with a specialised parent-infant relationship team can be initiated in several ways:

- Accepting families through consultation activity with other services. Some new parent-infant teams start out initially not by accepting referrals but by offering consultation and joint visits with colleagues in other services. This helps manage the inflow of families and creates a mutual exchange of learning between organisations

- Accepting families directly from practitioners e.g. midwives, GPs, health visitors, social workers, children’s centres, etc.

- Accepting self-referrals*. Many teams worry that self-referrals will inundate them, but self-referrals can be a helpful mechanism to stimulate numbers of referrals, for example in smaller charities who are just setting up, or where the team wants to break down accessibility barriers (such as having to get a professional referral)

As described in Chapter 5, building relationships with referrers* is key. Meaningful dialogue about their contexts and ways of working helps referral pathways to be designed to be easy to use. Workforce training from specialised teams supports referrers to make appropriate and timely referrals and to help them have conversations with families which de-stigmatise referral.

* “referrals” and “referrers” is language typically used in health settings. Teams may prefer to use the alternative language of “registrations”.

Start by screening for suitability

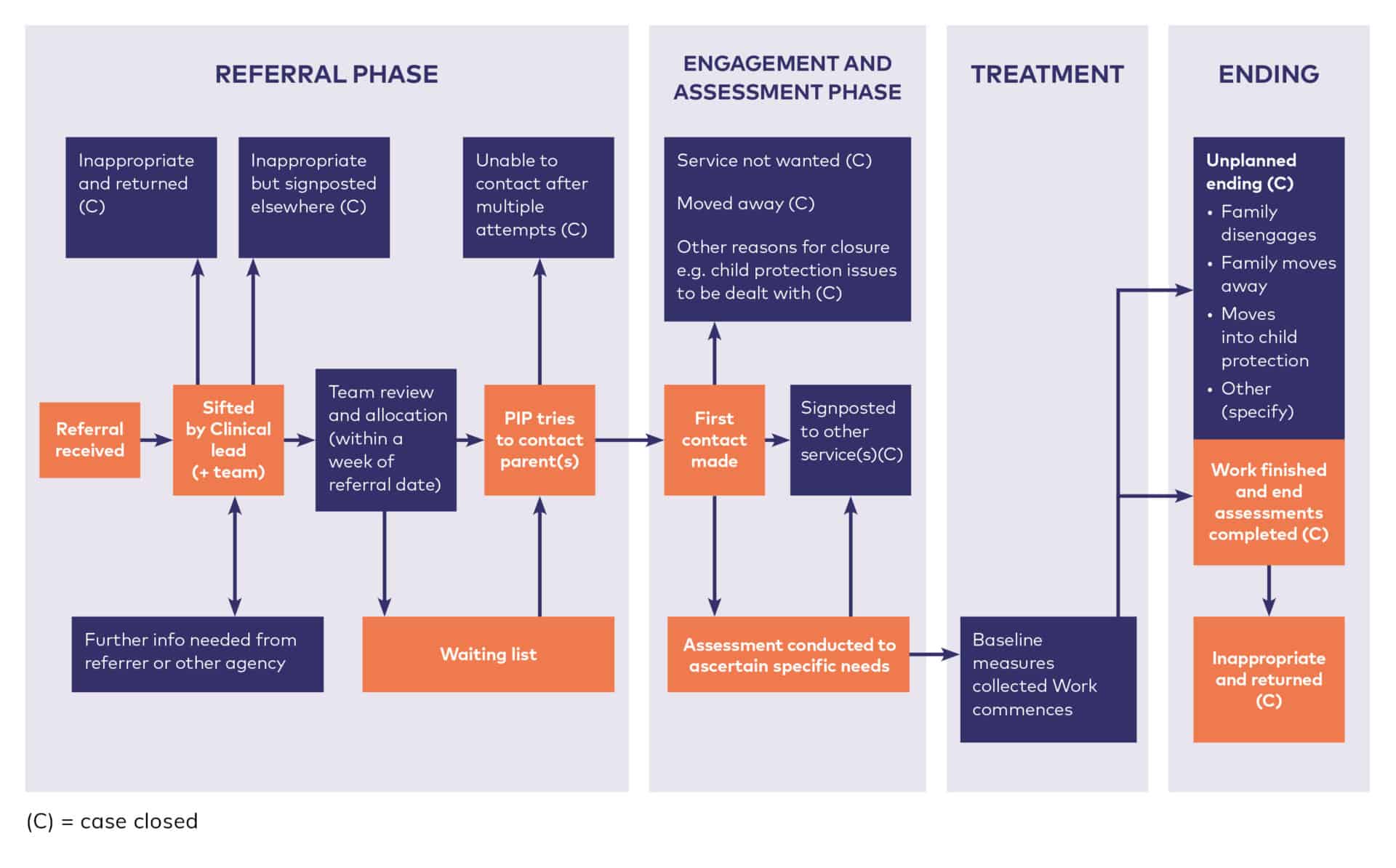

Not all referrals will be suitable for the team: some will not meet the eligibility/referral criteria, some will not have enough information for you to make a decision, some referrals will be unclear about whether the family is aware of and has agreed to the referral in the first place.

Parent-infant teams tend to be more likely to accept referrals that clearly identify recognised risk factors or current stressors that may be putting the caregiving relationship at risk. The team can then complete an observational and interview-based assessment to establish the extent, intensity and urgency of the difficulties in the parent-infant relationship.

There are different ways to prioritise referrals:

- Chronologically. Some teams see families in the order they have been referred

- By risks and stressors. Some teams prioritise those parent-infant relationships exhibiting many/certain types of risks and stressors

- Triage. Some teams triage all families equally quickly and then prioritise from there

PIP teams such as Croydon Best Start PIP have been using the list of risk factors [1] developed by Gloucestershire Infant Mental Health team to support referrers and their own practitioners when thinking about the stresses and risks individual parent-infant relationships are under.

Those considered to be the most significant risk factors are underlined. One significant risk factor is considered sufficient reason for referral, but as risks are cumulative, four or more ‘minor’ risks also qualify for referral.

Typically, the team’s Clinical Lead sifts through new referrals for ones that are obviously unsuitable and then explains the reasons to the referrer and suggests an alternative service for the family, if appropriate. In some instances, the whole team reviews referrals together. Ideally, this is done within a working week of receiving the referral but you may need to gather more information on the situation in the family and their context before being able to make a decision.

Once the team accepts a referral, the family are placed on the waiting list or allocated to a practitioner within the team and the family is informed with copy to the referrer. If you accept self-referrals, you should inform the Health Visitor and GP of the referral and outcome (according to your consent to share information policy).

‘Studies show that early intervention works best when it is made available to children experiencing particular risks’ [2]

Managing a waiting list

If you reach the point where you need to manage a waiting list, you should work cooperatively with all the referring agencies to make sure that being on the waiting list does not lead the referrer or other services to withdraw or lower their level of support for that family.

If referring services withdraw ongoing support, the family may feel abandoned or resentful of the referral, reducing the likelihood of them engaging with the new service and potentially raising a safeguarding risk.

Typical referral management process

Allocation within the team

Typically, teams discuss appropriate referrals at a weekly team meeting. Families are allocated to the practitioner with the professional skills most suited to the families’ needs although some teams might operate on a locality or assessment clinic basis. The assigned practitioner will make any final enquiries to the referrer and make the first contact with the family. This can take time and persistence if families are unsure about engaging or their contact is erratic.

Some teams have keyworker roles to help both with this first engagement and with later aspects of supporting the family. Some parent-infant teams put a time limit on how long to attempt engagement before the family are referred back to the original referrer. Trust might be difficult for families experiencing relationship problems so sensitive, well-timed and respectful approaches are crucial.

Trauma Informed Approaches

Many parents referred to a specialised parent-infant relationship team will have experienced at least one, if not multiple, forms of trauma during their lifetimes. This may not be detailed in the referral and may not be obvious at first contact but may be impacting on the parent-infant relationship and making it hard for parents to engage. Being trauma-informed means approaching everyone in a respectful, transparent and empowering way such that contact is not re-traumatising and does create the conditions of safety needed for that person to trust and engage.

Some of the elements of trauma-informed practice are described in this Research in Practice Blog [3] , this Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Infographic [4] and in this review article by Sweeney et al (2016). [5]

Making first contact

First contact is the moment when the allocated practitioner contacts the family to say hello, welcome them to the service and arrange the first appointment, and there are various ways to do this.

- Text: we have heard from parents across the network that texting is a popular way to make the first contact as it is less personal than a phone call but more personal than a letter. Many service users find this a comfortable first contact and a helpful way to be reminded of appointments. Teams need a policy in place for contact by text, to include how to respond to information shared out of hours and how to manage risk.

- Contact with both parents: where a couple have been referred with their baby, the first contact should be to both parents.

- Tailored to needs: sensitive approaches to literacy and learning difficulties may favour text or phone as the first contact, but with a follow-up letter to confirm the date and time of any appointments.

- Additional information: some parent-infant teams include leaflets or baseline assessment questionnaires in the letter confirming the first appointment, as well as any outstanding consent forms, although others prefer to wait until they’ve met the family.

The first appointment

Though there may be times when a phone consultation is offered first, most specialised parent-infant relationship teams offer a face-to-face appointment. Unless there is an issue of safety, the first appointment might be a home visit.

It is worth considering, with the parents’ permission, inviting the referrer to the first appointment. This improves the families’ experience of transition, improves communication between professionals and with the family, and can offer mutual learning between parent-infant teams and referrers.

When it comes to scheduling appointments, families with older children can find it hard to attend during periods of the day which clash with school drop-off and pick-up times. We have heard from teams that sending text reminders a day or two before the appointment can increase attendance rates.

Agreeing further work

At the end of the first appointment, the practitioner will typically check that the family fully understands that their relationship with their baby is the focus of the work and discusses an offer of further work.

This is likely to involve further assessment in the first instance, with a view to finding the most appropriate intervention approach to follow. Information management systems may need to be able to accommodate these different types of sessions.

Letters

You may wish to consider addressing any follow-up letters to the parents who attended and copy these to other professionals and absent parents, rather than write to professionals with copies to parents.

Interventions

Assessments and interventions are described in Chapter 4 Clinical Interventions and Evidence Informed Practice

Managing endings

Whilst this toolkit is not a clinical guide, we do often get asked about clinical endings by operational leads. Sustainable teams need families to flow into and out of the service, otherwise the backlog can lead to lengthy waiting lists and practitioners feeling swamped.

Some specialised parent-infant relationship teams limit sessions in parts of their service, typically to 5 or 6 sessions, but allow flexibility for those families who clearly need additional work to get the parent-infant relationship back on track. Certain interventions offer a fixed number of sessions.

How relationships begin and end is significant, and ending a therapeutic relationship is typically an extended phase rather than one ending session. The ending should be negotiated with the family at an appropriate time in advance, leaving enough sessions to work this through. A review session mid-way through the work can establish what more work the parent thinks remains to be done. It is not uncommon for families to discover another issue they want support with when the work starts coming to a close.

Some families appreciate transition to step down services such as Infant Massage or universal parenting groups such as Solihull Approach, or into community-based services which can support their social connectedness. DorPIP runs Keep In Touch group sessions once families have completed therapy.

There is a helpful report [6] on the Anna Freud Centre website about ending treatment in challenging circumstances.

Follow up

There may be advantages to practitioners following up families after six months or so, for example if they are keen to collect followup outcome measures or monitor the success of intervention. Many teams do not have the capacity to do this. It is worth remembering that some clinical recording systems would require the case-notes to be re-opened if there was a successful follow-up.

Sharing information with others

At any point in the work with families, information may come to light that the practitioner believes could be beneficially shared with another. All parent-infant relationship teams are required to follow data protection legislation and the guidance set out in Government guidance. [7] This states: ‘Information sharing is essential for effective safeguarding and promoting the welfare of children and young people. It is a key factor identified in many serious case reviews (SCRs), where poor information sharing has resulted in missed opportunities to take action that keeps children and young people safe.’

Information sharing is also good practice when there are no safeguarding issues. However, since a parent-infant relationship team is providing a therapeutic service, patient confidentiality applies and (unless there is an immediate observed safeguarding concern) no personal information derived from the work should ever be shared without formal permission. The ethical guidelines from professional associations should be followed at all times, as should the guidance set out in the NHS England Confidentiality Policy. [8]

‘All employees working in the NHS are bound by a legal duty of confidence to protect personal information they may come into contact with during the course of their work. This is not just a requirement of their contractual responsibilities but also a requirement within the common law duty of confidence and the Data Protection Act 2018. It is also a requirement within the NHS Care Record Guarantee, produced to assure patients regarding the use of their information.’

Recording clinical notes

All public sector organisations and registered professionals will have their own record keeping policies and guidance from professional bodies. Details of professional bodies can be found in Chapter 6 Recruitment, Management and Supervision.

For anyone who needs to develop their own, there is a Clinical Record Keeping policy template in the resources section and you are advised to have your policy ratified by your Executive Team or Board of Trustees. You may need to reference record keeping procedures in your home worker and lone worker policies.

The Parent-Infant Foundation can support you in developing record keeping policies and procedures, please contact us through our website.

Whether notes are kept in the parents or child’s name is often determined by where the team is located in the system. Parent-infant teams that are managed within CAMHS, health visiting or children’s social care keep records in the child’s name. This has the benefit of the records staying with the child if their carers change e.g. if the child goes into care. The child can access the notes when s/he is older, as can every adult with parental responsibility (which may be problematic if the parents are separated), although information about any adult may need to be redacted, including all references to either parent such as details of their past or present experiences.

The Leeds Infant Mental Health Service is managed through CAMHS so the record management system has been adapted to accommodate antenatal referrals. The child is referred to as ‘Baby of [Mother’s name]’ with the Expected Due Date as date of birth, which is then updated once the baby is born.

If the parent-infant team is managed through perinatal (adult) mental health or a charity, the records are typically kept in one of the parent’s names. This prevents the child, and an abusive or separated other parent, from accessing the notes. It can also make it easier to link safeguarding information where one parent may have several children with different surnames.

The Parent-Infant Foundation advocates for the meaningful engagement of male parents and carers in all work, where this is safe for the mother and child. We ask that all teams gather, share and record information in a way that supports a father’s and / or partner’s important role in the infant’s life. This includes recording their contact details, understanding their relationship with the baby and actively bringing them into the work as much as possible where clinically appropriate.

Accountability, risk management and note-keeping in consultation

The Parent-Infant Foundation defines consultation as a conversation between a parent-infant team practitioner (consultant) and another worker outside of that team (consultee) for the purpose of discussing the consultees’ work with families and providing access to the consultant’s expertise in parent-infant relationships.

Understanding good practice in consultation, including what should be recorded, where notes should be kept, how accountability and risk are managed, can be a grey area. Consultation, like supervision, is a welcome activity with many benefits for families and workers because it:

- Allows practitioners to seek the expert advice of others without families needing a formal referral, thereby preventing unnecessary referrals

- Can be an excellent form of professional learning

- Can provide a useful quality assurance function

- Gets the right advice to those already working with the family without the need for a waiting list or face to face appointment

- Raises awareness of the parent-infant team and the benefits of the work they offer

- Improves inter-professional communication and mutual understanding of roles

- Encourages a shared language and understanding of babies’ emotional wellbeing across the system

We advise all specialised parent-infant teams to follow the consultation policy of their host organisation, and to provide a clear statement about consultation note-keeping, and issues of accountability and risk management to all consultees. In the absence of a specific local policy on consultation there may be an organisational policy on supervision and notekeeping which can be used to inform practice. Teams should consider the following questions if writing their own consultation policies.

Note-keeping

Should there be one shared record of the consultation which both the consultant and consultee keep, or should each record the consultation separately?

Most consultations occur anonymously, without the families’ knowledge, because like supervision it is provided as a support mechanism to the person already working with the family. As such, the anonymised notes are likely treated the same as supervision notes. If consultation occurs with the family’s consent, might notes of the consultation be kept in the families’ notes? And, how should the consultation time be recorded in the consultees diary system (as a clinical contact against the families’ name or as generic consultation time)?

Who has access to consultation notes? For example, does the consultees’ manager have access to consultation notes in the event of a concern or later enquiry?

Accountability and risk management

Whilst consultation is very similar to supervision, it usually crosses organisational boundaries so the accountability arrangements are likely to differ. Is there a need for a written agreement between consultants and consultees stating that advice given during consultation is based on information provided by the consultee, and that the consultee and his/her employer remain accountable for the consultee’s decisions and actions?

There are rare occasions when the consultant has significant concerns during consultation, for example about safeguarding issues or the capability of the consultee. How will consultants respond and manage their concerns?

Team meetings and case discussion

Specialised parent-infant relationship teams around the UK tend to have two types of team meeting as a minimum: a team business meeting where non-clinical matters such as future developments, capacity challenges, building maintenance, mandatory training and other operational necessities are discussed and then a clinically-focussed meeting which may encompass referral allocation, caseload reviews and case discussions. These might be supplemented by formal peer or external supervision meetings, journal or book clubs, and topic- or profession-specific supervision groups (e.g. safeguarding supervision).

Caseload management

Caseloads should be determined locally but as a rule of thumb, for individual work four families are seen in a normal 7.5 hour working day. This figure is based on the assumptions that the case load will be mixed (including some very complex families requiring liaison with multiple external and internal colleagues and potentially multiple modalities of therapy, alongside more straightforward work) and that the practitioner will be given dedicated time for team meetings, training etc.

A two-hour group session is likely to require at least one hour’s preparation and one hour’s follow-up for experienced group facilitators and considerably more for practitioners new to that intervention.

Recording non-clinical work

We advise all specialised parent-infant relationship teams to record their non-clinical activity, such as consultation, delivery of training, strategy development, conferences and presentations in a manner which allows them to be easily reported to commissioners and managers. This type of data usually proves helpful for service review and improvement, commissioning conversations and funding oversight.

Many teams devise their own spreadsheets, but the Parent-Infant Foundation also offers a free data portal system to record anonymised family descriptors (age at referral, ethnicity, etc.), clinical outcomes and non-clinical outputs. It is helpful to have a very clear protocol for who collects, enters and analyses each kind of data as learning from other teams is that there is often an assumption it is someone else’s job.

We may be able to provide you with aggregated anonymised data from other parts of the country to help you benchmark your own activities and support your quality improvement work. Please see Chapter 8 Managing Data and Measuring Outcomes or contact us for further details.

Steady-state management and expansion

Listening to the experienced team developers we have spoken to, it can take a specialised, multi-disciplinary team around three years to get into their full stride and start to embed their work across the system. Throughout this forming and storming stage, it is important to manage expectations of funders. Outcomes and outputs will be building but will likely not be fully representative of the maximum capability of the team.

Once a new team is stable in its core delivery, expansion into specialised areas such as the neonatal unit or parents in prison might act as a spring board for new work to be commissioned. Teams might look to take on additional roles, such as keyworkers, adult therapists or social workers.

Rapid expansion, for example rolling out a localised service across a much broader area, can put pressure on the infrastructure that supports a team, and therefore should be planned carefully.

If possible, it can be helpful if someone in the team or commissioning network can be scanning for funding opportunities, for example, charitable grants, and commissioning deadlines. Where teams have operational leads, this would usually fall to them. Public sector budgets are often being developed from September/October for the following year, so teams might need to be developing proposals over the summer.

Downloads

Footnotes

[1] The Wave Trust. Conception to Two: Age of Opportunity (2013), page 89 https://www.wavetrust.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=474485e9-c019-475e-ad32-cf2d5ca085b0

[2] Early Intervention Foundation (2018). Realising the Potential of Early Intervention p.6. https://www.eif.org.uk/report/realising-the-potential-of-early-intervention

[3] Danny Taggert (June 2018). Trauma-informed responses in relationship-based practice. Research in Practice. https://www.rip.org.uk/news-and-views/blog/trauma-informed-responses-in-relationship-based-practice/

[4] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infographic: 6 Guiding Principles To A Trauma-Informed Approach https://www.cdc.gov/cpr/infographics/6_principles_trauma_info.htm

[5] Sweeney A, Clement S, Filson B & Kennedy A (2016). Trauma-informed mental healthcare in the UK: what is it and how can we further its development? Mental Health Review Journal 21(3): 174-192. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/MHRJ-01-2015-0006/full/html

[6] Dalzell, K. Garland, L. Bear, H. Wolpert, M. (2018). In search of an ending: Managing treatment closure in challenging circumstances in child mental health services. London: CAMHS Press. https://www.annafreud.org/media/6593/in-search-of-an-ending-report.pdf

[7] HM Government (2018). Information Sharing: Advice for practitioners providing safeguarding services to children, young people, parents and carers. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/721581/ Information_sharing_advice_practitioners_safeguarding_services.pdf

[8] NHS England (2018). Confidentiality Policy https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/confidentiality-policy-v4.pdf

This chapter is subject to the legal disclaimers as outlined here.

This chapter is correct at the time of publication, 1st October 2019, and is due for review on 1st January 2021.